Reza Abbasi: The Pinnacle of the Isfahan School of Persian Miniature Painting

Reza Abbasi: The Pinnacle of the Isfahan School of Persian Miniature Painting

Reza Abbasi, son of Ali Asghar Kashani (a renowned painter in Shah Tahmasp’s court), is considered one of the most distinguished figures in the history of Iranian visual arts, whose name is inseparably linked with the Isfahan School of painting. He was born around 970 AH into an artistic family and learned portraiture and illustration from his father, following the traditional path of his time. Although Reza Abbasi was born in Mashhad—his father named him Reza in honor of Imam Reza (AS)—he spent some time in Qazvin. It was during this period that his artistic maturity and talent became evident in the courts of Shah Ismail II and Sultan Muhammad Khodabandeh. Sadeqi Beyk Afshar, who was then an elder and head of the royal workshop, was so astonished by Reza Abbasi’s delicate and refined technique that, in his later years, he attempted to adapt his own style to emulate that of Reza Abbasi. In 995 AH, Reza Abbasi joined the court of Shah Abbas I, where he spent much of his artistic life in Isfahan. His unique artistic perspective and technique influenced all forms of visual arts of that era—including mural painting, manuscript illumination, tile design, carpet and textile design, handicrafts, gilding, and decorative ornamentation—and its influence reached its zenith during the first half of the 11th century AH. His methods continued to serve as a model for later generations of artists, and contemporary Iranian painters—especially those of Isfahani heritage, such as Mahmoud Farshchian, Javad Rostam Shirazi, Jazi-Zadeh, and Yesayi Shajaniyan—remain deeply influenced by his style and approach.

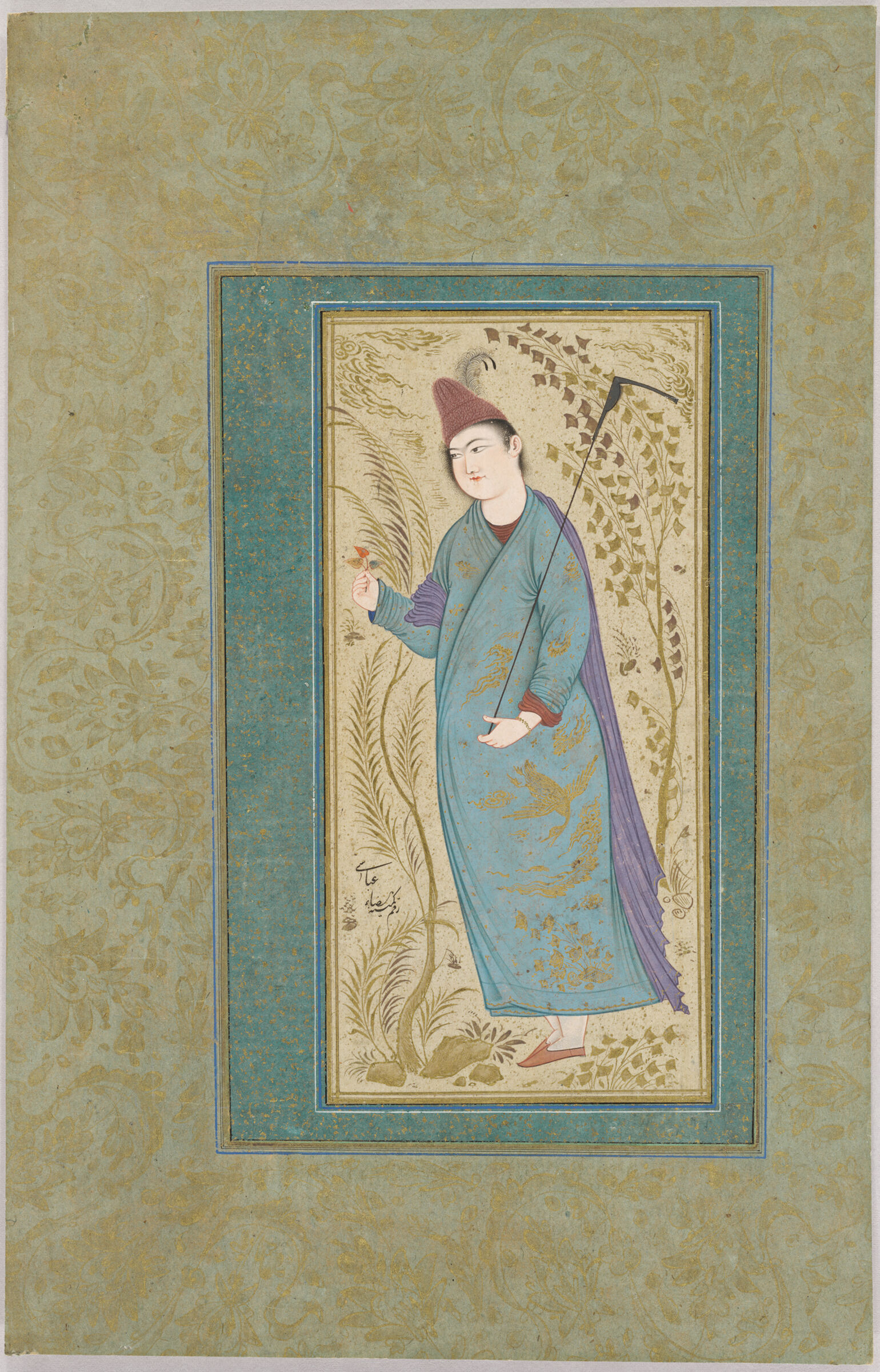

Seated Youth, by Reza Abbasi

Chronology of Reza Abbasi’s Artistic Life

Based on primary historical documents and the surviving works of Reza Abbasi from the late 10th century AH to the mid-11th century AH, his artistic life can be divided into four major periods:

A) From birth to adolescence – During this time, he worked alongside his father with the painters and artists in the workshop of Ebrahim Mirza in Mashhad and was later transferred to the royal workshop of Shah Ismail II in Qazvin. This period continues until 996 AH, when he joins the circle of artists serving Shah Abbas I. (983–996 AH)

B) Around the second decade of the 11th century AH – For various reasons, he gradually withdraws from active participation in the royal workshop. (1011–1022 AH)

C) From approximately 1022 AH until his death – In this period, the depiction of figures, themes, and his artistic style undergoes notable changes. (1022–1044 AH)

First Period

The first identifiable period in Reza Abbasi’s works corresponds to the years when he moved from Mashhad to Qazvin and began working in Shah Ismail’s workshop. Having spent his adolescence in Ebrahim Mirza’s workshop in Mashhad, he became familiar with the early secrets and techniques of painting.

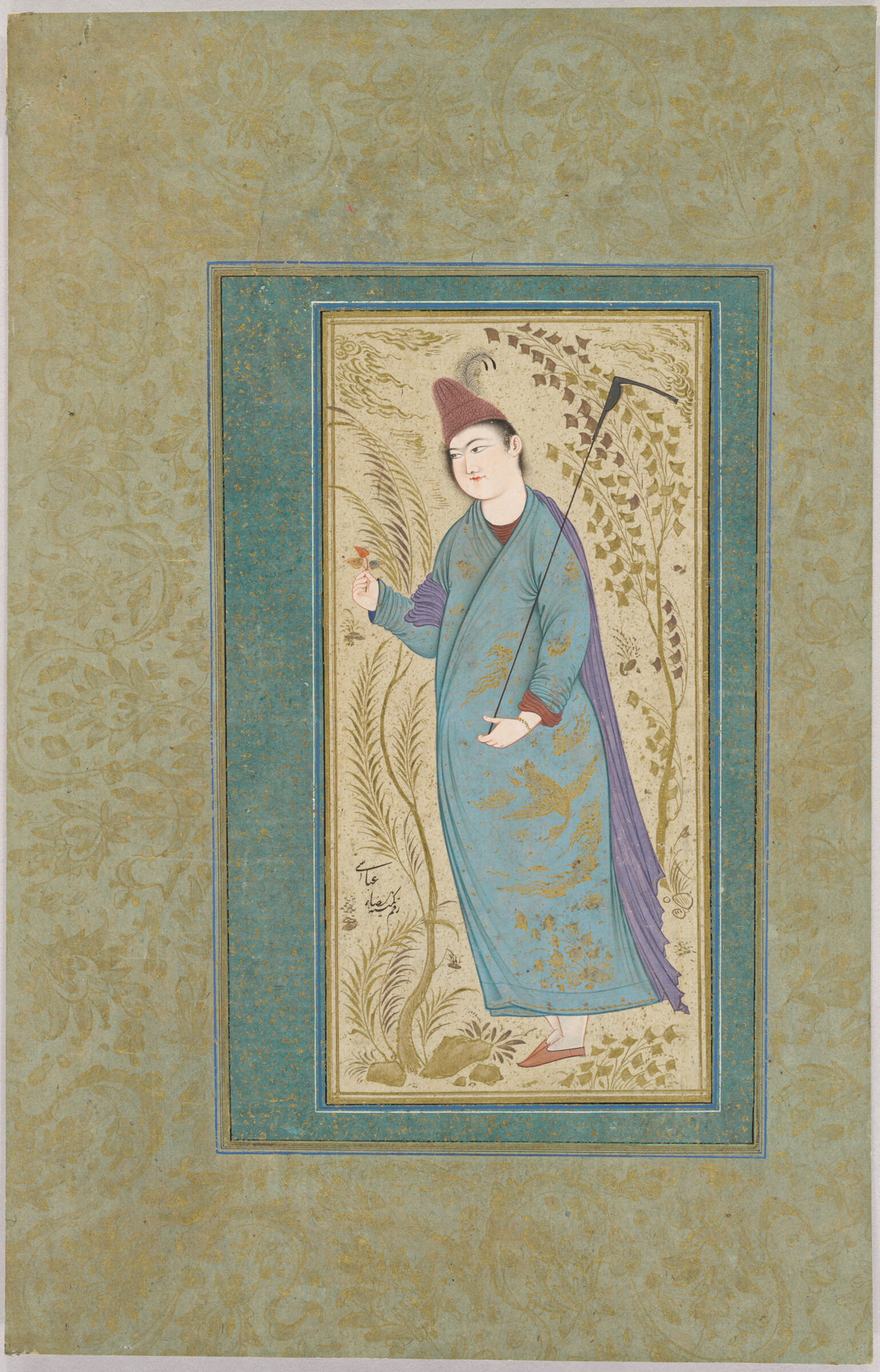

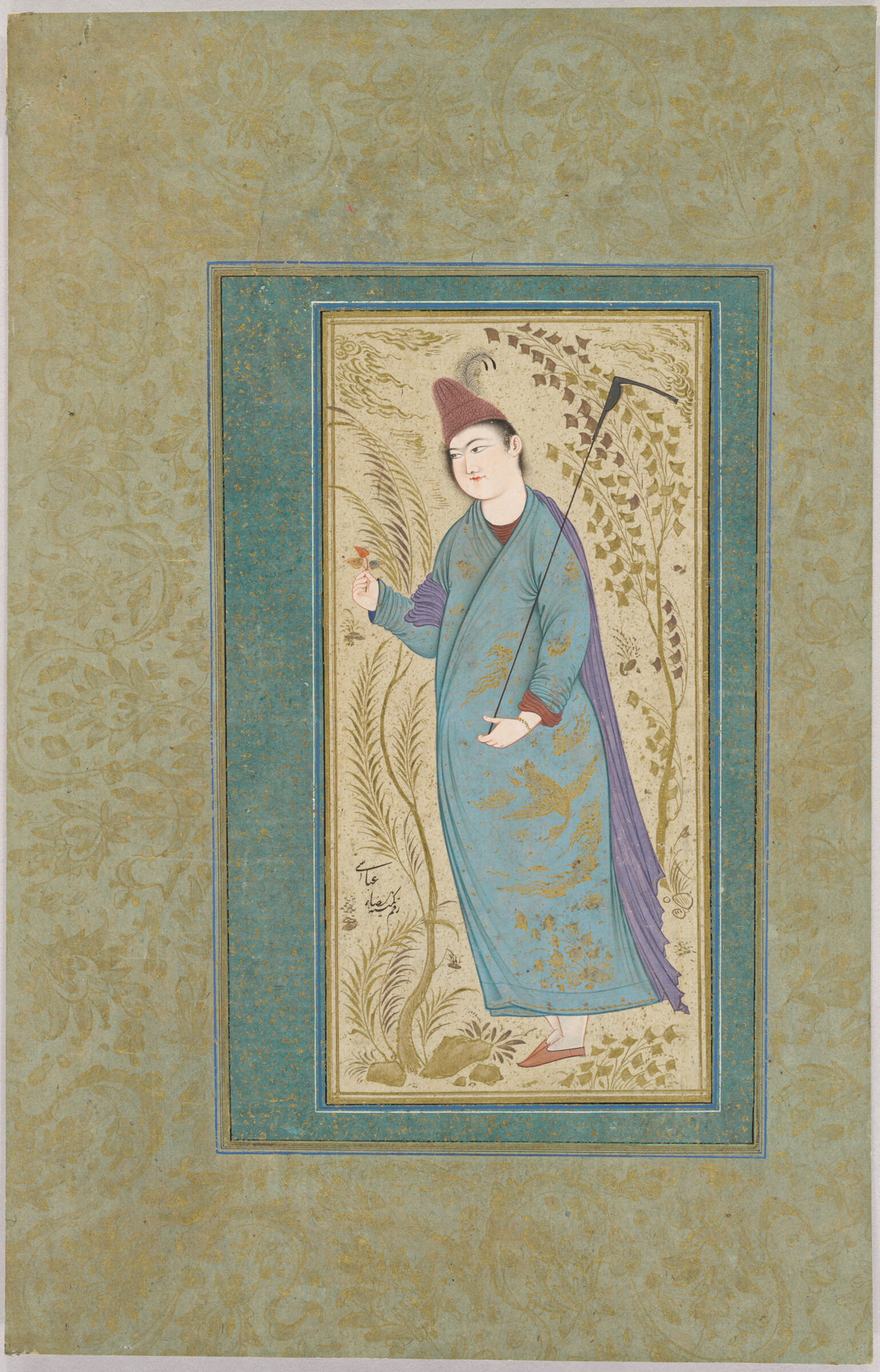

Works from this period are characterized by delicate coloring, fine design, and meticulous brushwork. Most single-leaf paintings from this time feature colored figures against cream-colored backgrounds. Prominent elements include large, voluminous turbans often adorned with flowers or birds, and young figures holding floral branches. These works are generally known as single-leaf (takbarg) or single-figure (tak-peykar)

Young Man in Dervish Attire, by Reza Abbasi

Middle Period

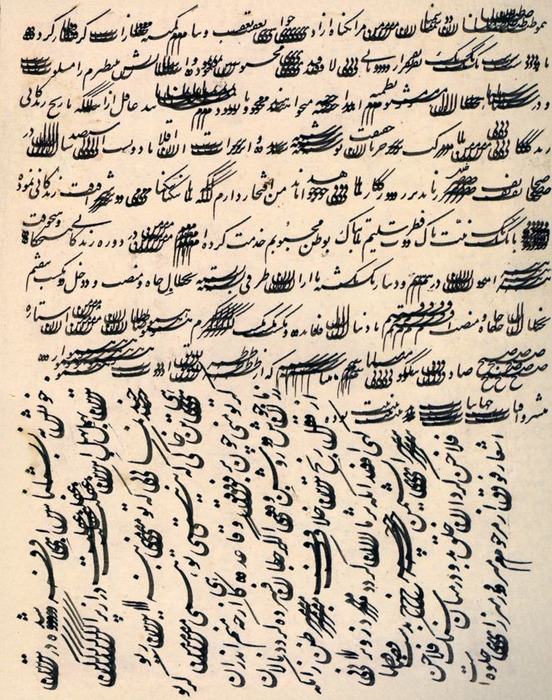

The second or middle period of Reza Abbasi’s artistic life corresponds to the time when he withdrew from the royal workshop or engaged less in work associated with the courtly atelier. The subjects of his works in this period are primarily social and everyday life scenes, depicting groups such as dervishes, shepherds, hunters, street vendors, tricksters, and cockfighters. Most of these works were created in monochrome or as finely detailed line drawings. Thanks to his exceptional skill, Reza Abbasi was able to execute these pieces directly with brushwork, without preliminary sketches, demonstrating a spontaneous and fluid mastery of the medium. Using smooth, flowing lines, he captured the movements and expressions of his figures with remarkable speed and coordination. Many of these works were produced on scraps of paper, indicating limited financial resources compared to the period when he worked in the royal atelier. Despite such constraints, the richness of his line, technical precision, and extraordinary skill elevate these works, giving them a distinct and admirable quality. In this period, line dominates over color, highlighting Reza’s mastery and the expressive power of drawing itself. Notably, this era marks the first time he emphasized drawing as an independent artistic branch, capable of standing alone as a medium of expression. While painting had gradually become less connected to textual illustrations in preceding decades, Reza Abbasi’s approach gave independent drawing and painting their full significance, freeing them from their reliance on books. Most works from this period are unsigned, and stylistically, the brushwork and compositional elements show continuity with some aspects of his early period. These pieces often reflect Reza’s visits to ordinary people, wrestlers, and dervishes, capturing the vitality of everyday life outside the royal court.

Final Period

After about a decade, Reza Abbasi returned to the royal workshop and regained the favor and patronage of Shah Abbas. Part of his artistic activity during this period involved illustrating manuscripts, such as the Golestan of Saadi (1024 AH, written in Mir Emad’s hand), which includes six miniatures. Reza Abbasi apparently oversaw the illustration department for this manuscript. One of the six miniatures, titled “The Dispute of Saadi and the Claimant,” was executed by Reza Abbasi himself, while the remaining miniatures were either carried out by his students, including Afzal al-Hosseini, under his supervision or at least designed and composed by Reza, with other stages such as coloring and construction completed by his pupils. Another example of his mastery from this period is the Khosrow and Shirin manuscript by Nezami, containing eighteen miniatures signed by Reza Abbasi or produced in collaboration with his students toward the end of his life (1042 AH). Additionally, the Makhzan al-Asrar manuscript by Haidar Khwarazmi, in which Mir Emad is credited as the calligrapher, includes nine miniatures attributed to Reza Abbasi, completed in 1023 AH, showcasing his continued skill in manuscript illustration and artistic supervision during the final stage of his career.

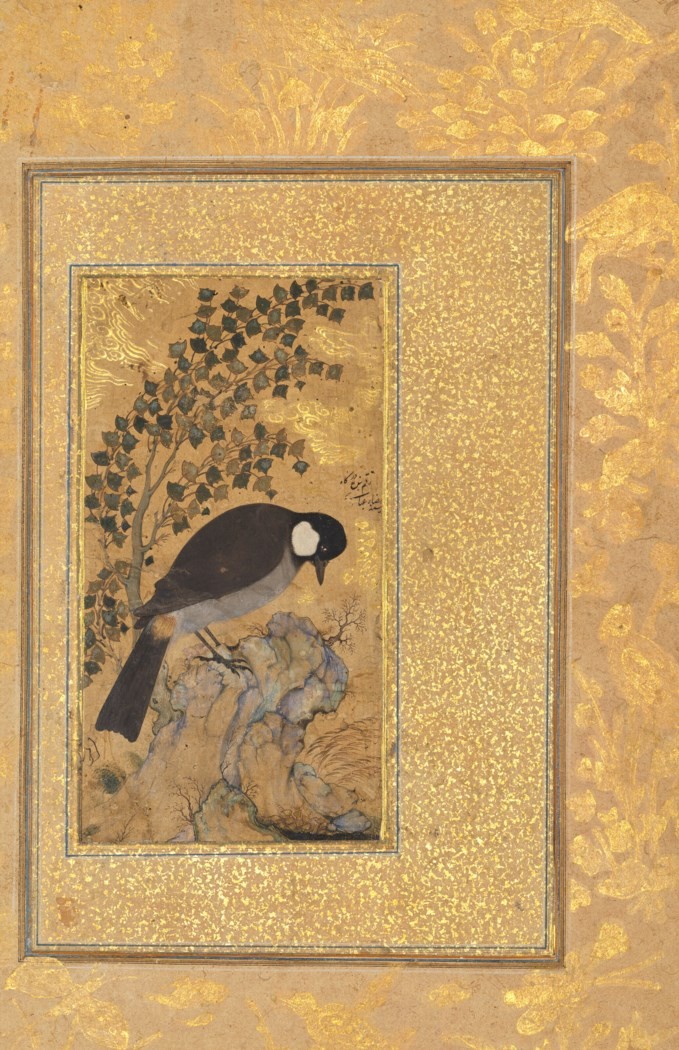

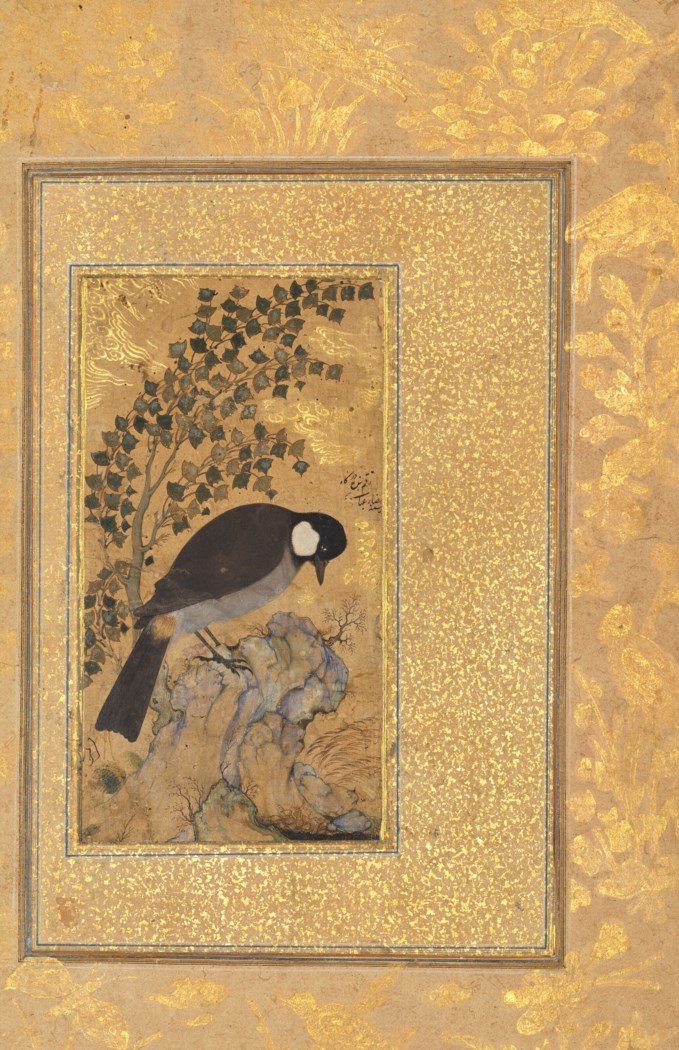

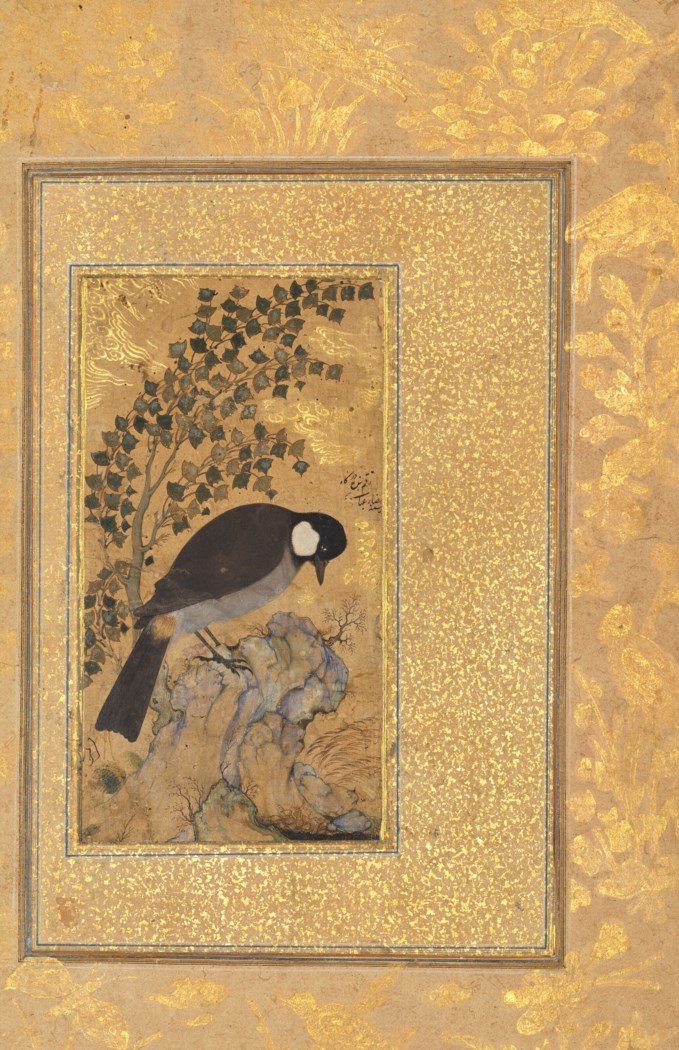

“White-Eared Nightingale” by Reza Abbasi

In the early period of his artistic career, when Reza Abbasi joined Shah Abbas’s court in Qazvin and worked under the supervision of Sadeghi Beyk Afshar, he also contributed to preparing a manuscript of the Shahnameh of Shah Abbas. This Shahnameh was compiled between 995 –1005 AH and contains fourteen illustrations. Four of these illustrations—such as The Killing of Rostam the White Elephant, Fereydun Rejecting the Ambassadors of Salm and Tur, Tahmoures Battling the Demons, and Fereydun Crossing the Sea—are attributed to Reza Abbasi.

Some of Reza Abbasi’s works from this period belong to the time after Shah Abbas I’s death; these include individual portraits of dervishes, particularly his spiritual teacher, Ghyath al-Din Semnani. Interestingly, the face of this elder mystic appears in many of the aged figures in Abbasi’s later works.

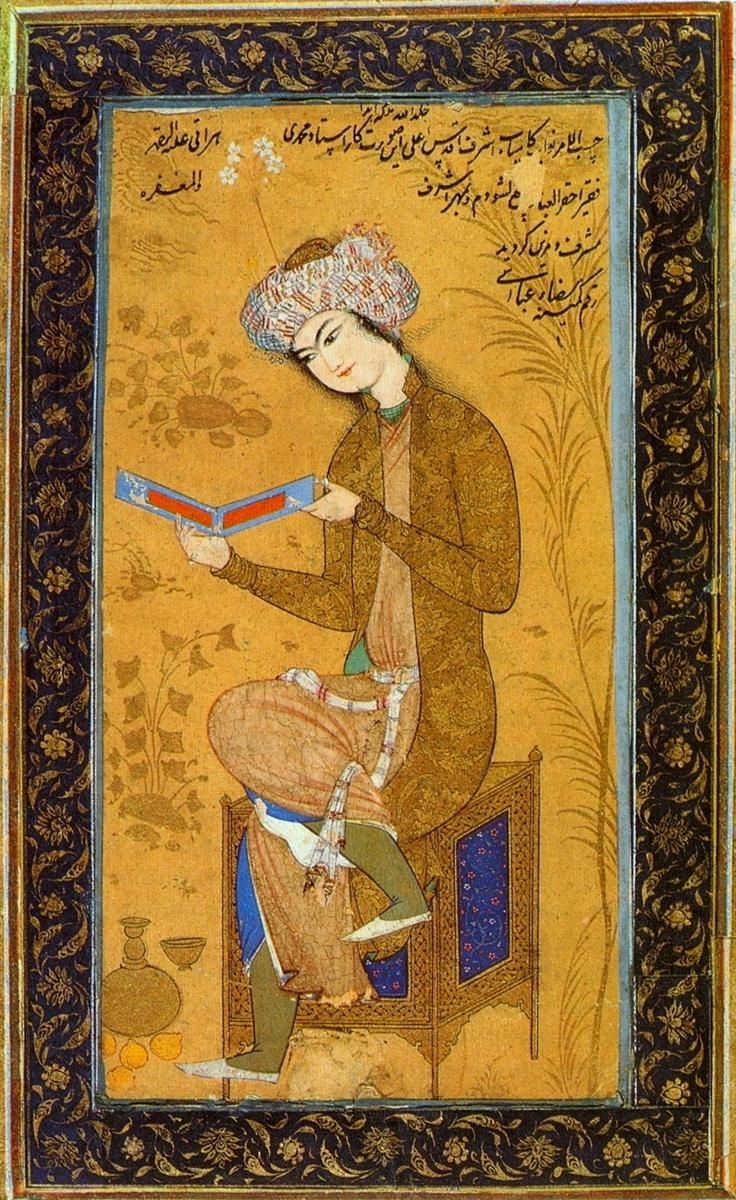

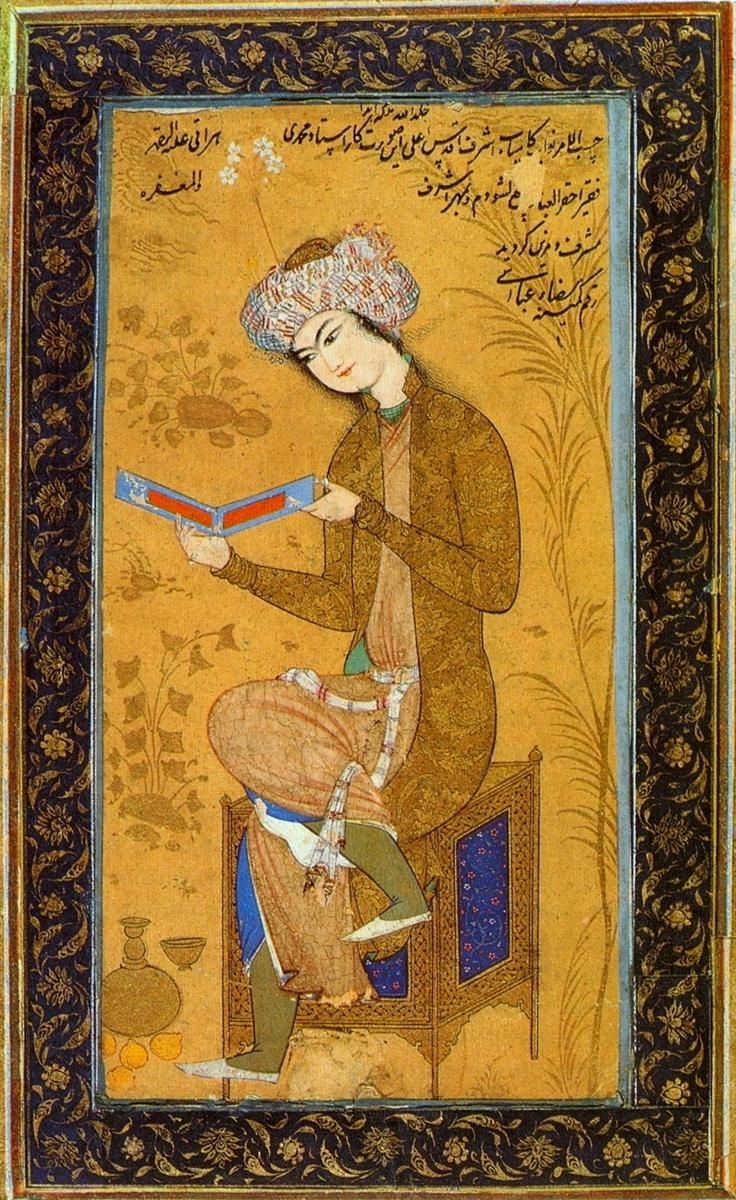

Another characteristic of Abbasi’s works in this period is that he reduces the number of figures in his compositions, enlarges the size of the figures within the frame, and confines them within the image boundaries. The youthful figures, often holding a flower branch or a cup of drink and gazing beyond the frame, convey a sense of dreaming and anticipation. This feature is consistently noticeable and significant in the youthful figures of Abbasi’s early period works as well.

Contemporary themes, such as the quality of the relationship between lover and beloved, plump and inactive body types, more luxurious coloring compared to earlier periods, along with precise and orderly lines and detailing, are among the other defining features of Reza Abbasi’s works in his final period.

Withdrawal from the royal atelier

Reza Abbasi collaborated with the royal atelier in Qazvin and Isfahan for nearly two decades and, in the first decade of the 11th century AH, was honored with the title “Abbasi” by Shah Abbas I. As Anthony Welch also noted, during the early decades of his career, Reza was reluctant to use the title Abbasi for himself and seldom included it in the signatures of his works from that period, as he considered the title a heavy burden on his independence. According to the writings of Qazi Mir Ahmad Monshi and Eskander Beyk Monshi, historians of Shah Abbas’s era, the reason for Reza’s withdrawal from the royal atelier should be sought partly in his interest in mingling with wrestlers and socializing with them, and partly in his personal disquiet. Sheila Canby, citing these two historians, believes that after the capital was moved to Isfahan and following the striking portraits Reza created of young Isfahanis, he abandoned court life, mingled with wrestlers, and became fascinated by their teachings. Between 1011-1019 AH, Reza stopped producing portraits of young men and wealthy individuals. Instead, he prepared and created designs depicting unusual, eccentric spaces and elderly figures set against dark and somber landscapes. Thus, much of Reza Abbasi’s socially themed designs and paintings, executed in a brush-and-ink style, were produced during the periods when he often visited the underprivileged, wrestlers, and places frequented by these social groups.

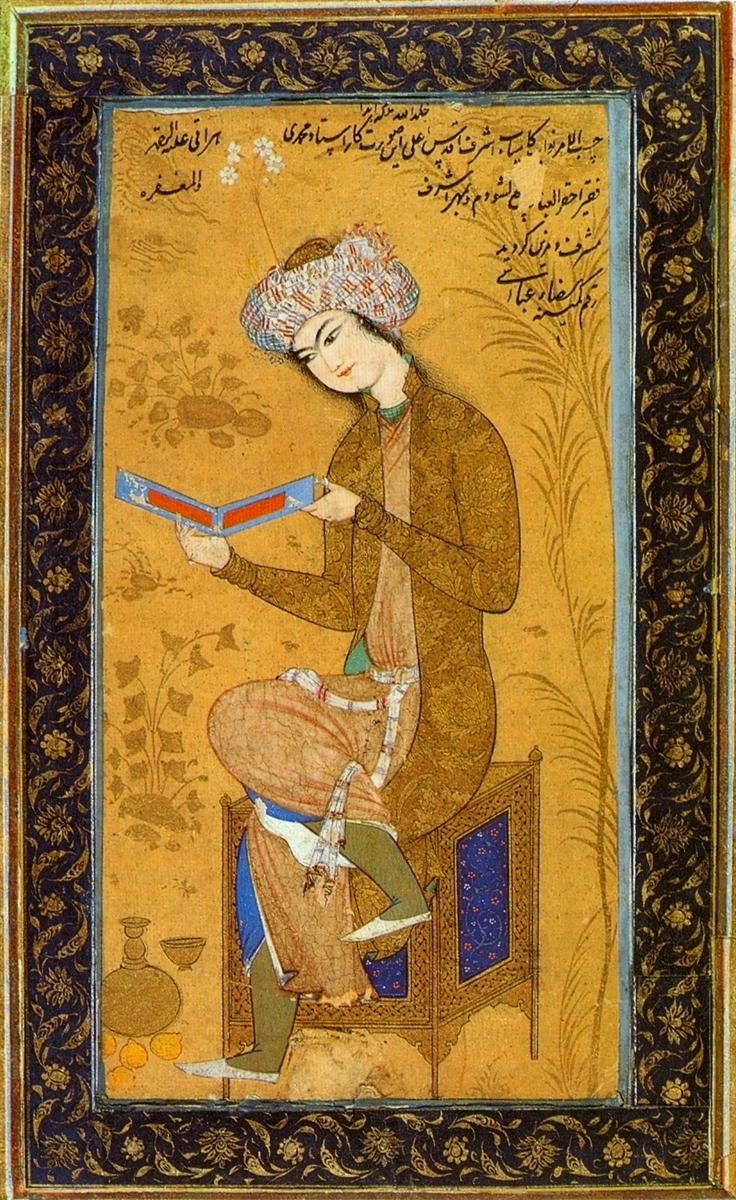

"A Young Man Reading," by Reza Abbas

"Return to the Royal Workshop"

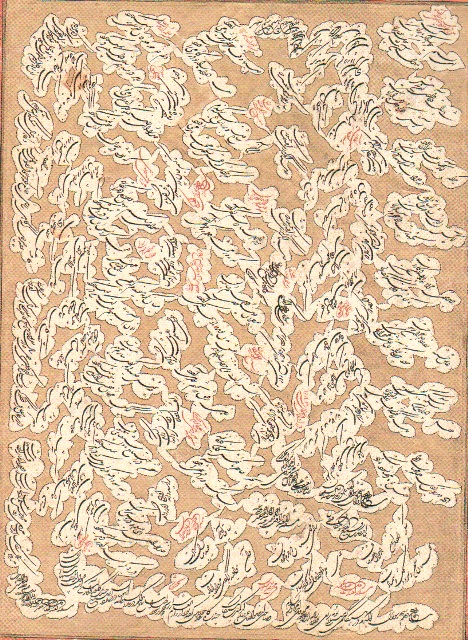

In the years after reaching fifty, Reza Abbasi’s thinking matured with his experiences in middle age. As relative calm prevailed in the country’s political, social, and intellectual environment, he became inclined—through the mediation of certain political figures—to return to the royal workshop. Until this period, he had rarely worked on illustrated manuscripts, but from this point onward, either personally or under his supervision, a number of manuscripts were illustrated. During this phase, Reza Abbasi began to express his personality and demeanor in a somewhat symbolic and mysterious manner. In many gatherings or single-page works, he depicted or painted a dervish’s face appearing in various roles. Strong evidence suggests that the recurring similarities among these faces indicate they represent a single individual—most likely Ghiyath al-Din Semnani, Reza Abbasi’s mentor and guide in Sufism. These single-page portraits—or “unique faces,” as referred to by Iskander Beyk Monshi—can be considered a form of idealized portraiture or figure representation, which Reza Abbasi established as a new artistic domain in Iranian painting, both in terms of quantity and conceptual significance. Reza’s single-page figures, while grounded on the earth, convey a sense of movement and lightness. The figures appear suspended within the image space, as if walking without fully placing their feet on the ground. This reflects the concept of “sūr-i mu‘allaq” (suspended forms) in the spiritual metaphysical realm, as discussed by sages and mystics. Even when depicting rulers or princes, his works convey a unique humility and simplicity alongside majesty and grandeur, demonstrating his distinctive approach to both form and meaning in painting.

Artistic Style and Approach of Reza Abbasi

The available documentation for identifying the style and approach of Reza Abbasi’s painting includes works he produced from the late 10th century AH onward, some of which bear his signature. In this period, his signature was “Mashqeh Agha Reza”. This period coincides with the transfer of the Safavid capital from Qazvin to Isfahan, which began in 996 AH and lasted for approximately ten years, until 1006 AH. Although the fully developed Isfahan school of painting emerged around 1009 AH with the maturation of Reza Abbasi’s style, the artistic outlook that shaped this school had already begun at least a decade earlier in Mashhad and Qazvin. For example, single-figure portraiture (tak-chehreh) was already common, but the diversity of characters and subjects—including soldiers, travelers, leisure scenes, villagers, dervishes, youth, as well as courtiers and attendants—began to flourish during Reza Abbasi’s middle-aged period, particularly while he was temporarily distanced from the royal workshop. This phase marks the transition from conventional courtly themes to a more varied, observational, and socially reflective approach, laying the foundation for his distinctive style and the eventual crystallization of the Isfahan school.

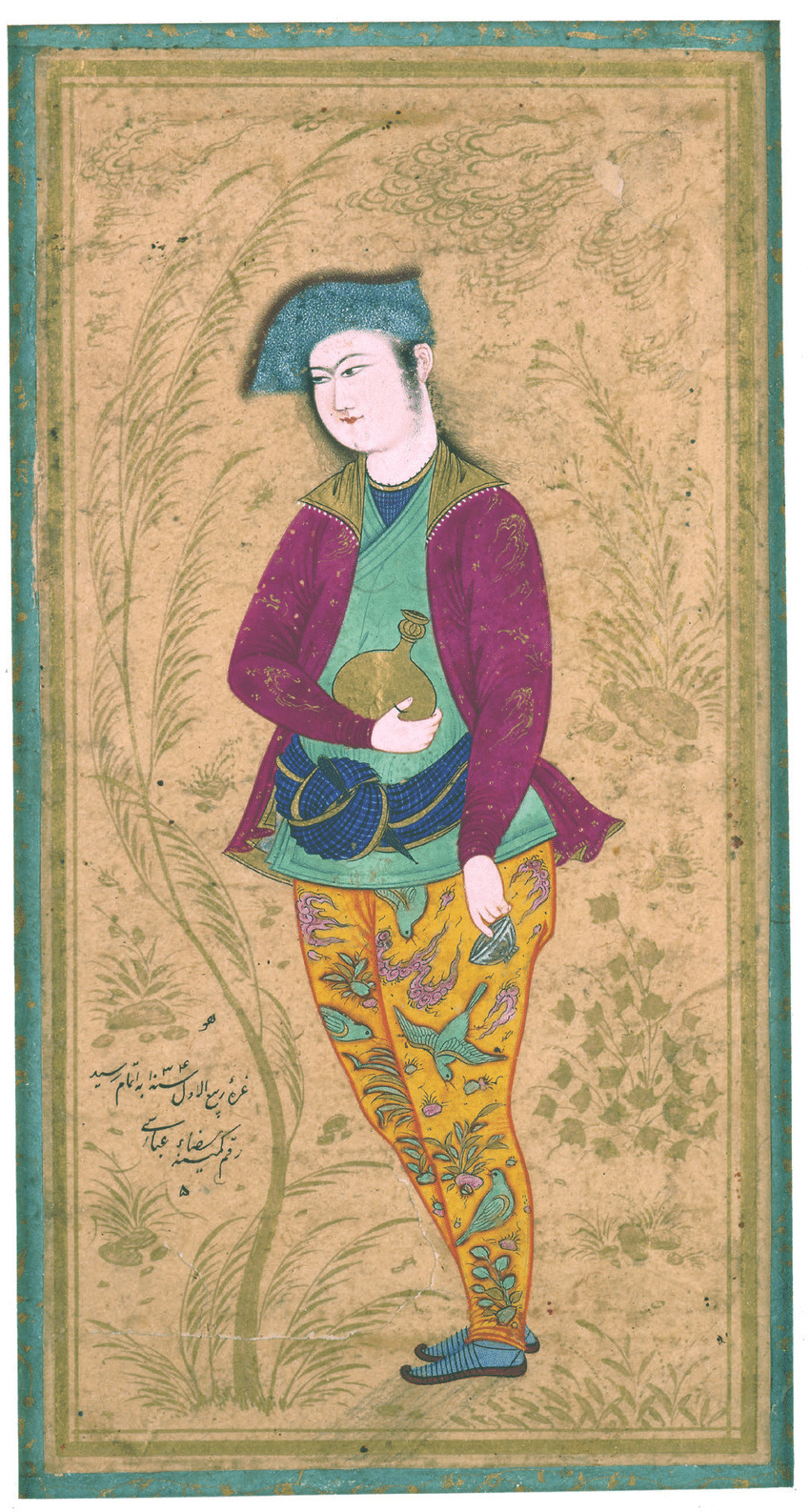

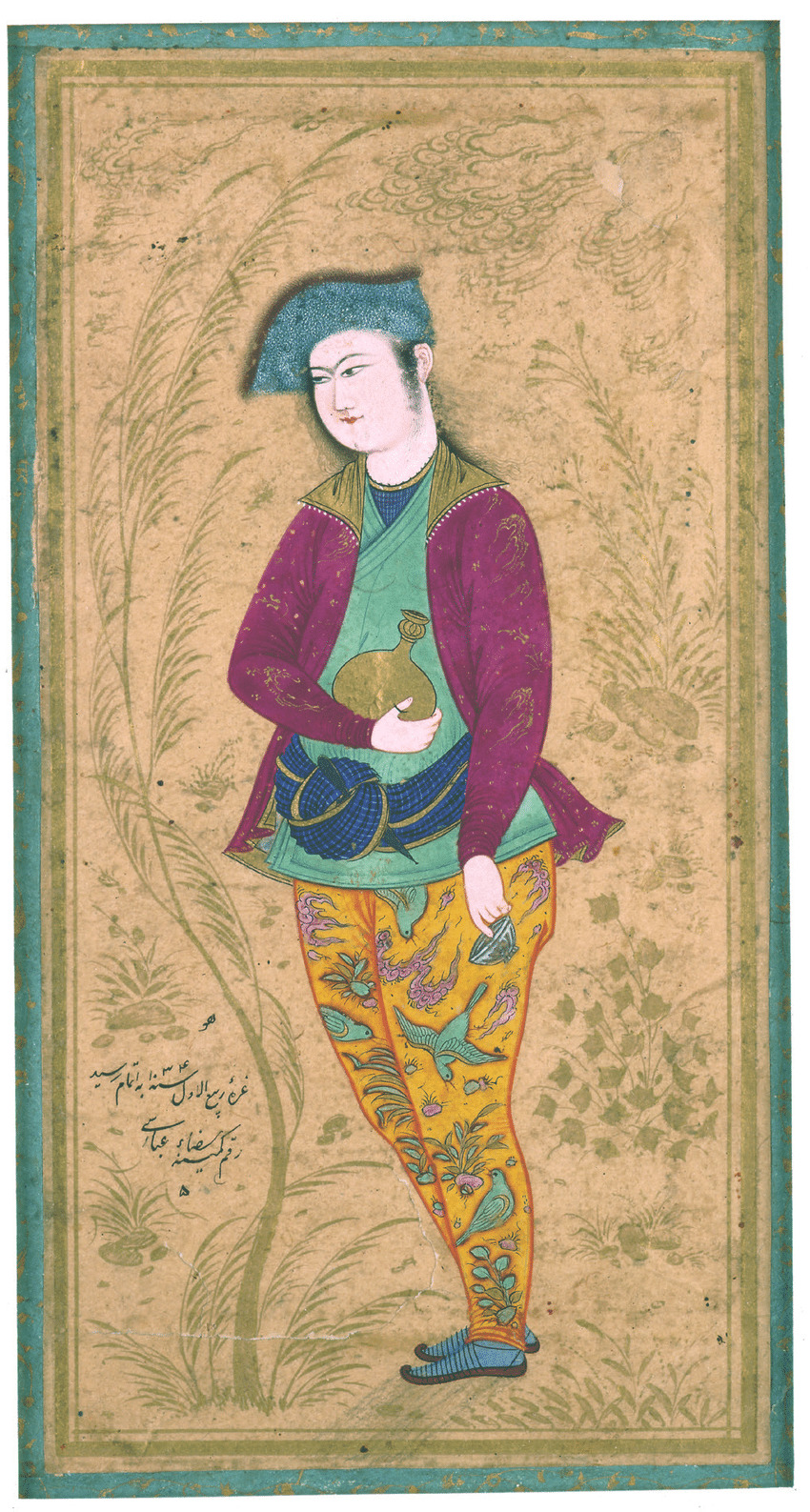

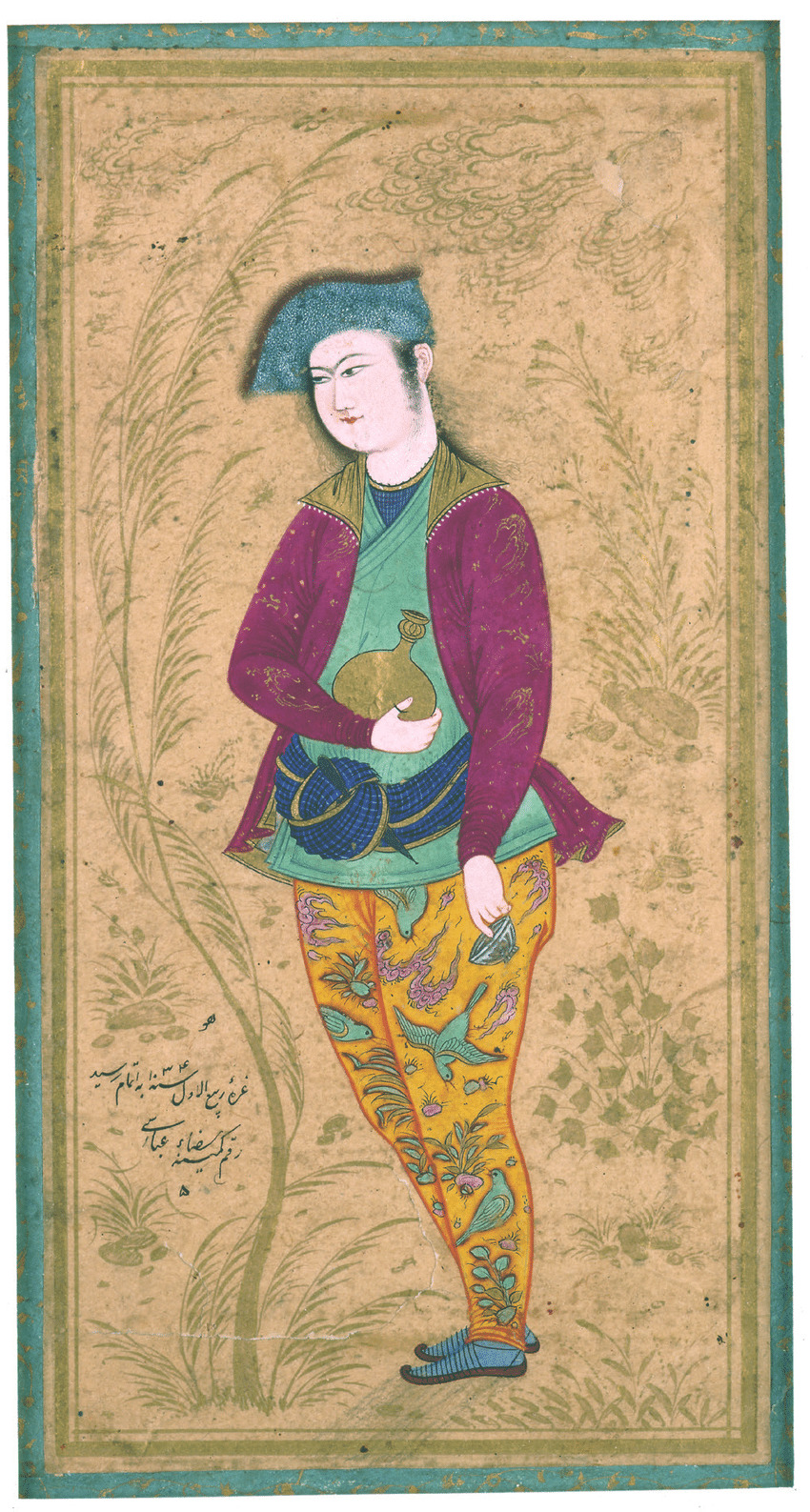

Standing Youth with a Cup and Pitcher, by Reza Abbasi

Alice Taylor considers Reza Abbasi a master of single-page (takhteh) painting and regards him as a central figure in the development of a new style of painting at the court of Shah Abbas I. Some defining features of Reza Abbasi’s unique artistic style include: Delicate, serene figures that lean slightly forward with gazes directed outside the frame, often appearing dreamy, usually holding a branch of flowers. He used soft, poetic, and beautiful colors that enhanced the lyrical quality of the composition.. Graceful and harmonious body movements executed with an innovative approach. Exquisite brushwork that is entirely delicate, fluid, and masterful. Muted, poetic color palette combined with large, voluminous turbans and earthy-toned backgrounds, featuring elements like weeping willow trees, fine clouds, flower bushes, and fruit or drink vessels. Some of these characteristics were already common among Reza Abbasi’s teachers at Ibrahim Mirza’s court in Mashhad, but they reached full maturity and refinement in his own design style. His spontaneous, strong, flowing, and rhythmically balanced brushwork in most of his works reflects the unique skill, power, and mastery of his hand.

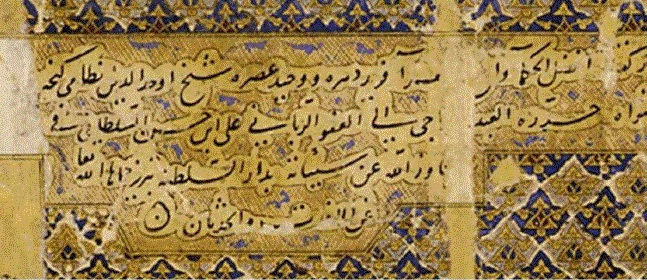

In Reza Abbasi’s painting style, the various elements and factors are arranged with such skill that they captivate viewers, while simultaneously embodying simplicity, depth, visual value, and aesthetic harmony. The signature of Reza Abbasi in his later works—roughly from 1020 AH until the end of his life—has a distinctive style. In these works, he begins his signature with the word "هو" (“Hu”) written in broken Nasta‘liq calligraphy, and, in addition to noting the year, month, day, and sometimes the location of the painting, he continues with the phrase "کمینه رضا عباسی" (“minimum of Reza Abbasi”). Finally, he writes the number five as a counterpart to the word "هو" at the bottom. This unique form of signing is specific to Reza Abbasi and is characteristic of his later period.

In conclusion, Reza Abbasi should be regarded as one of the geniuses of Persian miniature painting, who shone particularly brightly during the reign of Shah Abbas I, who honored him with the title “Abbasi.” This distinguished artist founded a new school of painting known as the “Isfahan School.” In this school, the traditional methods of Iranian painters—used to create spatial depth and arrange crowded compositions—gave way to the depiction of single-figure and solitary compositions adorned with opulent attire. Abbasi also went beyond illustrating the margins of literary manuscripts, introducing innovative designs and expanding the scope of Persian painting. Within Shah Abbas’s royal library, Abbasi primarily created single- and double-page paintings. His distinctive style is characterized by simple spatial arrangements, pleasing circular lines, minimal use of color, and occasionally meticulous detailing of clothing textures, hair, and beards. These artistic qualities influenced many subsequent painters and solidified his lasting legacy in Persian art.

The painting “Young Portuguese” by Reza Abbasi.

Some of the most important works of this talented Iranian artist include: Lovers, Bird Study, Man in a Fur Cloak, Old Man and Young Man, Youth Falling from a Tree, Seated Man in the Desert, Sheikh in a Barren Land, Luti and Antarash, Pilgrim from Mashhad, Seated Dervish Holding a Flower, Thief, Poet and Dogs, Majnun, Dog and Two Travelers, Villager and Skinny Horse, Young Portuguese, White-eared Nightingale, and more.

| Name | Reza Abbasi: The Pinnacle of the Isfahan School of Persian Miniature Painting |

| Country | Iran |

Choose blindless

Red blindless Green blindless Blue blindless Red hard to see Green hard to see Blue hard to see Monochrome Special MonochromeFont size change:

Change word spacing:

Change line height:

Change mouse type:

(7)_1_1.jpg)

.jpg)