Yalda Night

Yalda: Written by Ali Bolukbashi

In the past, Iranians observed several different New Year’s Days, one of which was the first day of Dey. This day marked the end of one cosmic cycle and the beginning of another with the arrival of winter. Yalda night was regarded as the birthday of the Yazata Mehr or Mithra and the rebirth of the sun, the symbol of light and love. Al-Biruni referred to Yalda—the night marking the beginning of winter (the winter solstice)—as the “Greater Birth,” equating it with the twenty-fifth of Kanun al-Awwal (the third Syriac month), which in the Roman tradition corresponded to Christmas.

Yalda Night coincides with the beginning of the Great Winter Cheleh. According to ancient custom, people stay awake past midnight—and sometimes until dawn—gathered around the mizd or shab-chareh spread. Iranians in different regions decorate this table with a variety of summer and autumn fruits and snacks—especially pomegranates and watermelons. Through eating fruits and nuts, storytelling, and divination with Hafez’s poetry, they try to ward off the ill omen of this longest night by staying awake and symbolically “breaking the back of the demon of darkness” with the rising of the winter sun.

| Name | Yalda Night |

| Country | Iran |

| State | East Azerbaijan |

| City | Azarshahr |

Yalda Night

Yalda Night (Shab-e Chilleh) – The Ancient Iranian Celebration of the Longest Night

Yalda Night, also known as Shab-e Chilleh, is one of the oldest Iranian celebrations. This festival commemorates the passing of the longest night of the year and the subsequent lengthening of days in the Northern Hemisphere, coinciding with the winter solstice. Another name for this night is Chilleh, as the celebration itself is an ancient Iranian ritual.

Timing and Traditions

Yalda refer to the time span from sunset on the 30th of Azar (the last day of autumn) to sunrise on the 1st of Dey (the first day of winter). On Yalda Night, Iranian families usually prepare an elaborate dinner along with a variety of fruits—most commonly watermelon and pomegranate—and enjoy them together. Afterward, traditions such as reciting the Shahnameh, storytelling by elders, and divination using Hafez’s poetry (Fal-e Hafez) are widely practiced.

Origin of the Name and Other Terms

The word “Yalda” is derived from the Syriac word ܝܠܕܐ, meaning “birth.” The term Shab-e Chilleh (Chilleh Night), synonymous with Yalda Night, comes from the tradition of dividing winter into two periods: the first forty days, called Chilleh Bozorg (the Great Chilleh), and the following twenty days, called Chilleh Koochak (the Small Chilleh).

The scholar Abu Rayhan Biruni referred to this celebration as “Milad Akbar” (the Great Birth), interpreting it as the birth of the sun. In his work Al-Athar al-Baqiyah, the first day of Dey (the first month of the Iranian calendar) is mentioned as “Khur” (Sun). In the Masudi Law manuscript preserved at the British Museum in London, this day is recorded as “Khoreh Rooz”, though some sources call it “Khorram Rooz.”

Chilleh refers to two calendrical periods in a solar year that have cultural significance: one at the beginning of summer (Tir) and the other at the beginning of winter (Dey). Each period consists of a “Great” part (forty days) and a “Small” part (twenty days). The word Chilleh is derived from “chehel” (forty) and simply indicates the passing of a certain period, not necessarily forty days.

Background

Yalda Night, considered one of the sacred nights in ancient Iran, was officially included in the Iranian calendar in 502 BCE during the reign of Darius I. Chilleh (the seasonal period) and the celebrations held on this night are part of an ancient tradition. In the distant past, people who lived closely with nature, agriculture, and the changing seasons organized their activities according to the sun’s movement, seasonal changes, the length of day and night, and the positions of stars.

They observed that during certain days and seasons, the days became longer, allowing greater use of sunlight. This led to the belief that light and the sun symbolize goodness and favor, while darkness represents struggle and conflict. Ancient peoples, including Indo-Iranian and Indo-European tribes, realized that the shortest day occurs at the end of autumn and the first night of winter, after which days gradually lengthen. They called this the “birth of the sun” (Mithra) and marked it as the beginning of the year. The Christian Christmas also has its roots in this belief.

In ancient Zoroastrian culture, the year began with the cold season. In the Avesta, the word “Sareda” or “Saredh” conveys the concept of “year” and literally means “cold,” symbolizing the triumph of Ohrmazd (Ahura Mazda) over Ahriman—light over darkness.

Yalda is the first night of winter and the last night of autumn, corresponding to the beginning of Capricorn (Jadi) and the end of Sagittarius (Qaws). It is the longest night of the year, and the sun enters the sign of Capricorn on or around this night. This night was considered inauspicious by ancient Iranians because darkness, representing Ahriman, was at its peak. To combat this, people lit fires and gathered to eat, drink, celebrate, dance, and converse, spreading a ceremonial table with fresh and dried fruits, as well as nuts.

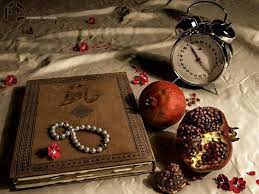

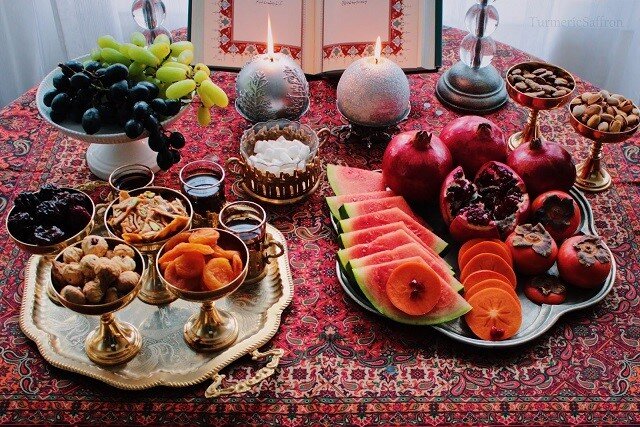

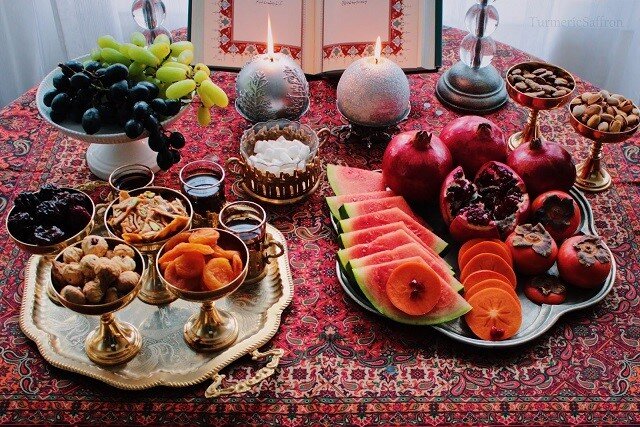

The Yalda table, called “Myazd”, included seasonal fruits and nuts (called Lork by Zoroastrians), prepared in honor of Ahura Mazda and Mithra. In ancient rituals, every festival featured a table with sacred foods, seasonal produce, and ritual items such as fire altars and ceremonial vessels.

Yalda Night is considered the night of the birth of the Sun God, justice, covenant, and war. There are two main narratives associated with it:

Mithra (Mehr) returns to the world, lengthening daylight hours and demonstrating the triumph of the sun. The Mithraic religion predates Zoroastrianism and was widely practiced in the eastern Mediterranean.

Some researchers note that a prophet was born on Yalda Night in 196 AD (51st year of the Parthian Empire), rescued from water by two dolphins, reflecting the Mithraic significance of water.

Connections with Other Cultures

Winter solstice celebrations were common among other ancient peoples. In Rome, the worship of Sol Invictus (Unconquered Sun) was celebrated at the winter solstice, coinciding with Roman Mithraism. Scholars have observed that elements of Christmas—including lighting candles, decorating trees, staying awake, feasting, and visiting friends—mirror ancient Yalda traditions.

The Yalda Table

To celebrate Mithra’s birth, families prepare a Yalda or Chilleh table decorated with dried fruits, pomegranate seeds, watermelon, and assorted nuts. Red fruits, such as pomegranate, watermelon, red apples, and senjed (oleaster fruit), symbolize sunlight, reflecting ancient Mithraic beliefs.

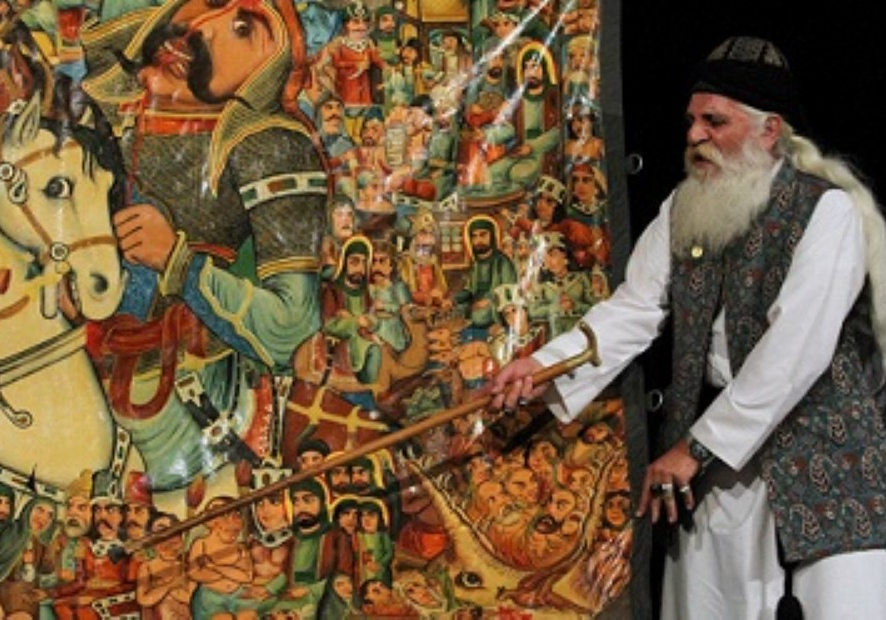

Shahnameh Reading and Hafez Divination

Reading the Shahnameh is an inseparable part of Yalda Night. Families also consult Hafez’s Divan for divination, while those skilled in poetry recite their own verses. These customs preserve remnants of ancient Mithraic culture and are renewed every year.

Yalda in Persian Poetry

The pomegranate, a fruit native to Iran, features prominently in Persian literature:

Saadi: “The day of your blossoming… as if Yalda Night rose from the Day of Judgment.”

Hafez: “The company of tyrants is the darkness of Yalda Night; seek the light of the sun that will emerge.”

Sohrab Sepehri, Khayyam, Ohadi Maraghei, Khaju Kermani, and others also reference Yalda Night in poems highlighting love, longing, and the symbolic battle of light over darkness.

Yalda Across Greater Iran

From Greater Khorasan to Kashmir, the “Chilleh-ye Bozorg” (Great Chilla) is observed. In Afghanistan, northern India, Pakistan, and among the Tajiks, it is known as Chilleh Kalan. In Mazar-i-Sharif, Balkh Province, the culturally rich population observes similar rituals during the Great Chilla.

Regional Yalda Traditions in Iran

Khorasan: Special rituals such as Kafbikh or Bikh Zani are performed. Kaf-bikh is a sweet foam prepared using the root of a plant called bikh, boiled and beaten until stiff, sweetened, and garnished with walnuts and pistachios. Wedding ceremonies, Sar-Hammami, and Henna Night (Hanna-Bandan) often coincide with Yalda. Gifts, called Khomcheh, are exchanged between the bride and groom’s families.

Isfahan (Dehaghan County): Families gather around the korsi, enjoy fruits and nuts, read Shahnameh, perform Hafez divination, and newlyweds exchange gifts or a khoncheh. Typical foods include polo mahi, koofteh, dolmeh, and sweets.

Azerbaijan (East and West): Decorated trays (khoncheh) are sent to newlyweds’ families. Watermelons are adorned with red scarves; in the north, a large decorated fish is presented.

Kurdistan: Called Shu Chille, families prepare dolma and sangak bread for guests in Sanandaj.

Bushehr: Families celebrate at elders’ homes, with watermelon as a central feature.

Dasht-e Gorgan (Golestan Province): Families gather around the korsi, read Hafez and Shahnameh, and enjoy fruits, garden and forest produce, and local sweets like mat and kasmak.

Fars (Shiraz): The Yalda table is as colorful as Nowruz, with citrus fruits and watermelon for cold-tempered individuals, and dates and ranginak for warm-tempered ones. Hafez reading is essential.

Hamedan: Practicing Fal-e Sozan (Needle Fortune), people sit around an elder reciting poems, interpreting fortunes, and consuming seasonal snacks.

Ardabil: Families gather, sharing watermelon, pomegranate, oranges, seeds, and rice with fish. Decorated watermelon is sent to newlywed brides.

Gilan: Watermelon is considered essential. Avokonus (medlar preserved in water and salt) is a traditional treat. Special platters with fruits, nuts, sweets, and a fresh fish for newlyweds bring blessings.

Khuzestan: Families stay awake to welcome Qarun, who brings symbolic wood turning into gold. Foods include nuts, watermelon, pomegranate, sweets, dates, cooked beets, ash, and more.

Qazvin: Elders lead gatherings with Shab-Chareh (red fruits), sabzi-polo with smoked fish, and treats like raisins, walnuts, and dried figs. Grandmothers predict weather events, and Khoncheh-ye Chelleh is sent from the groom to the bride.

Lorestan and Lorestān: Known as Shu Cheleh or Shu Aval Qareh, activities include family gatherings, Chahār-Sarv fortune-telling, Hafez divination, preparing wheat, sesame, and nut snacks, and stretching shawls from rooftops to collect treats. Teens recite poems:

“Emshab Aval Qareh, khair de hunet bware” — Tonight is the first night of winter; may goodness fall on your house.

“Nun o panir o shireh — keykha hunet namireh” — Bread, cheese, and syrup; may the head of the household not die.

“Chi be Ali Koochak biare” — Give something so that little Ali or your child may receive it. Children receive nuts, sweets, fruits, and wheat with hemp seeds, repeat the verses in gratitude, and then continue to other rooftops.

| Name | Yalda Night |

| Country | Iran |

_1.jpg)

_1.jpg)

Choose blindless

Red blindless Green blindless Blue blindless Red hard to see Green hard to see Blue hard to see Monochrome Special MonochromeFont size change:

Change word spacing:

Change line height:

Change mouse type: