_1.jpg)

Calligraphy

Calligraphy

Iranian calligraphy is a branch of Islamic calligraphy and a significant aspect of Iranian civilization, influencing regions such as Central Asia, Afghanistan, and the Indian subcontinent. While Iranians played a central role in transforming ordinary writing into artistic calligraphy, they gradually developed their own distinct styles and techniques. Although these innovative methods have become popular in other Islamic countries, they remain closely associated with Iran.

Qazvin has been recognized as the "Capital of Calligraphy of Iran" by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance and the High Council of Culture, due to the city’s historical role in training many great calligraphers. Apart from the Permanent Museum of Calligraphy in the Chehelsotoun Palace, Qazvin hosts major annual calligraphy events, including the Iranian Calligraphy Biennial, the Quranic Calligraphy Festival, and the Ghadir Calligraphy Festival.

The Iranian Calligraphers Association was initially established in 1329 SH as free calligraphy classes. It officially received its founding letter on September 10, 1967, and gradually expanded, particularly after the 1978 Islamic Revolution, gaining popularity among youth and various social groups. Today, the Association has branches in most cities of Iran and some other countries, training many students and promoting the art of calligraphy worldwide.

| Name | Calligraphy |

| Country | Iran |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Persian Calligraphy

Persian Calligraphy

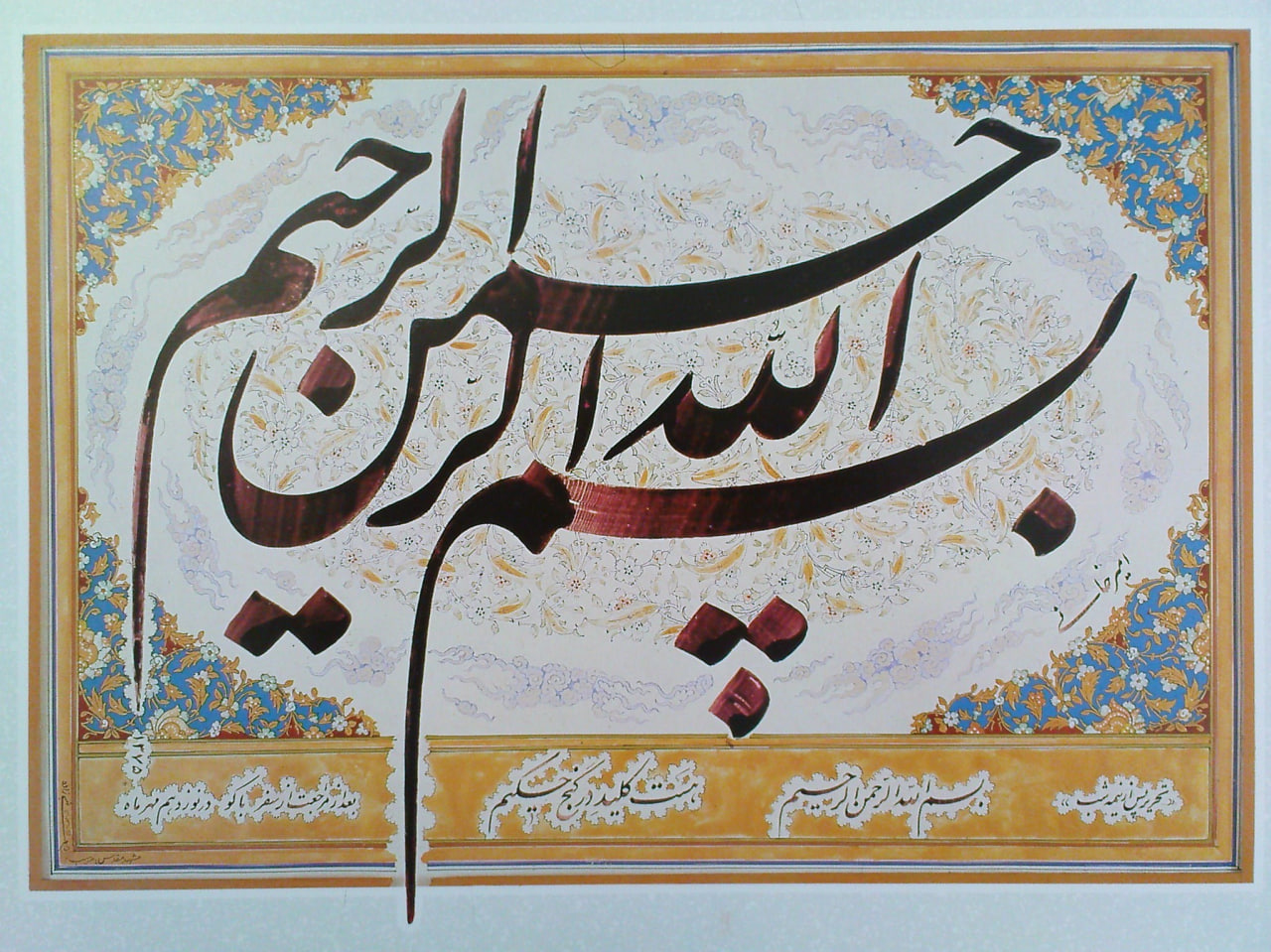

Following the advent of Islam in Iran, calligraphy was one of the Iranian arts that expanded and developed dramatically and was used in writing the Holy Qur’an and books. Muslim Iranians believed that, being the words of God Almighty, the Holy Qur’an, should be written in the best possible handwriting and, therefore, the main use of calligraphy was in writing this holy book. Despite the fact that different genres of calligraphy have appeared in Islamic lands, the role of Iranians in the development of this art has been much more outstanding.

Using calligraphy in decorating architectural works was also one of the factors that both helped develop this art and caused the formation of astounding architectural works.

History of Persian Calligraphy

According to the legends and the narrations included in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, the demons taught the art of calligraphy to Tahmuras (the mythological king of Iran) in exchange for being freed from his prison.

However, according to available historical evidence, Ali ibn Abi Talib, the first Shiite imam (7th century AD) had, during his rule in Kufa, invented a special style of writing, which was called “Kufic”. This style of writing gradually became popular throughout the Islamic territories and inspired by the Kufic script, the art of calligraphy began in the following years.

Apart from being used for writing books and decorating architectural works, calligraphy was also used for decorating pottery works, metal works, and silk and velvet clothes. It, however, seems that the use of calligraphy on silver and gold coins and agate seals was among the first uses of this art in cases other than writing books.

About 400 years after Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib (AS), the Samanids (819 to 1004 AD) popularized a new style of Kufic calligraphy. This style of calligraphy was inspired by the decorations used in architecture. Thus, it can be claimed that one factor for the popularization of calligraphic works was the inscriptions that were used in architectural monuments, which were written in Kufic, Thulth, and Naskh scripts.

The Evolution of Persian Calligraphy

Many calligraphy masters have contributed to the evolution of this art. Around the 16th century AD, a calligraphy master in Shiraz created six different styles of Kufic script. About 100 years later, certain rules and regulations for teaching and writing different alphabetic letters were outlined and a script called “Reyhan” was developed by Iranian calligraphers. Calligraphy masters trained many students from different parts of Islamic land. One of these people decorated a large number of buildings in Iraq using the art of Persian calligraphy and wrote 33 copies of the Holy Qur’an during the 13th and 14th centuries AD. A number of these old versions can be found in the museums of Iran and Europe.

Some of the great Iranian calligraphy masters include Mir Emad Hassani Qazvini (1554 to 1615 AD) - who was so skilled in calligraphy that today good calligraphy is called “Mir calligraphy” - and Gholamhossein Amirkhani (born in 1940 AD) who is considered the greatest contemporary master of Persian calligraphy.

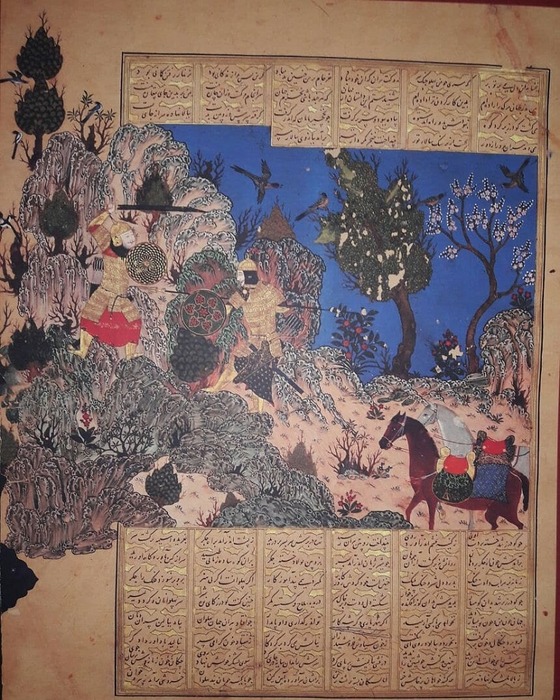

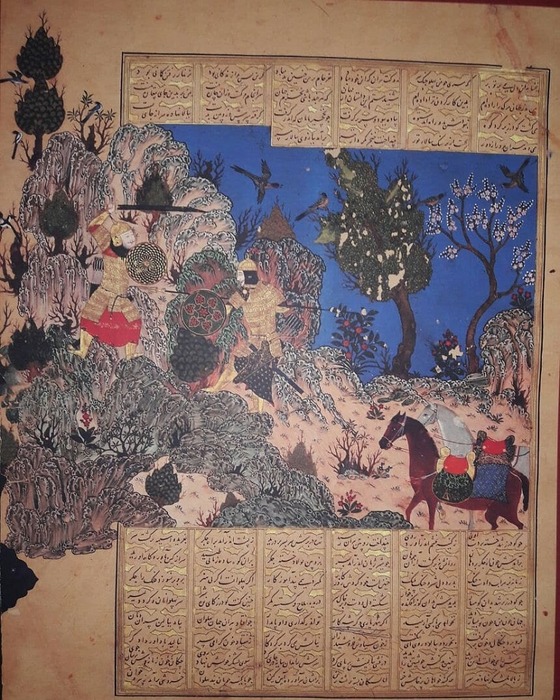

Evolution of Persian Calligraphy During the Reign of Different Governments

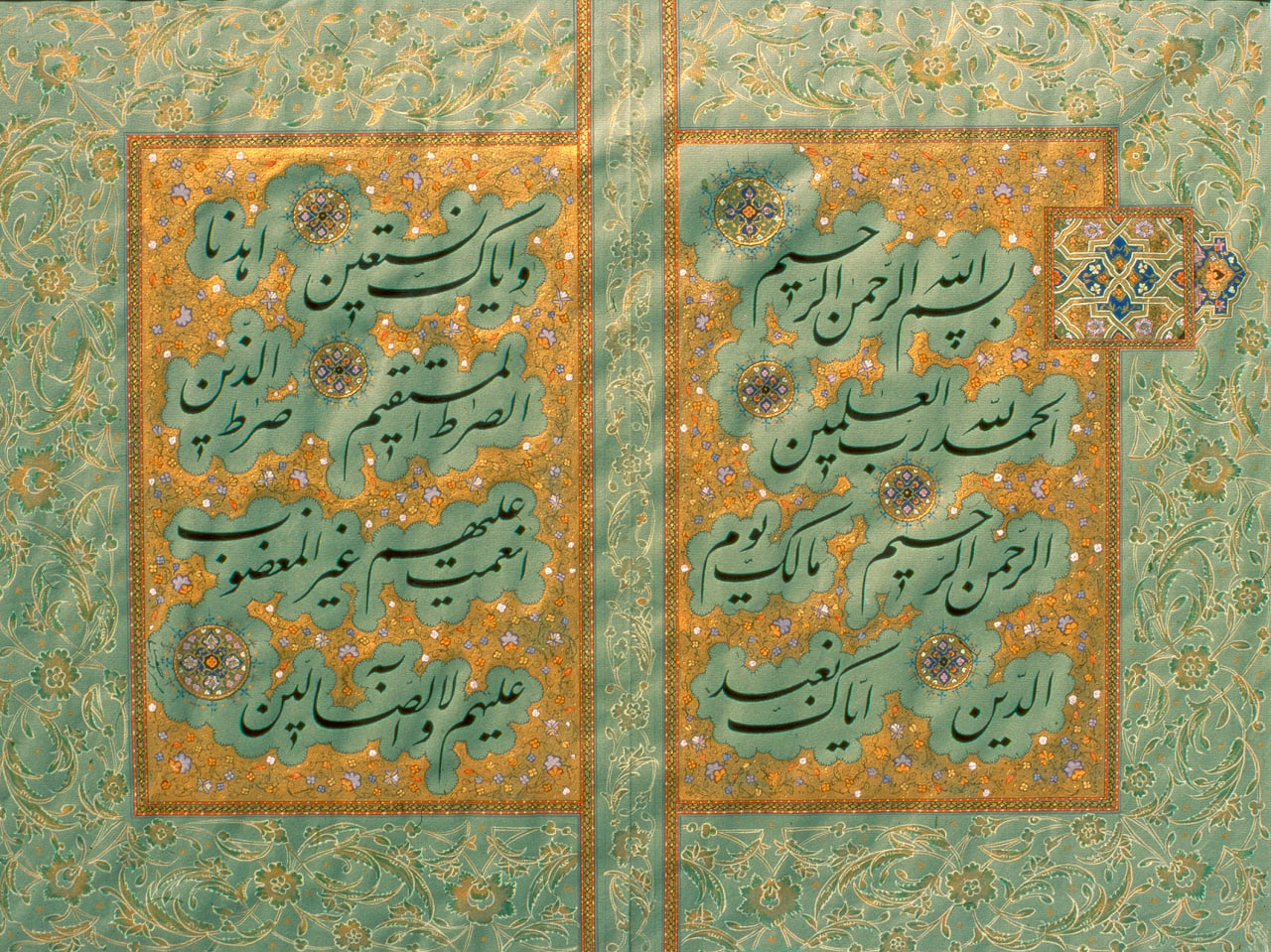

During the reign of the Ilkhanate (1256 to 1356 AD), even though it was of Mongol origin, calligraphy became very popular. One of the most beautiful works left from this period is a 65 x 54 cm copy of the Holy Qur’an whose letters are written with gold. The Timurid (1370 to 1506 AD), too, strongly supported the art of calligraphy, and a number of non-religious books such as the famous Baysunghur Shahnameh were scripted during this period.

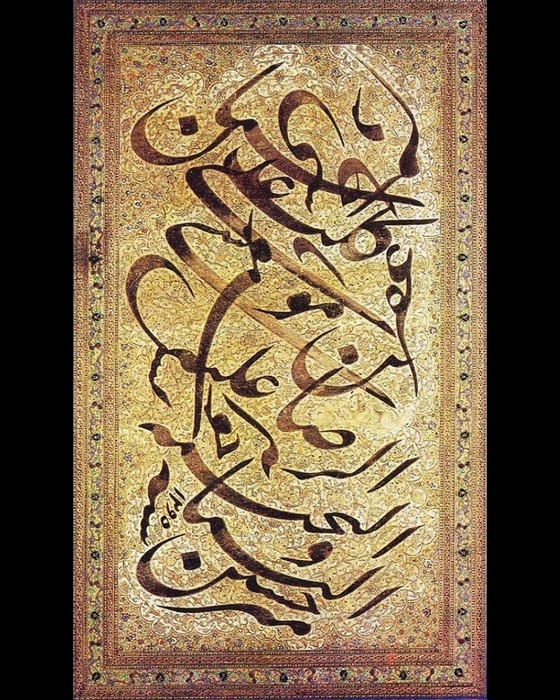

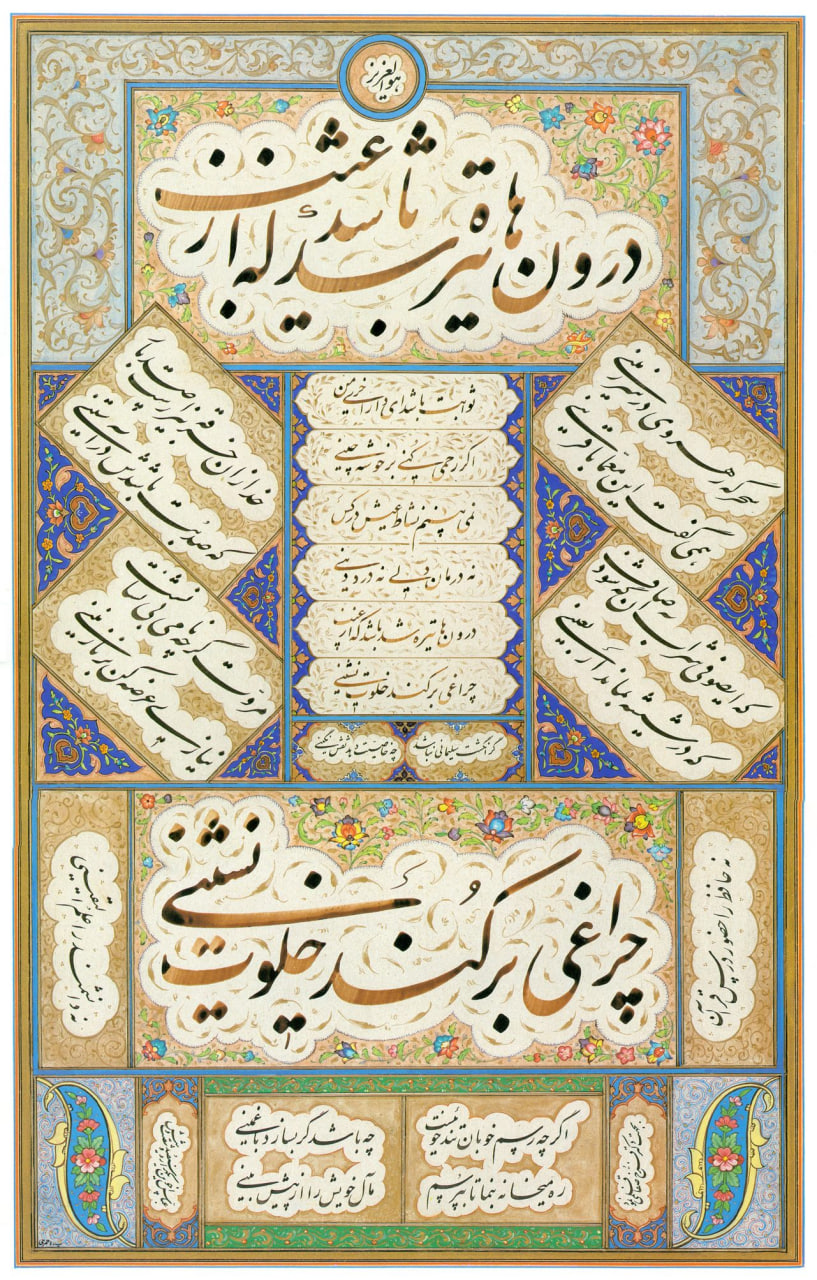

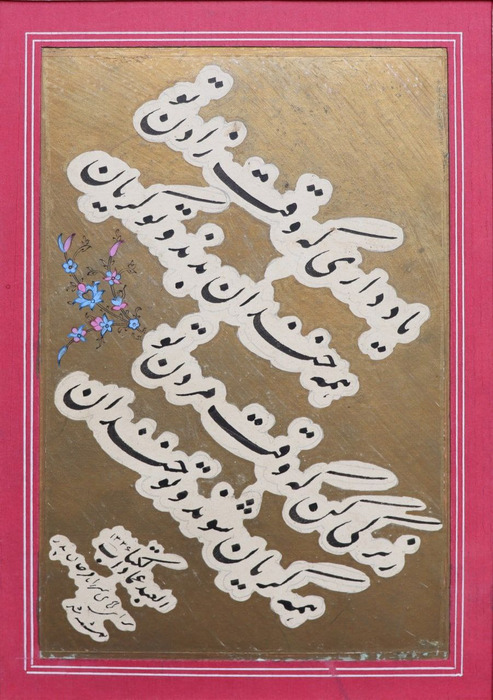

A new style of calligraphy, which became known as “Ta’liq” (meaning suspended) was created during the Timurid era and thereafter the Nastaliq script was created by combining two styles of “Naskh” and “Ta’liq”; a script, which according to some experts is the most beautiful style of calligraphy. Despite the fact that since the creation of Nastaliq, many artists tried to remove it by introducing new writing styles, this script remained quite popular and it is now considered the most popular and beautiful Persian script among Iranian calligraphers.

The interest of the Safavids (1501 to 1736 AD) in this art strengthened its growing trend and caused the emergence of several renowned calligraphy masters like Mir Emad Qazvini - one of the most famous masters of Nastaliq style of calligraphy, who scripted several works, including Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh and Jami’s poems.

Persian Calligraphy in Other Countries

Apart from Iran, the Nastaliq script found its way to Türkiye and India and many people got interested in it. A style of Nastaliq calligraphy called “Shekasteh” (lit. broken) became popular in India.

Stages of Innovation in Persian Calligraphy

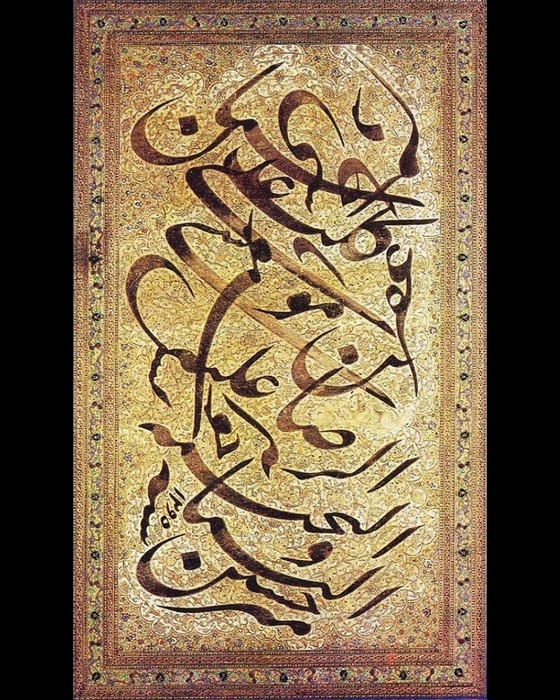

In the 16th century AD, a new art was inspired by calligraphy, which became known as “Qatai” or “Kaghazabori”. The product of this work of art was a combination of calligraphy, gold leaf, border decoration, etc. Later on, miniature, floral, and arabesque designs were also used to decorate Nashq and Nastaliq scripts and became known as the “Golzar” style.

Another style that developed with the help of calligraphy was “Masvadeh” (meaning draft). This style was born from the creative combination of different designs and styles. The use of calligraphy on coins, seals, clothes, and paintings was one of the steps that helped the progress of calligraphy.

What has strengthened the art of Persian calligraphy is the rich Iranian literature and in spite of the expansion of the printing industry calligraphy continues to be popular art in Iran.

The art of Persian calligraphy was inscribed on the list of UNESCO as an intangible world heritage in the year 2022.

Persian calligraphy or Iranian calligraphy is one of the most revered arts of Iran, which has gradually evolved and many calligraphers have contributed to different genres of this art. Nastaliq is an outstanding genre of Persian calligraphy that has come to be known as the most beautiful human calligraphy.

| Name | Persian Calligraphy |

| Country | Iran |

| Type | Calligraphy |

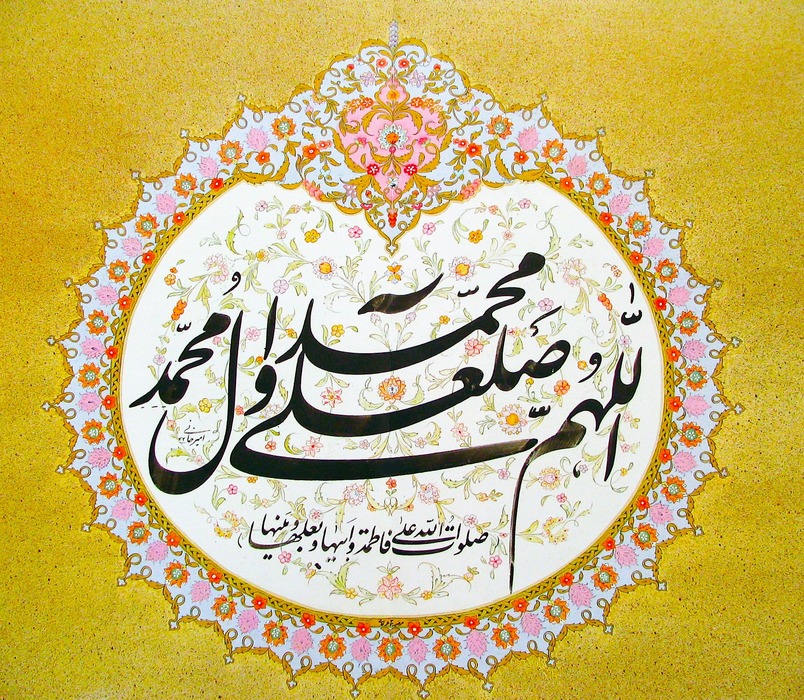

Calligraphy; the Gem of Islamic-Iranian Art

Calligraphy; the Gem of Islamic-Iranian Art

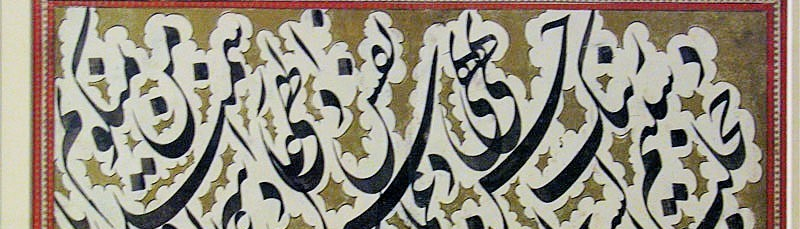

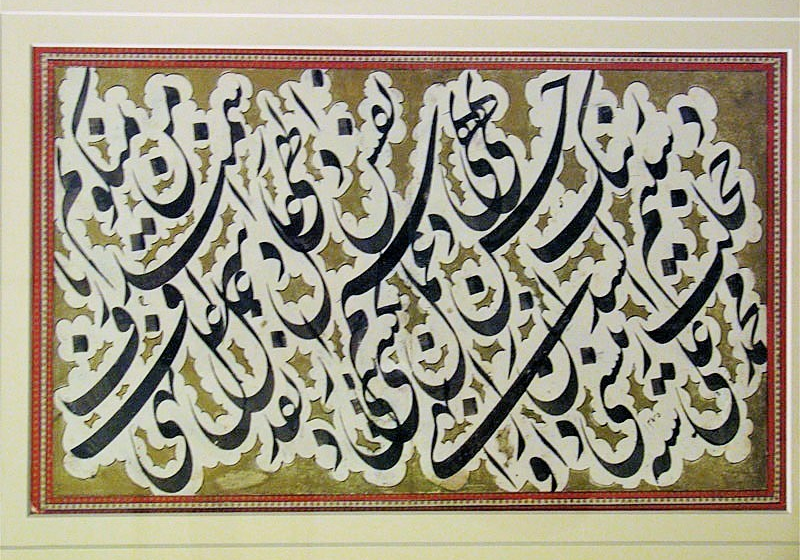

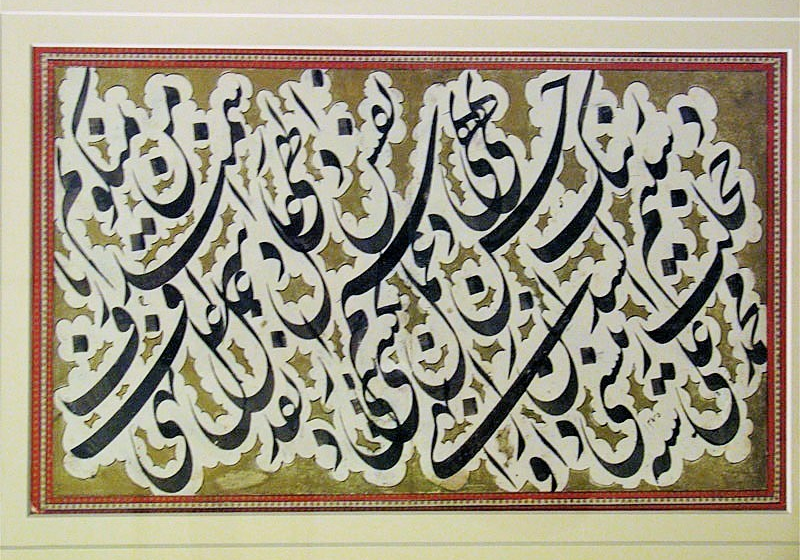

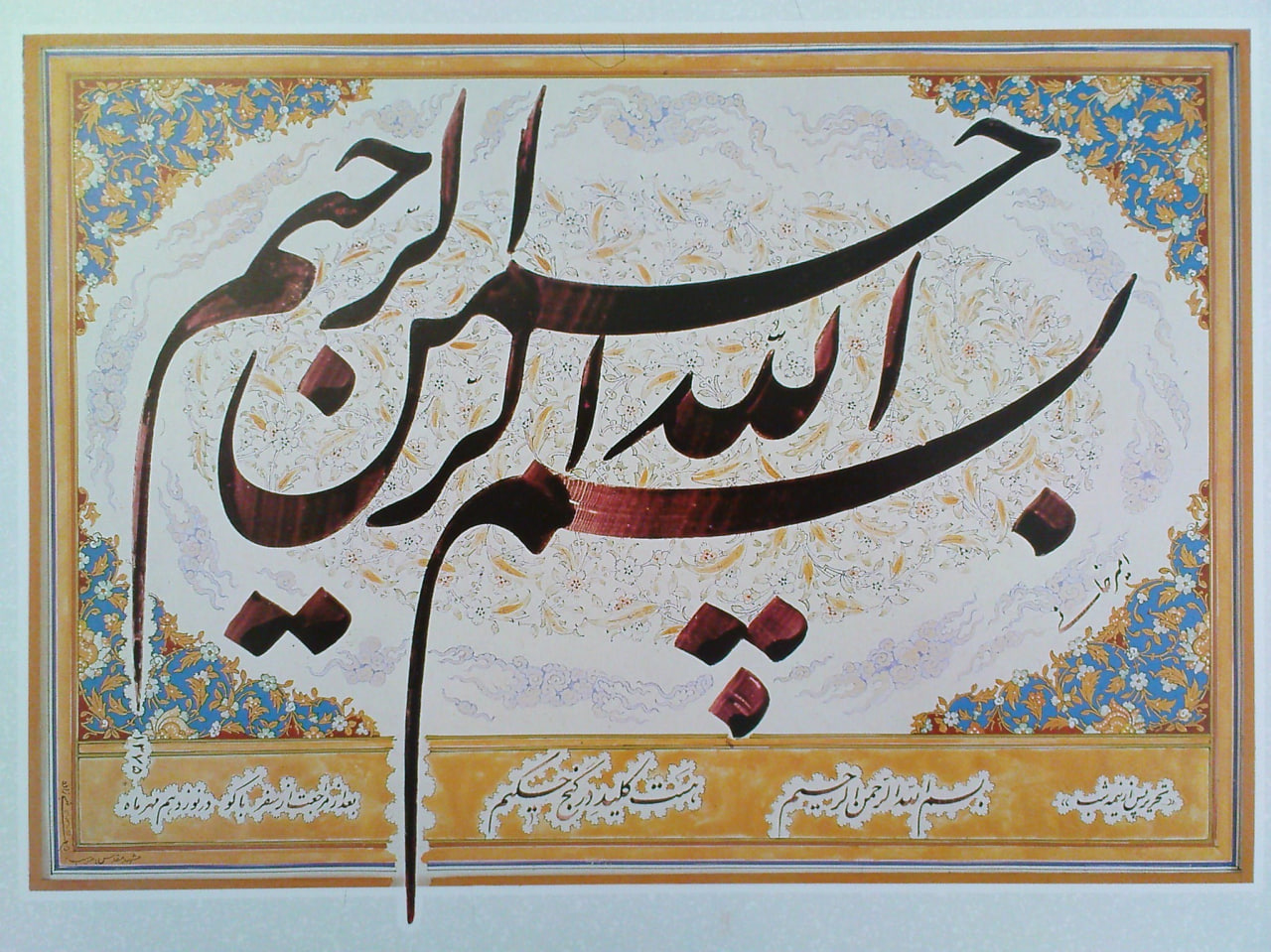

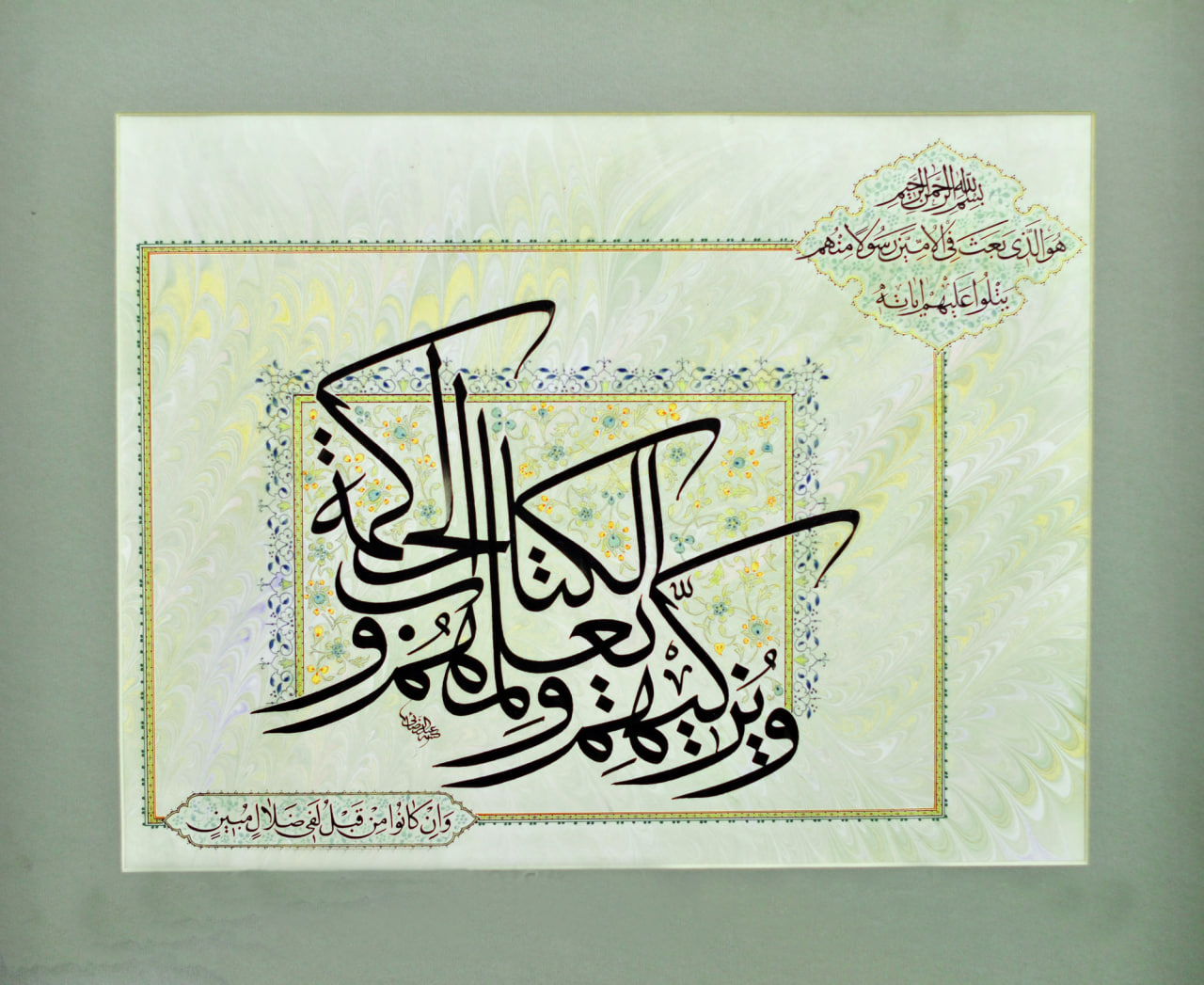

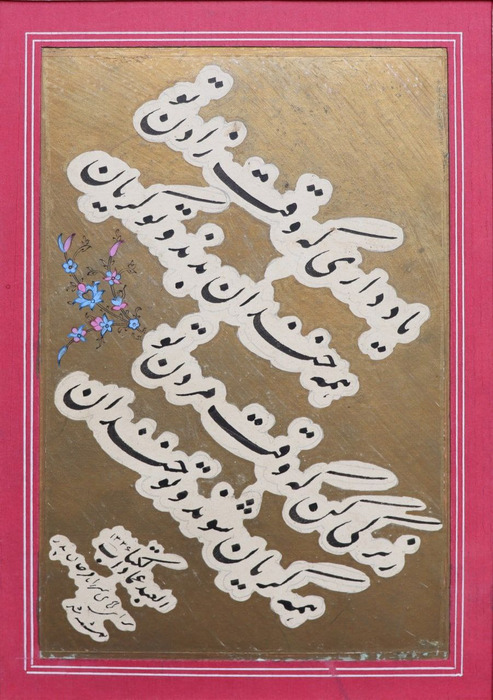

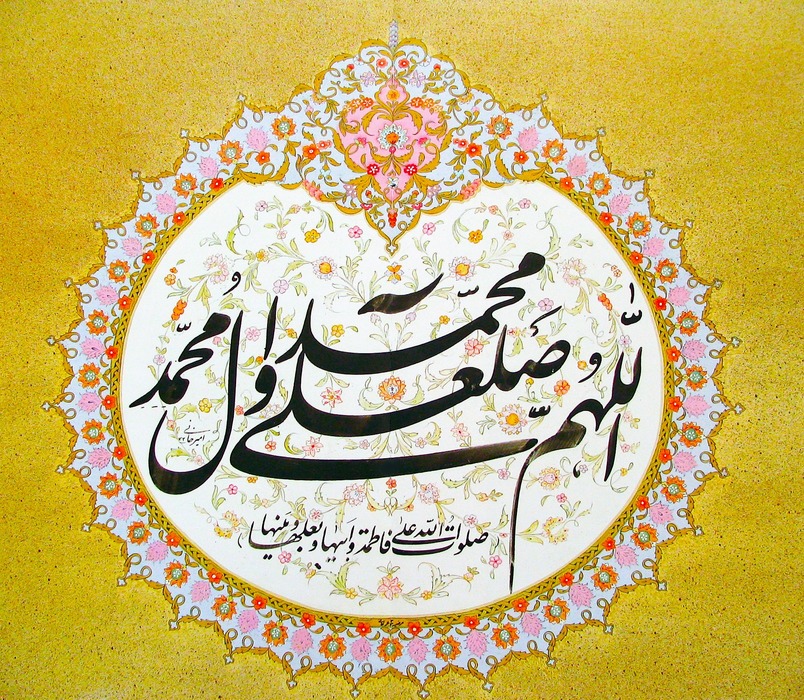

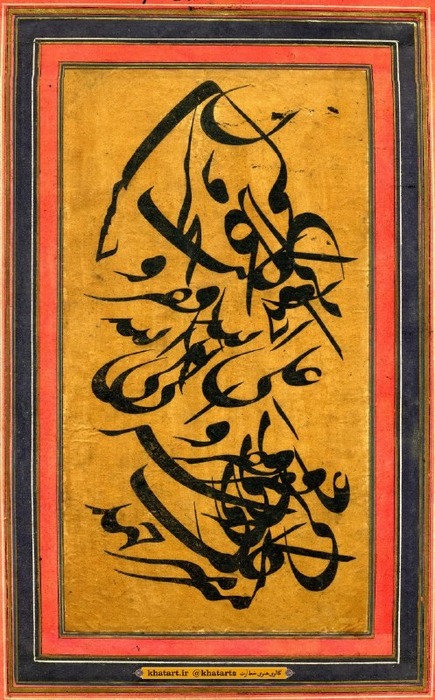

Calligraphy in Nastaliq Script, by Gholamhossein Amirkhani

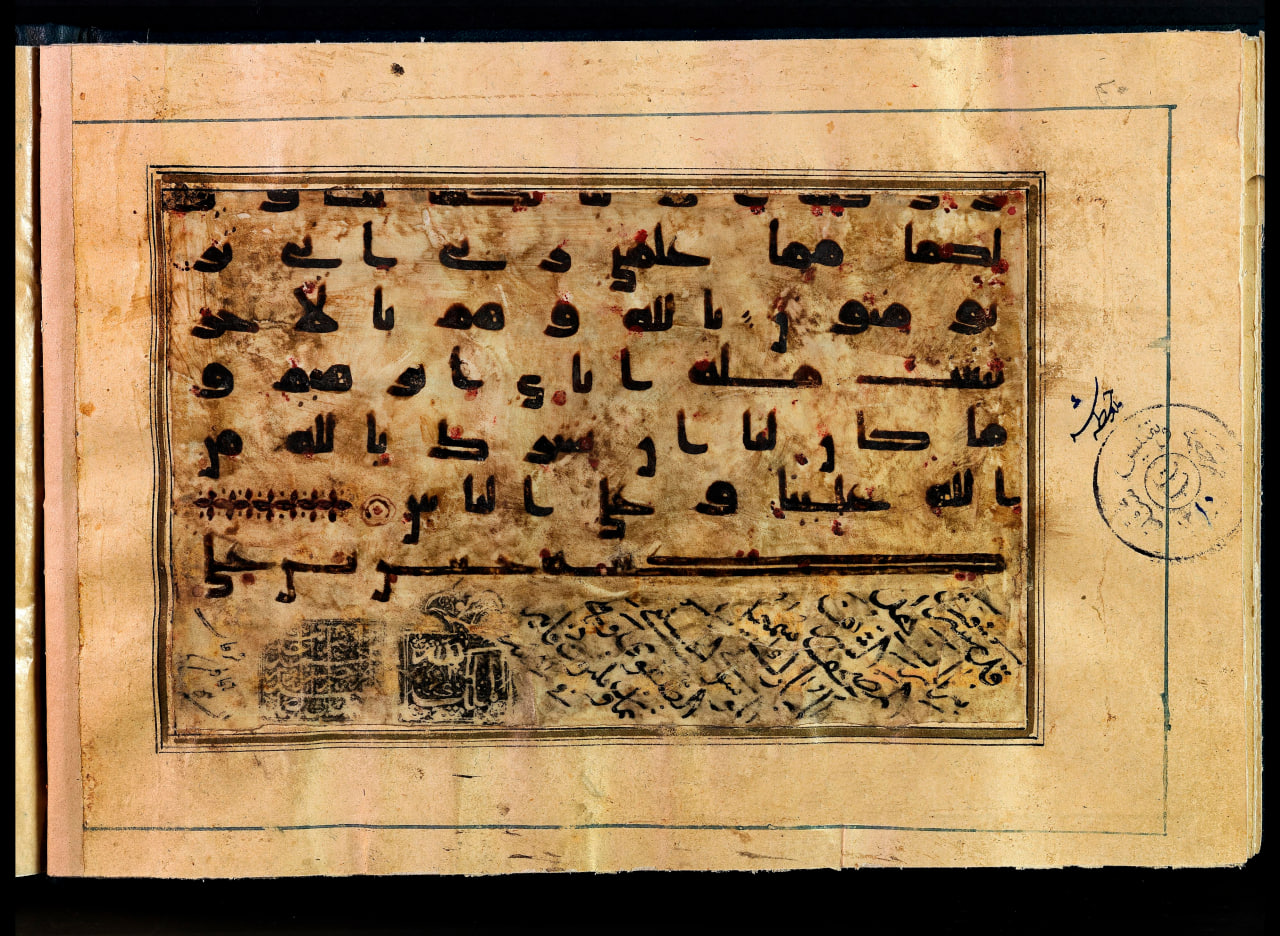

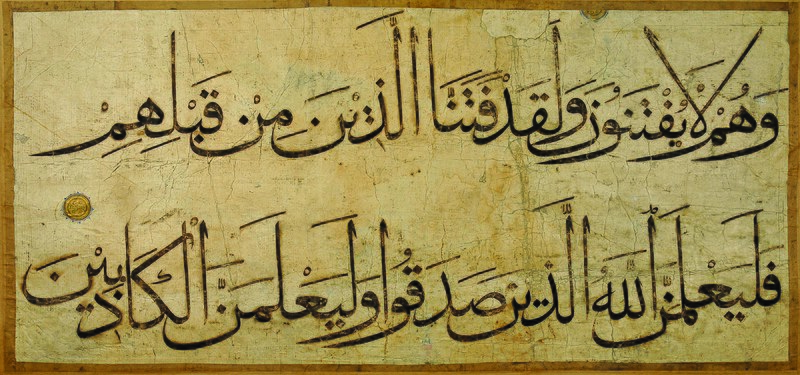

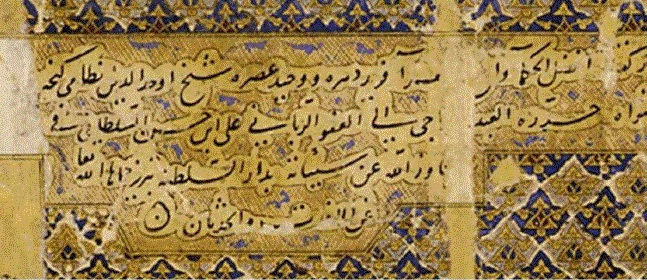

A Qur’an manuscript in Kufic script, attributed to Imam Hasan al-Mujtaba (peace be upon him), preserved in the treasury of the National Library and Museum of Malek.

.

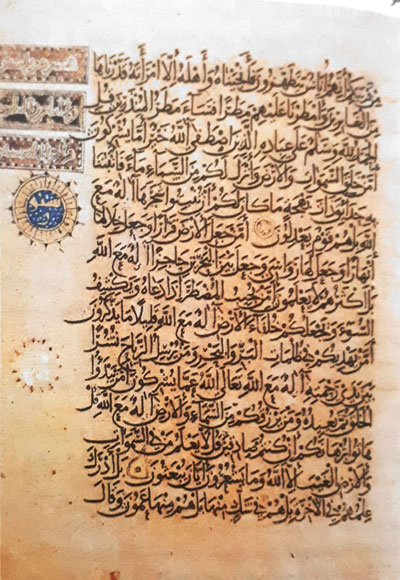

A page from the Qur’an in Naskh script, written with Ibn al-Bawwab’s pen.

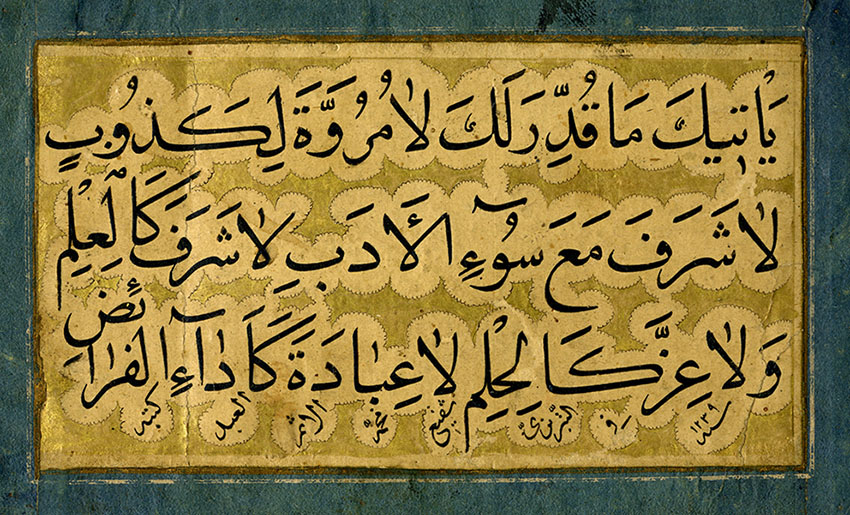

Calligraphy in Naskh Script

By Mohammad Shafiʿ Tabrizi

Calligraphy in Thuluth Script

By Ahmad Abdulrazaei

Qur’an Calligraphy in Muhaqqaq Script

By Baysonqor Mirza

.jpg)

Calligraphy in Rayḥān Script By Majd al-Din Nasiri Amini

.jpg)

Calligraphy in Tawqīʿ Script By Abdullah Amāsi

Ruqʿah script was initially known primarily for single-page writings (raqʿah). In this style, the letters are thinner and the curves more rounded compared to Tawqīʿ script. Ruqʿah is mainly used for purposes such as fast writing and concise note-taking.

Calligraphy in Ruqʿah Script, by Naser Tavousi

.jpg)

Calligraphy in Taʿlīq Script

The first line is written by Hāshem Mohammad Khaṭāṭ, and the second line by Sayyid Ebrāhīm.

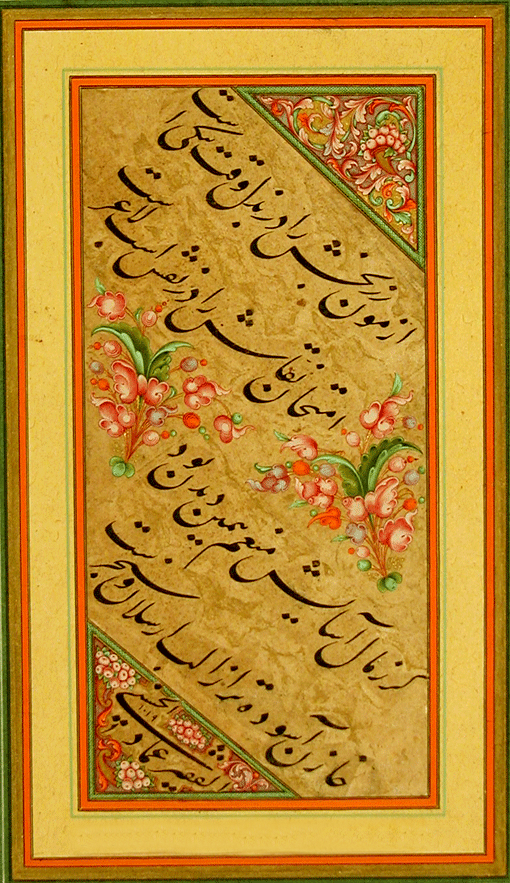

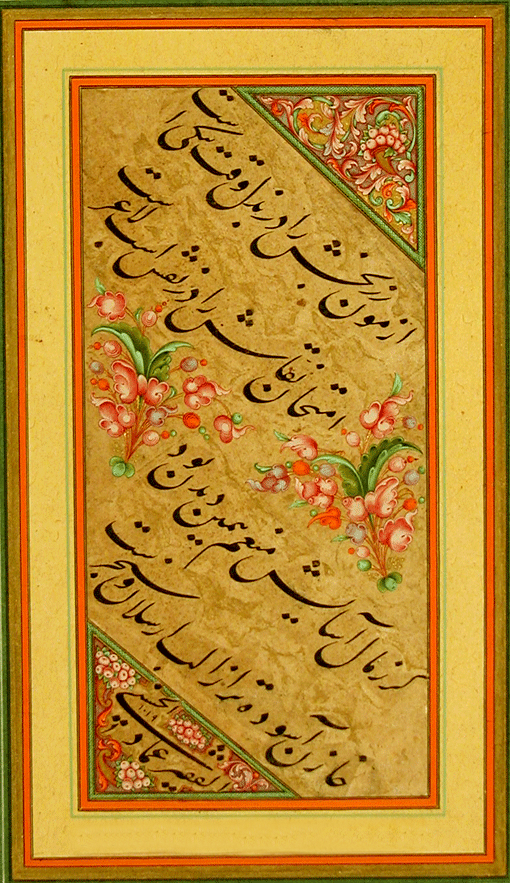

Calligraphy in Nastaʿlīq script, by Abbas Akhavan

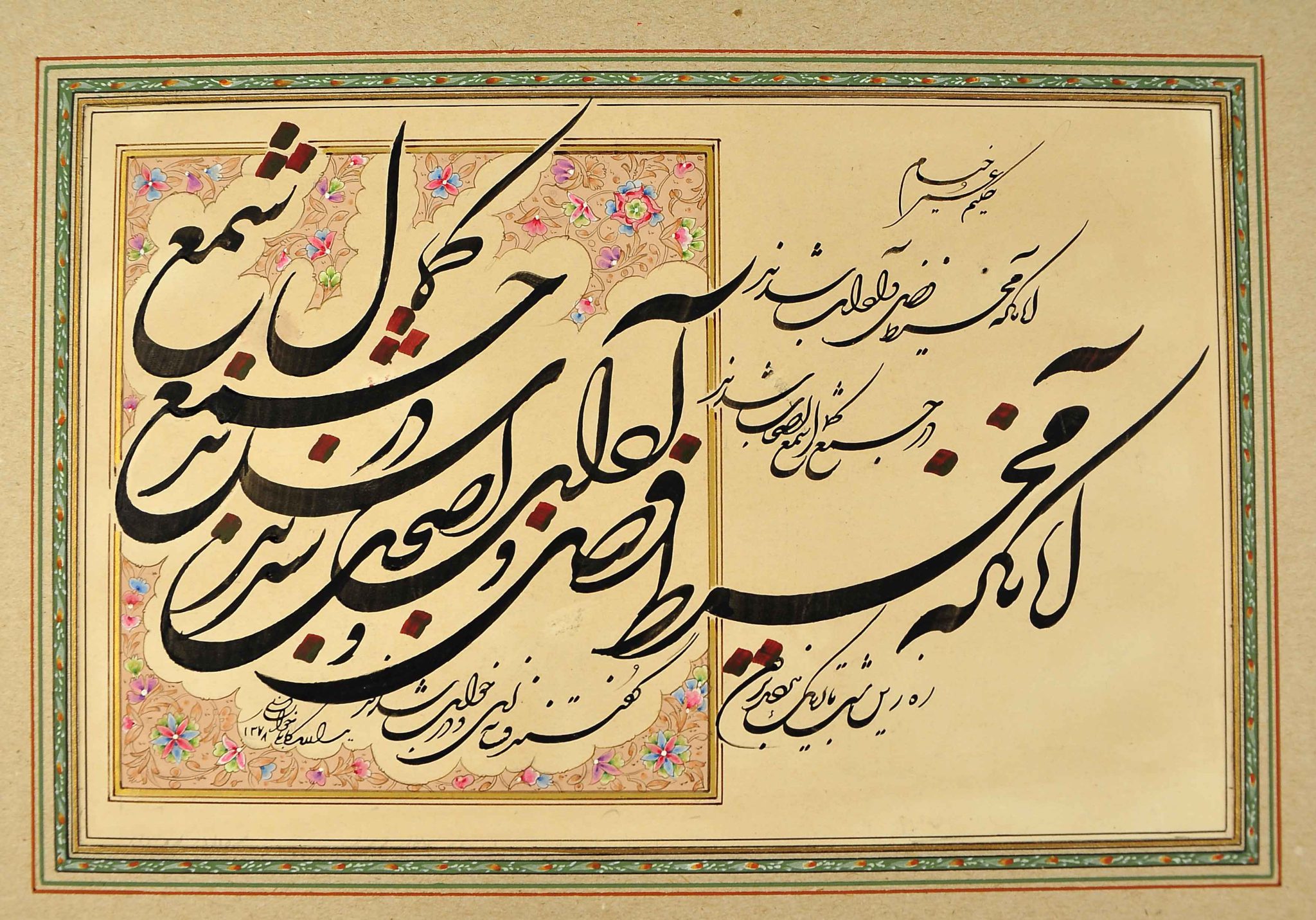

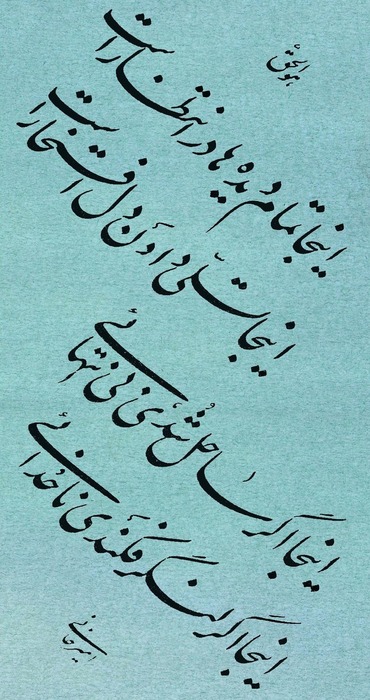

Calligraphy in Shekasteh-Nastaʿlīq Script, by Yadollah Kaboli

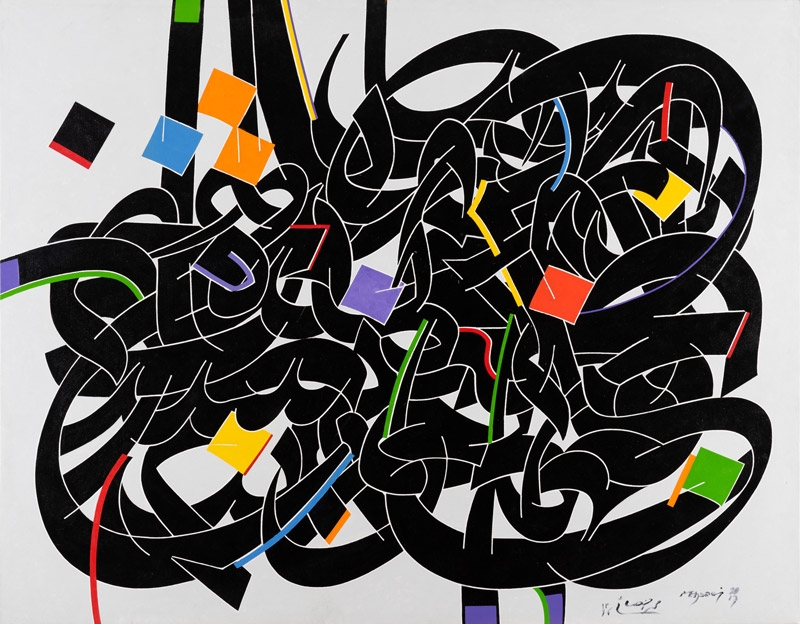

Calligraphic Painting by Mohammad Ehsai

.

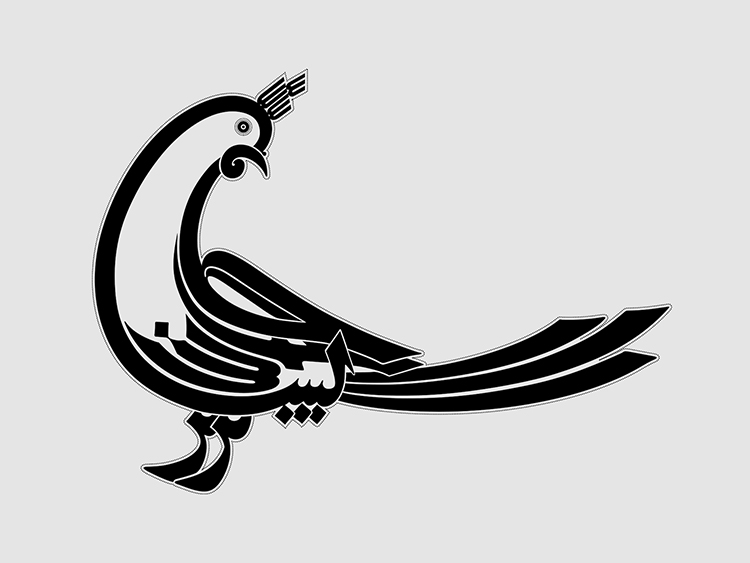

Calligraphic Painting of “Bismillah” Bird by Reza Mafi

| Name | Calligraphy; the Gem of Islamic-Iranian Art |

| Country | Iran |

| Type | Calligraphy |

| awards | International,National |

Mir Emad: The Master of Nasta‘liq Calligraphy in Iran

Mir Emad: The Master of Nasta‘liq Calligraphy in Iran

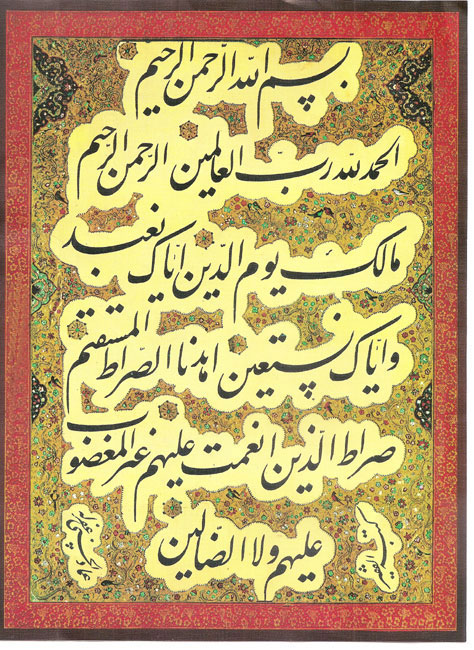

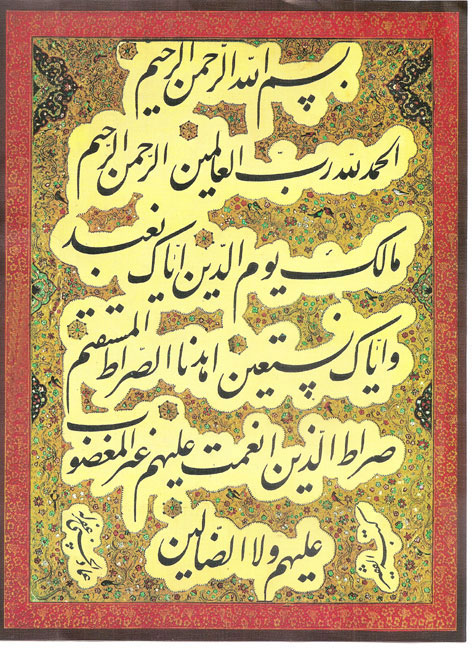

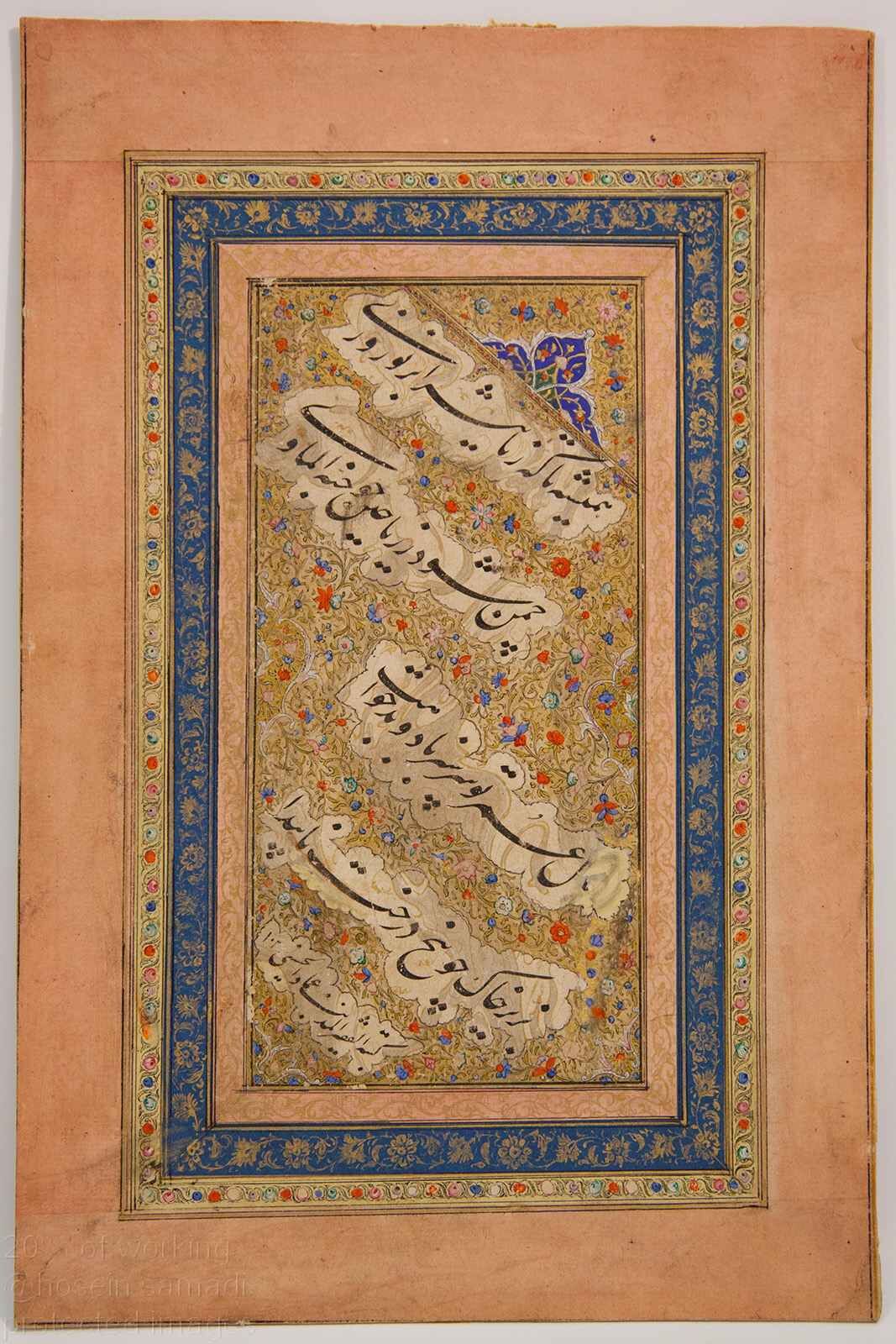

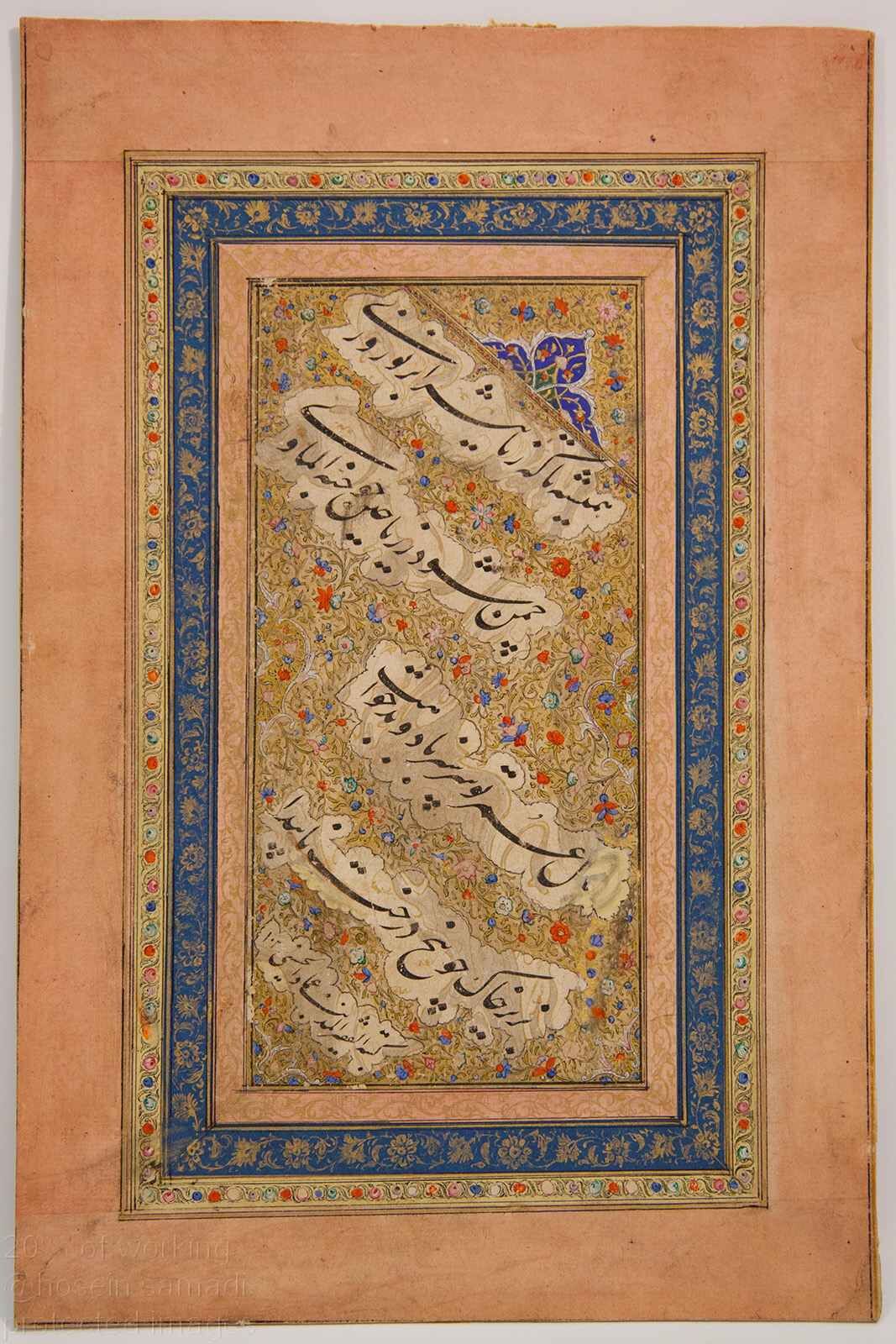

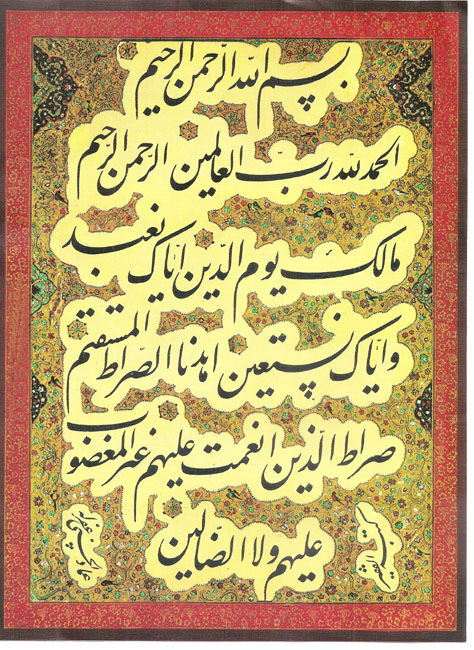

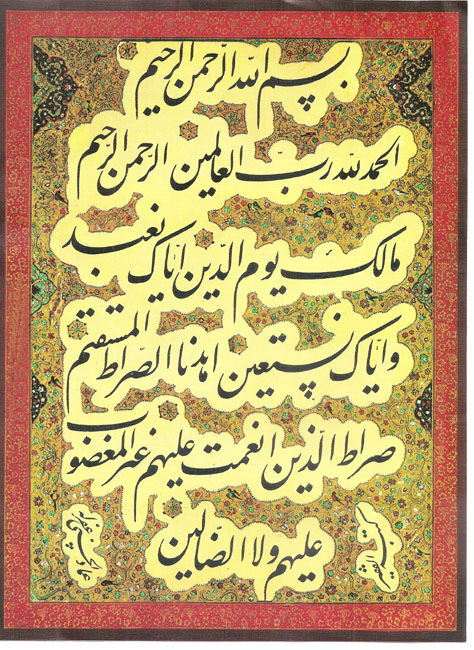

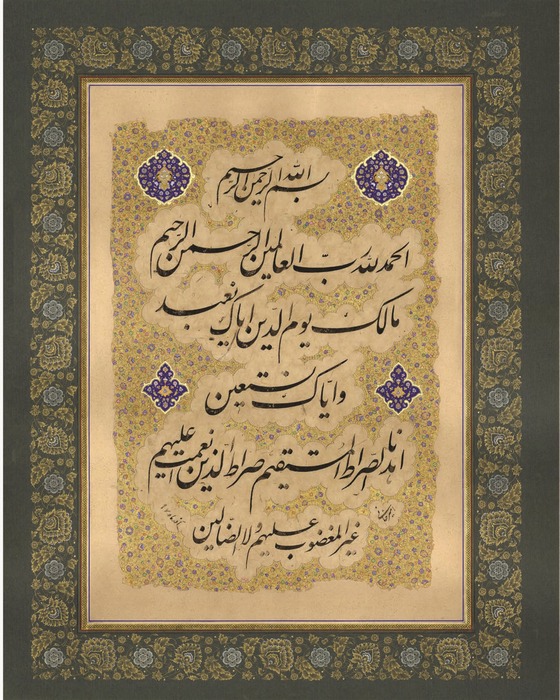

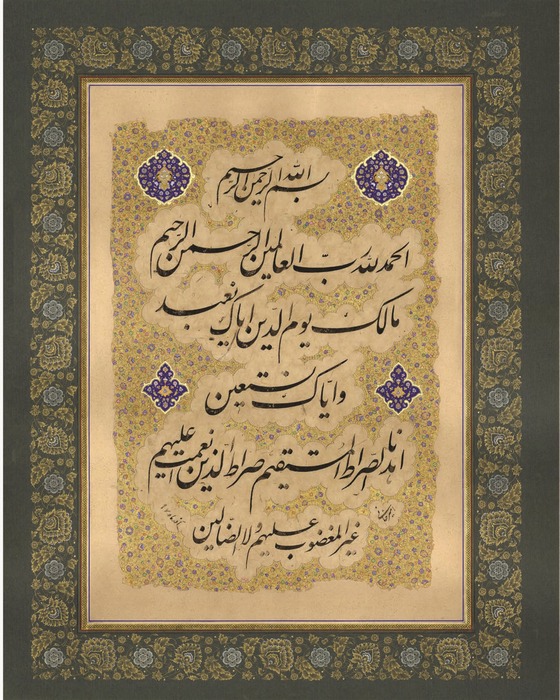

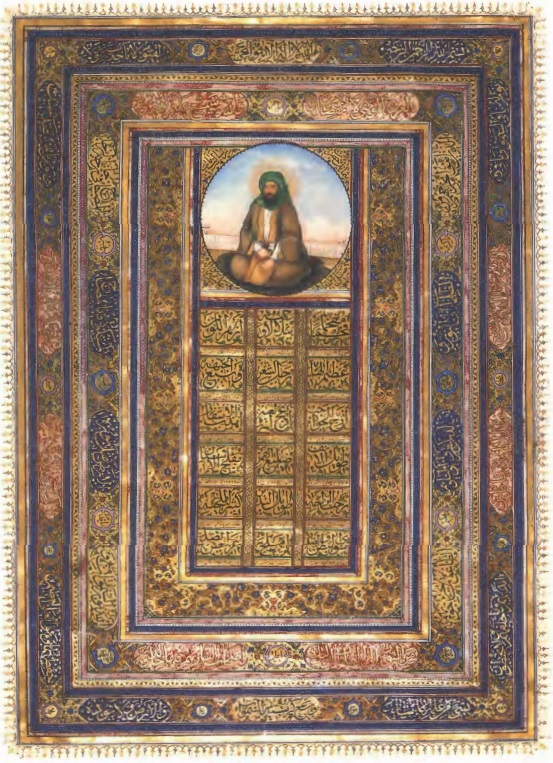

Calligraphy of Surah Al-Fatiha by Mir Emad

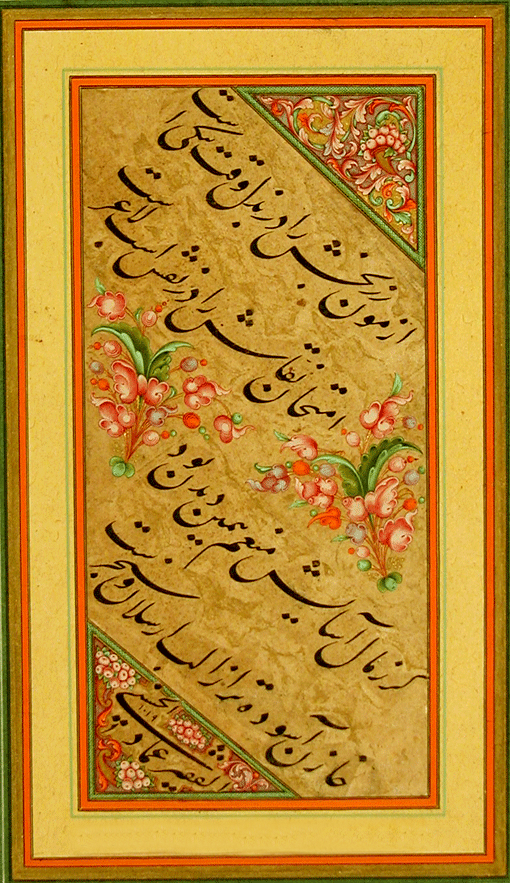

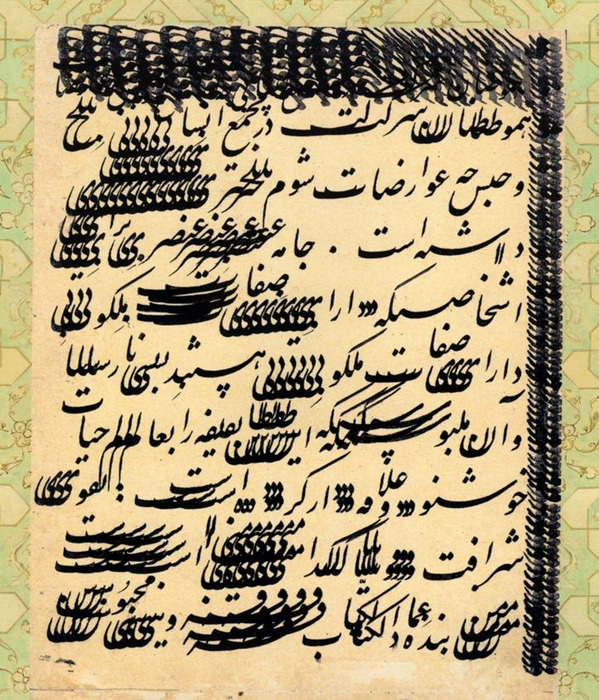

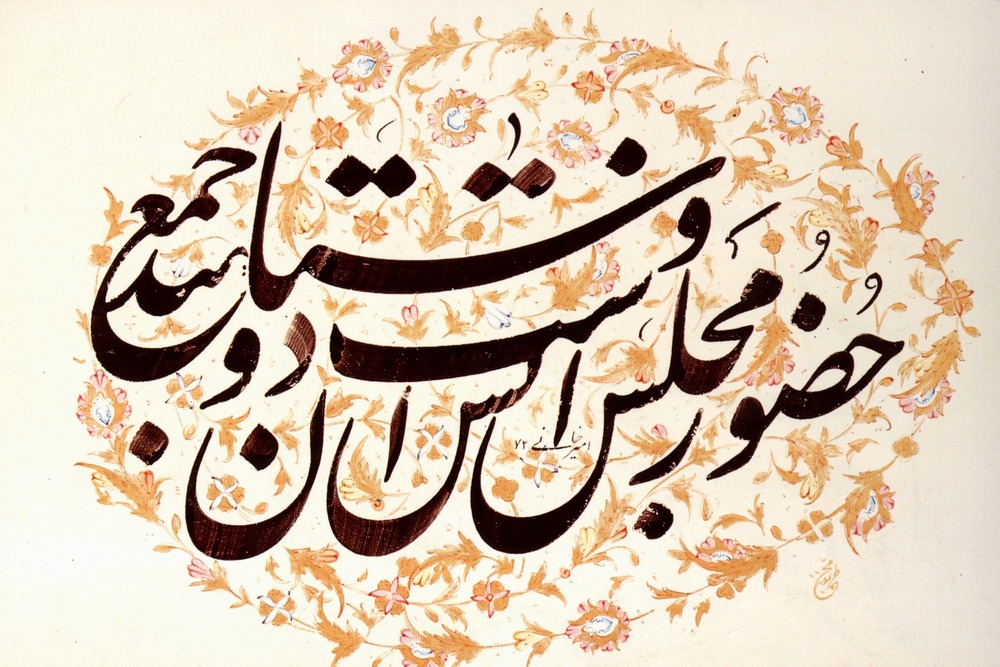

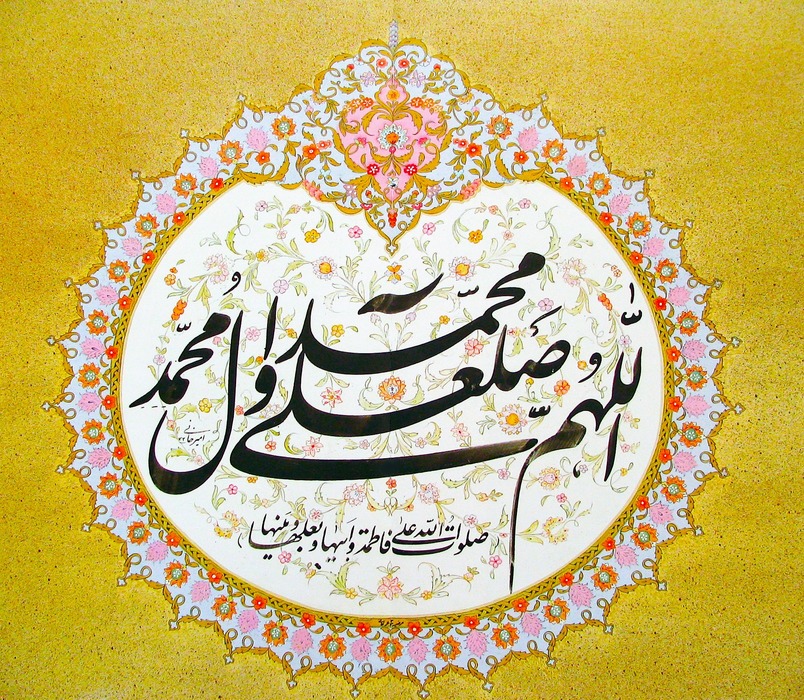

Chhelipa by Mir Emad

These include copies of classical literary and religious texts, such as: Tuhfat al-Ahrar by Jami,Divan of Hafez, Golshan-e Raz by Sheikh Mahmoud Shabestari, Golestan by Saadi,Takmela-ye Nafahat, Masnavi-ye Goy o Chogan by Arifi, Tuhfat al-Muluk, Al-Asma al-Husna, Subha al-Abrar by Jami and others.

These include instructional and literary works, such as: Nasaih, Munajat by Khaja Abdullah Ansari, Zinat al-Muluk, Munajat of Imam Ali (AS), Pandnamehof Jami for his son, Haft Band by Hossein Kashani, Rubaiyat of Khayyam, and similar texts.

Various practice sheets written with different pens and styles, often used for instruction or display of skill.

Individual or combined calligraphic panels, including collaborations with other calligraphers. The numbered pieces attributed to Mir Emad total approximately 160 items.

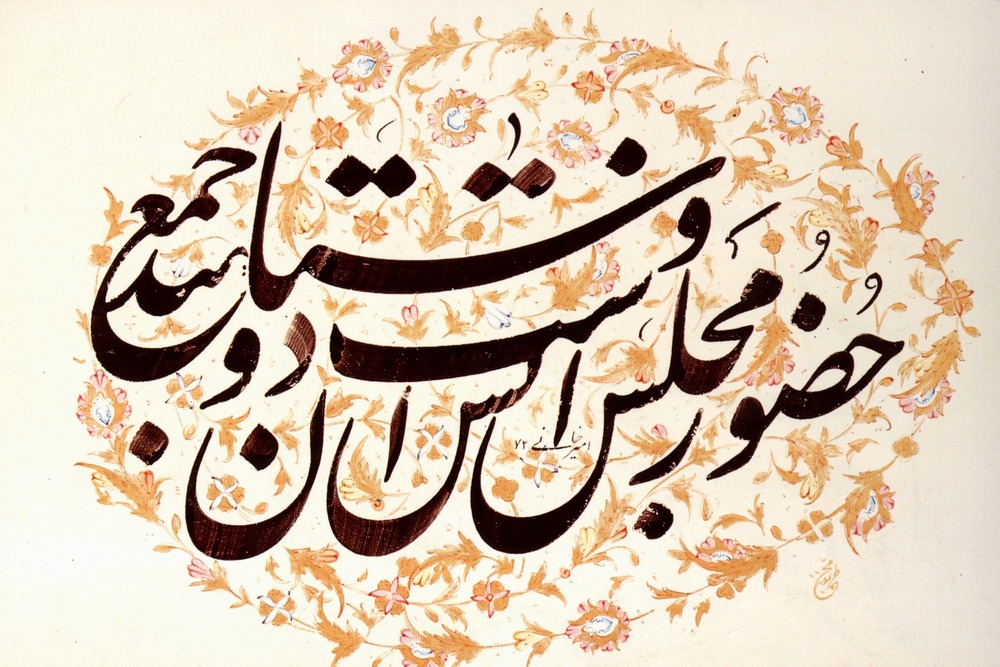

Chalipa in the Handwriting of Mir Emad

| Name | Mir Emad: The Master of Nasta‘liq Calligraphy in Iran |

| Country | Iran |

| Type | Calligraphy |

Emad al-Ketab: Reviver of Persian Calligraphy

Emad al-Ketab: Reviver of Persian Calligraphy

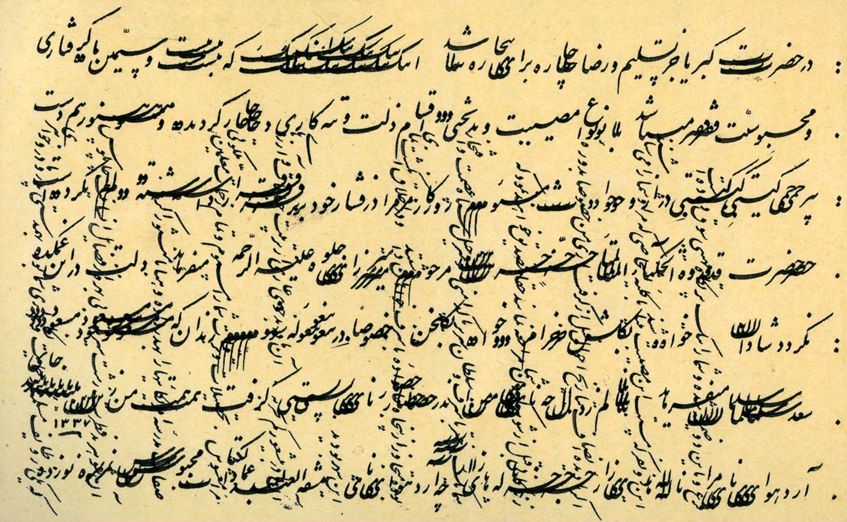

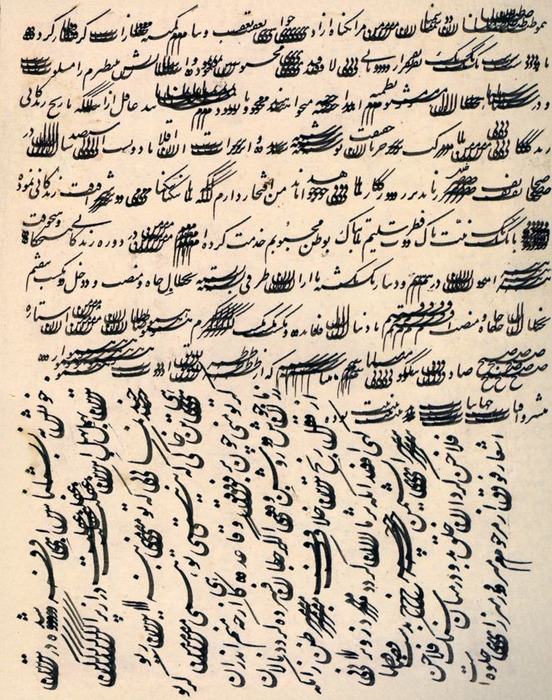

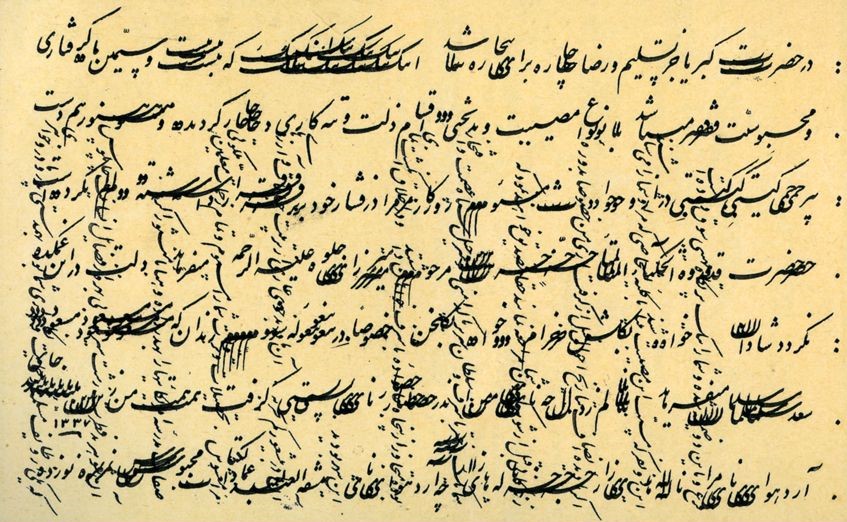

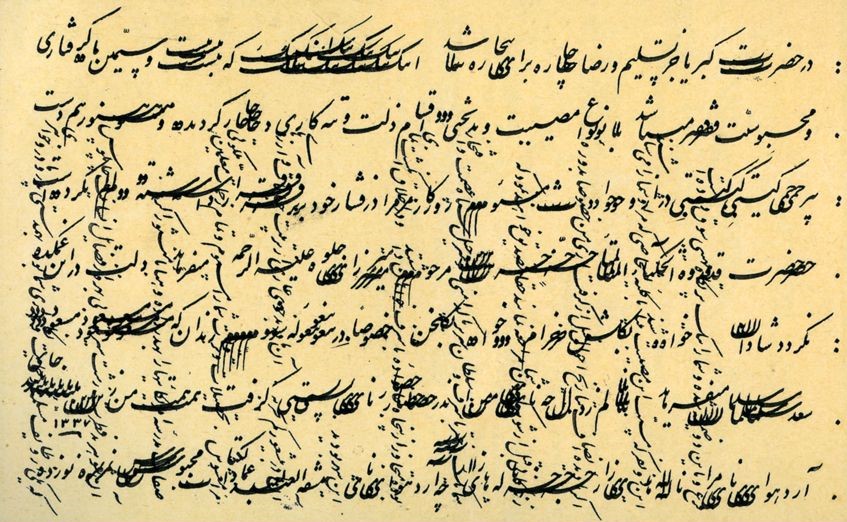

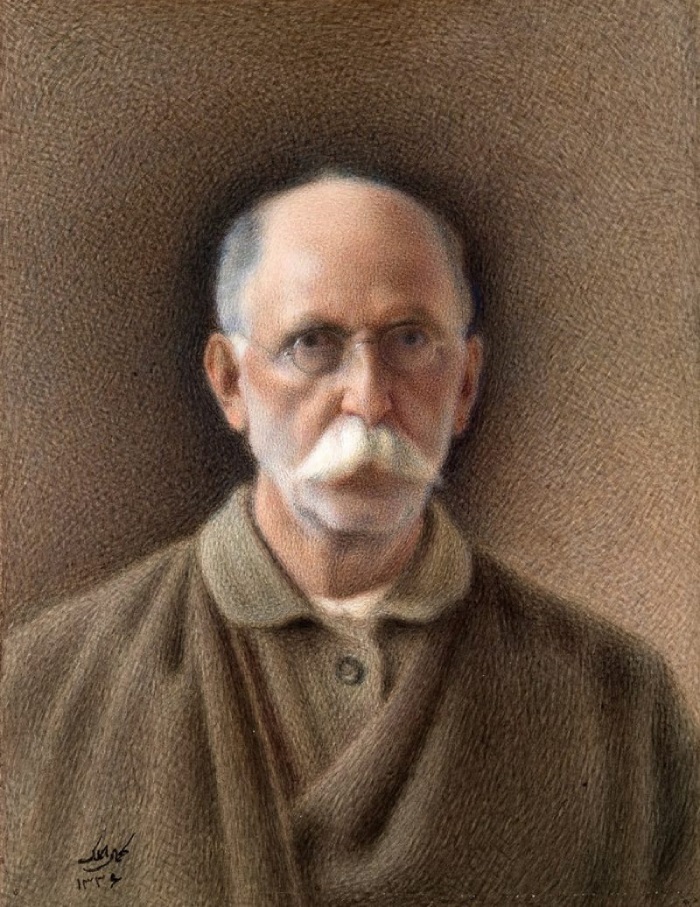

Mirza Mohammad Hossein Seyfi Qazvini, known by the title Emad al-Ketab, was born in 1240 SH (1861–1862 CE) in Qazvin, a major center of calligraphy in Iran. His father, Mirza Mohammad Qazvini, worked as a deed-writer, and with his encouragement, Mohammad Hossein became literate at the age of eight. He spent the early years of his youth studying traditional Islamic sciences, and later, driven by personal interest, he pursued modern subjects as well. In addition to the conventional knowledge of his time, he dedicated himself to learning French and completing his mastery of Arabic. Emad al-Ketab learned the fundamentals of calligraphy in Qazvin, studying under several masters, including Mirza Mohammad Ali Khoshnevis Qazvini. At the age of fourteen, he went to Rasht as an apprentice to a merchant from Shirvan. When he returned to his hometown after a year, he discovered that he had lost his father. The early remarriage of his mother added to his sorrow, and as he himself expressed, he endured much grief and loneliness during this period. At sixteen, Emad, accompanied by his younger brother, traveled to Iraq and resided in Kadhimiya for three years. These years were marked by hardship and struggle, during which he earned his living through manuscript writing. It is believed that during this period, he copied a Quran, a course in jurisprudence by Agha Seyyed Ali Bahr al-Uloom, and various other religious treatises, all written in Naskh script, which constitute the major works of this formative three-year stage. After some time, a man named Hojjat al-Islam Seyyed Mohammad Baqer found him and took him to the holy city of Karbala. Emad al-ketab spent nearly five years of his life there. At the end of the fifth year, which coincided with the late Naser al-Din Shah period and Emad’s 23rd year, he returned to his homeland. Upon his return, he founded his own calligraphy school called “Dar al-Ketabeh” on Naseriyeh (Naser Khosrow) Street in Tehran, making a living by teaching calligraphy and manuscript writing. During the reign of Mozaffar al-Din Shah, he joined the Ministry of Publications as a scribe, officially starting in year 1317 (of the Islamic calendar) as a government clerk. At the Shah’s request, Emad began copying Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, a monumental project that took three years to complete. His masterful calligraphy in this work impressed Mozaffar al-Din Shah, who honored him with the title “Emad al-Ketab”. This historical period coincided with the Constitutional Revolution in Iran. Emad al-Ketab, a man of independent spirit, supported the constitutionalists and actively participated in the movement. During the reign of Mohammad Ali Shah, due to his alignment with the constitutionalists, he was forced to flee into the mountains and deserts. Shortly afterward, in 1344 AH, he joined the Committee of Punishment and undertook the task of writing the committee’s proclamations. After the committee was exposed, Emad al-Ketab was sentenced to five years in prison. During these years, he produced many siyah-mashq (practice sheets), which often contained personal reflections and meditative writings. Emad al-Ketab was also the first Iranian calligrapher to travel to Russia, England, and Europe, and through these journeys, he was able to develop improved methods for compiling Persian calligraphy practice manuals (Rasm al-Mashq).

Artistic Style of Emad al-Ketab

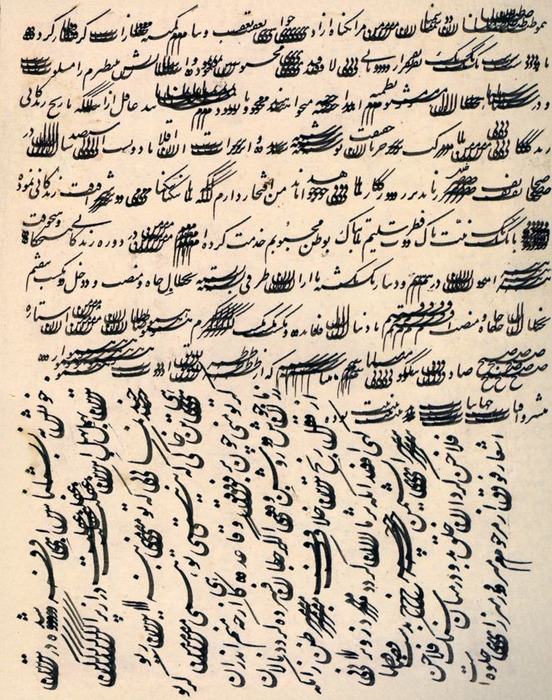

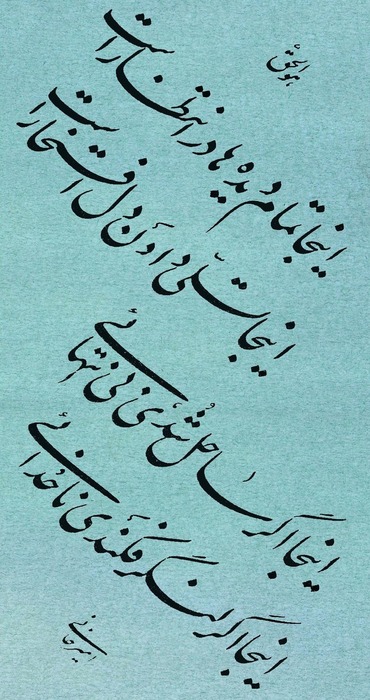

Emad al-Ketab was among the calligraphers proficient in the seven scripts and sought to master Naskh, Nastaliq, Shekasteh-Nastaliq, and Thulth, achieving notable success. Although he did not study directly under Mirza Mohammadreza Kalhor, he fully recognized the true value of Kalhor’s work and carefully analyzed the nuances and artistic subtleties of his calligraphy style. Two decades after Kalhor’s death, when his distinctive Nastaliq style was fading from memory, Emad al-Ketab began studying and practicing his works. Through this effort, he revived and elevated Kalhor’s style, ensuring its preservation and continued influence in Persian calligraphy.. A key characteristic of Emad al-Ketab’s style is the fluidity and single-stroke execution of letters and words, inspired by the technique of Mirza Kalhor. Remarkably, he achieved this without altering the fundamental skeleton and method of Kalhor’s script. Other notable traits of Emad’s calligraphy include speed of writing, precise sharpening of the pen, and smooth, even strokes of letters and words—qualities that contemporary calligraphers describe as the “rhythm of heart and hand”. Consequently, Emad’s style aligns closely with Kalhor’s, effectively complementing and completing Kalhor’s school of calligraphy.

Through meticulous study of printed works, calligraphic pieces, and black practice sheets left by Mirza Reza Kalhor, Emad discovered the secrets, rules, and artistic techniques of his predecessor, fulfilling his historical and artistic mission of propagating Kalhor’s style. By incorporating his own creative innovations, Emad merged his unique approach with Kalhor’s refined style, introducing the feature of segmentation (taqti ‘) into Nastaliq script. In addition, Emad al-Ketab was able to perfect certain strokes within the framework of Kalhor’s school. He was recognized as the first calligrapher to introduce a system of dotting (punctuation) in calligraphy instruction. Not only did he apply this technique to Nastaliq script, but he also extended it to Shikasteh (broken) and Naskh scripts, enhancing precision and clarity in the teaching and practice of Persian calligraphy.

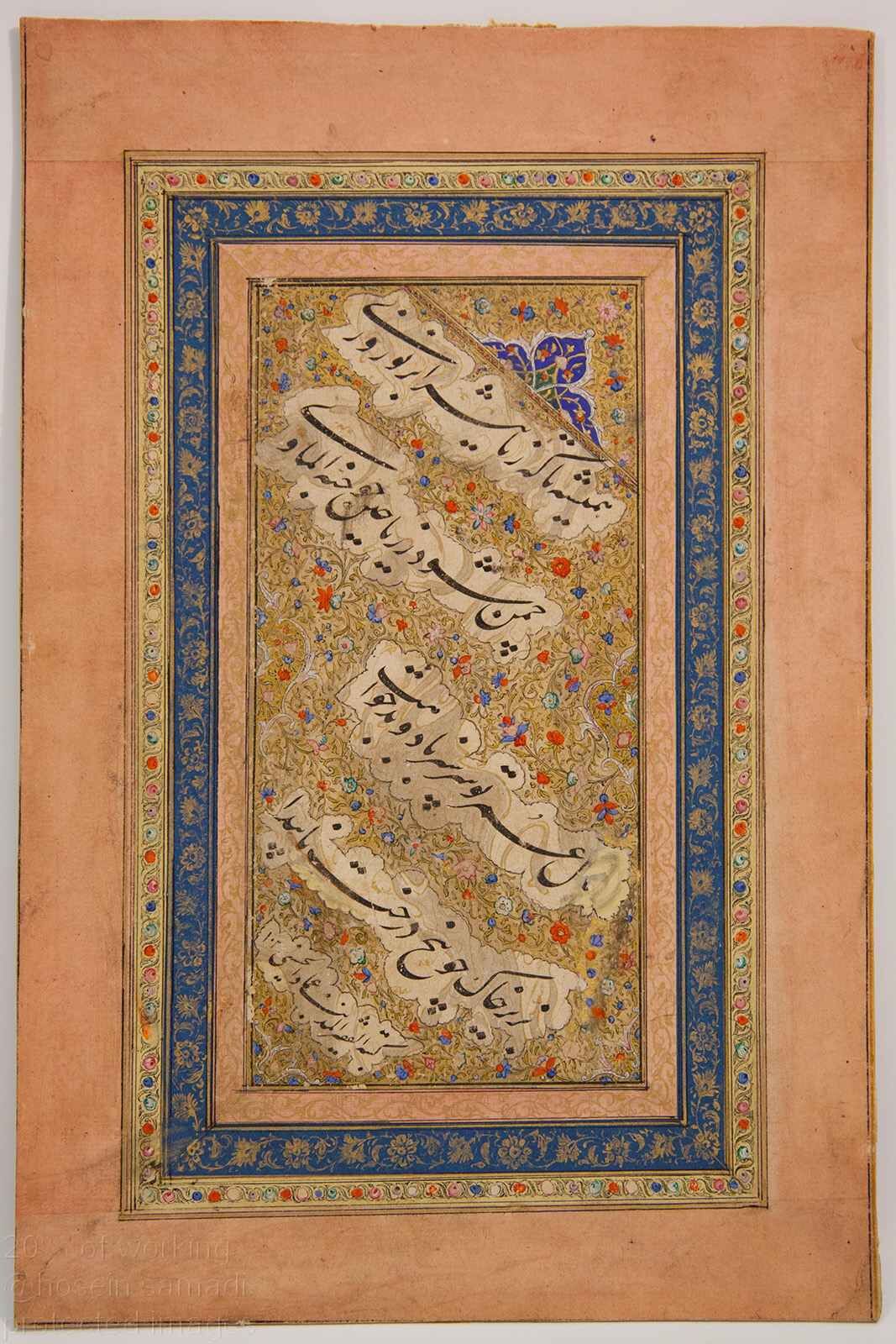

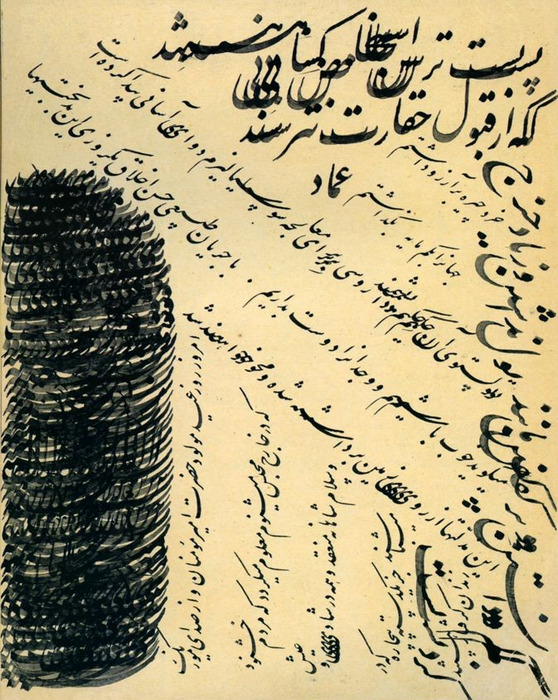

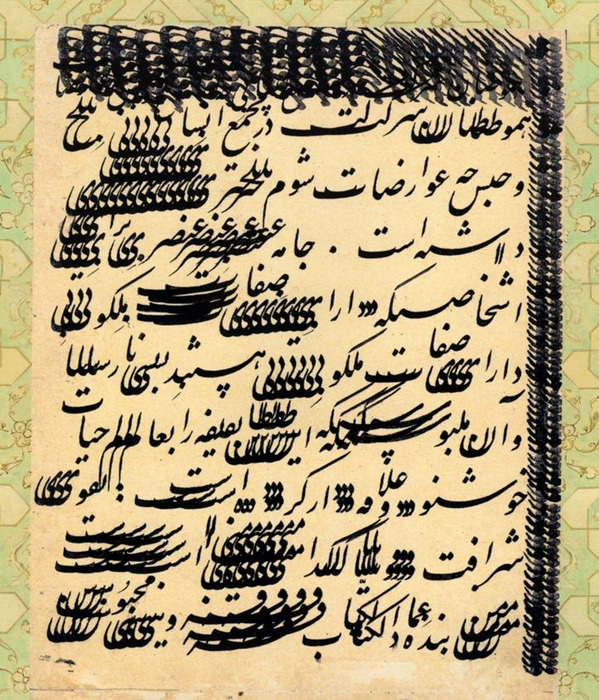

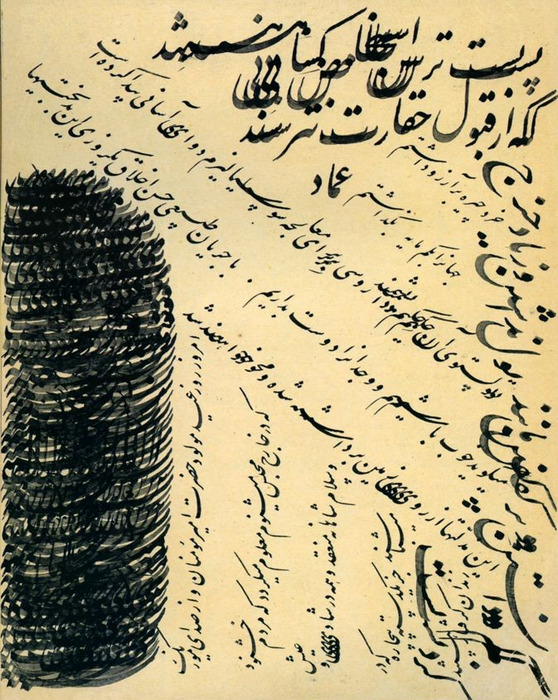

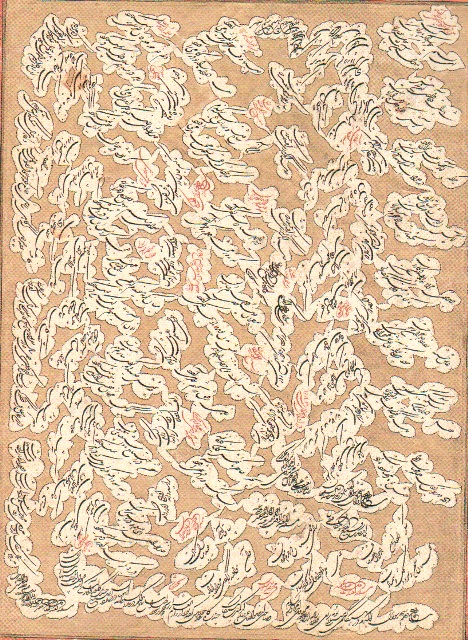

Lasting Contributions of Emad al-Ketab to Iranian Calligraphy

One of Emad al-Ketab’s greatest and most enduring contributions to Iranian calligraphy was the creation and publication of a 36-volume self-instruction course titled “Rasm al-Mashq.” He compiled this work at his own expense with the aim of making calligraphy accessible to novice students, marking a highly influential step in reviving the art of calligraphy and strengthening its educational foundations. This innovative initiative brought the art of calligraphy into schools for the first time, transforming calligraphy instruction from an elite privilege—previously reserved for princes and wealthy court officials—into a more widely accessible art form. Through this effort, Emad al-Ketab played a pivotal role in reviving the continuity of traditional calligraphic schools after a period of disruption. Additionally, his smart approach facilitated the dissemination and popularization of Mirza Reza Kalhor’s style, in which he himself was a key follower, ensuring that this prominent calligraphic method reached a broader audience and was preserved for future generations. In addition to calligraphy, Emad al-Ketab had a keen interest in painting, illumination (tazhib), poetry and literature, music, and photography, and he even experimented creatively in some of these arts, such as painting. In 1933 CE (1312 AH Solar), the National Works Association commissioned him to inscribe the epigraphs at the tomb of Ferdowsi, the renowned Iranian poet, in Tus. Following this, he adorned the Dar al-Fonun, Daneshsara-ye ‘Ali (Higher Teacher Training School), University of Tehran, and the Faculty of Theology and Islamic Studies (Daneshkade-ye Ma‘qul va Manqul, University of Tehran) with elegant inscriptions. In the same year, he was awarded the First-Class Culture Medal by the Ministry of Education. A large number of works by Emad al-Ketab have survived, primarily in the forms of siyah-mashq (densely written practice sheets), chhelipa (diagonal calligraphic panels), and line compositions, with siyah-mashq being the most predominant among them.

In the final analysis, Emad al-Ketab played two key roles in the history of Iranian calligraphy. The first role was his effort to preserve and transmit the tradition of Nastaliq script within the education system, ensuring that Persian calligraphy did not fade during the period of Western cultural influence, the Constitutional Revolution, and the early Pahlavi era. The second role, which is perhaps even more defining, stems not from his numerous and magnificent manuscripts, but from his diverse and expressive siyah-mashq works, which established him as a calligrapher with a distinctive personal style. These siyah-mashq pieces, which reached a peak of creativity during his imprisonment by the Punishment Committee, continued deliberately and consciously after his release. Building on the foundation laid by Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor in the siyah-mashq form, Emad al-Ketab introduced rhythmic and musical qualities to this calligraphic template, enhancing both its aesthetic and expressive dimensions

In his siyah-mashq works, Emad al-Ketab adopted a distinctive narrative approach, both visually and in terms of the textual meaning. This characteristic clearly distinguishes his style from the siyah-mashq works of the Qajar period. Moreover, Emad al-Ketab’s effective and remarkable efforts in reviving and advancing the art of calligraphy ensured the preservation and continuity of this authentic Iranian-Islamic art. Through his passion, dedication, steadfastness, and tireless endeavors, he safeguarded the Persian script from the storms of historical upheavals and forgetfulness, presenting it as a valuable heritage to future generations.

Emad al-Ketab passed away on 26 Tir 1315 SH (July 17, 1936) in Tehran at the age of 75. His body was laid to rest at Imamzadeh Abdullah in Shahr-e Rey.

Surviving Artistic Works of Emad al-Ketab

The surviving works of Emad al-Ketab can generally be categorized into three main groups:

a) Manuscripts: The Shahnameh of Ferdowsi, which marked the beginning of Emad’s fame and earned him the title Emad al-Ketab from Mozaffar al-Din Shah.

b) Inscriptions (Khat) on buildings: Various kufic and naskh inscriptions adorning mosques, schools, and public buildings.

c) Individual pieces and documents: Calligraphic panels,siah-mashq(practice sheets), letters, official decrees, and paintings, many created during his imprisonment for collaborating with the Committee of Punishment.

Notable surviving works include:

- Rasm al-Mashq (Calligraphy manual)

- Shahnameh of Ferdowsi (Amir Bahadri version)

- Tarji‘band by Hatef Isfahani

- Awsaf al-Ashraf

- Alf al-Nahar

- Stanley’s Africa travelogue

- Letters of Naseri scholars

- Accounting records of Musi Khan

- A copy of the Quran (Nafis Quran)

- Kitab-e Mohseniyeh

- The Constitution (Qanun Asasi)

- Bisotun inscription

- School of Rezaieh inscription

- Hadith-e Velayat inscription

These works collectively highlight Emad al-Ketab’s mastery across calligraphy, epigraphy, and documentation, reflecting his pivotal role in preserving and elevating Persian calligraphy.

| Name | Emad al-Ketab: Reviver of Persian Calligraphy |

| Country | Iran |

| Type | Calligraphy |

Gholamhossein Amirkhani: The Father of Contemporary Iranian Calligraphy

Gholamhossein Amirkhani: The Father of Contemporary Iranian Calligraphy

| Name | Gholamhossein Amirkhani: The Father of Contemporary Iranian Calligraphy |

| Country | Iran |

| Type | Calligraphy |

| awards | International |

Choose blindless

Red blindless Green blindless Blue blindless Red hard to see Green hard to see Blue hard to see Monochrome Special MonochromeFont size change:

Change word spacing:

Change line height:

Change mouse type:

(7)_1_1.jpg)