Relief sculpture, façade of the Iranian Embassy in Abu Dhabi, 1991

Seyed Mohammad Ehsai: The Painter with a Refined Sense for Words

Seyed Mohammad Ehsai: The Painter with a Refined Sense for Words

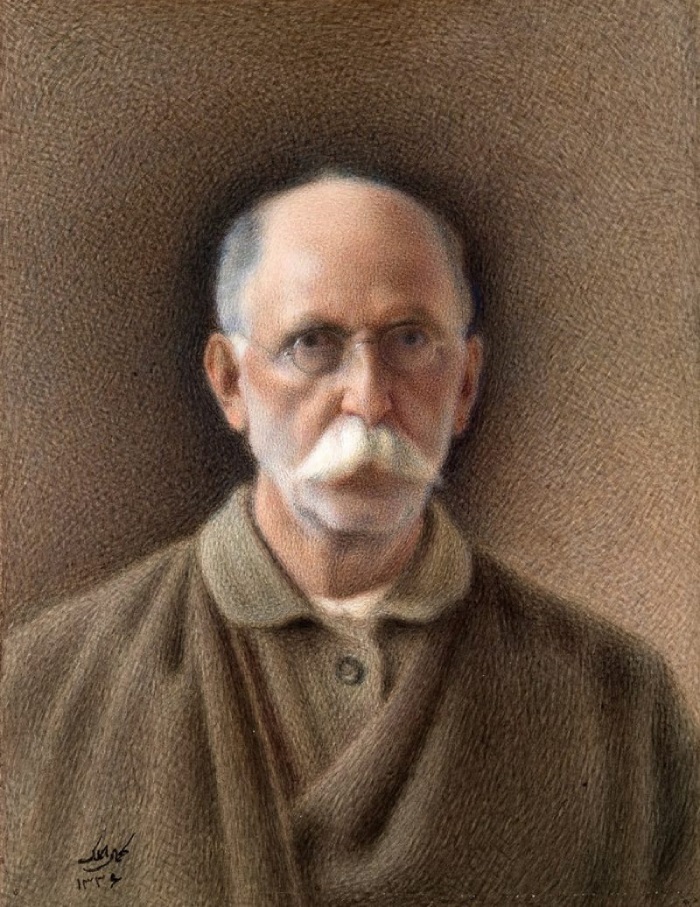

Seyed Mohammad Ehsaei, a renowned artist in Naqqashi-Khat (calligraphic painting), was born in 1939 (1318 SH) in Qazvin . In 1966, he entered the University of Tehran to study fine arts and traditional calligraphy, graduating from the Faculty of Fine Arts. Ehsaei began his professional career collaborating with a youth magazine and later joined the School Textbook Organization. Initially, he worked on book layout and design in this organization, then advanced to become the head of the graphic studio. Before long, he continued his work as the art expert for the visual arts textbooks used in the three-year guidance school program (middle school). The experiences he gained through collaboration with the Pars Institute and interaction with other graphic designers brought him closer to graphic art as a painter and calligrapher. Gradually, his presence in the field of graphic design—particularly in letter form design (huruf-negari) and aesthetic experimentation with Persian and Islamic scripts—became more prominent than his activities in painting. Due to this extensive experience in graphic design, Ehsaei played a significant role in establishing the graphic design program at the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Tehran.

Seyed Mohammad Ehsaei: Master Calligrapher

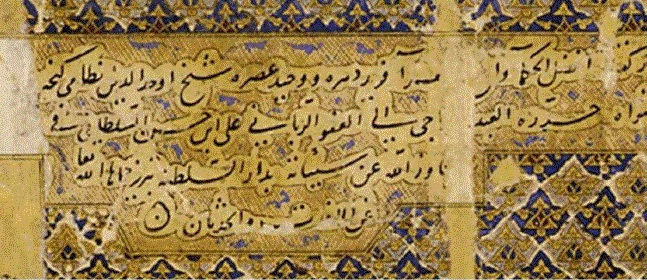

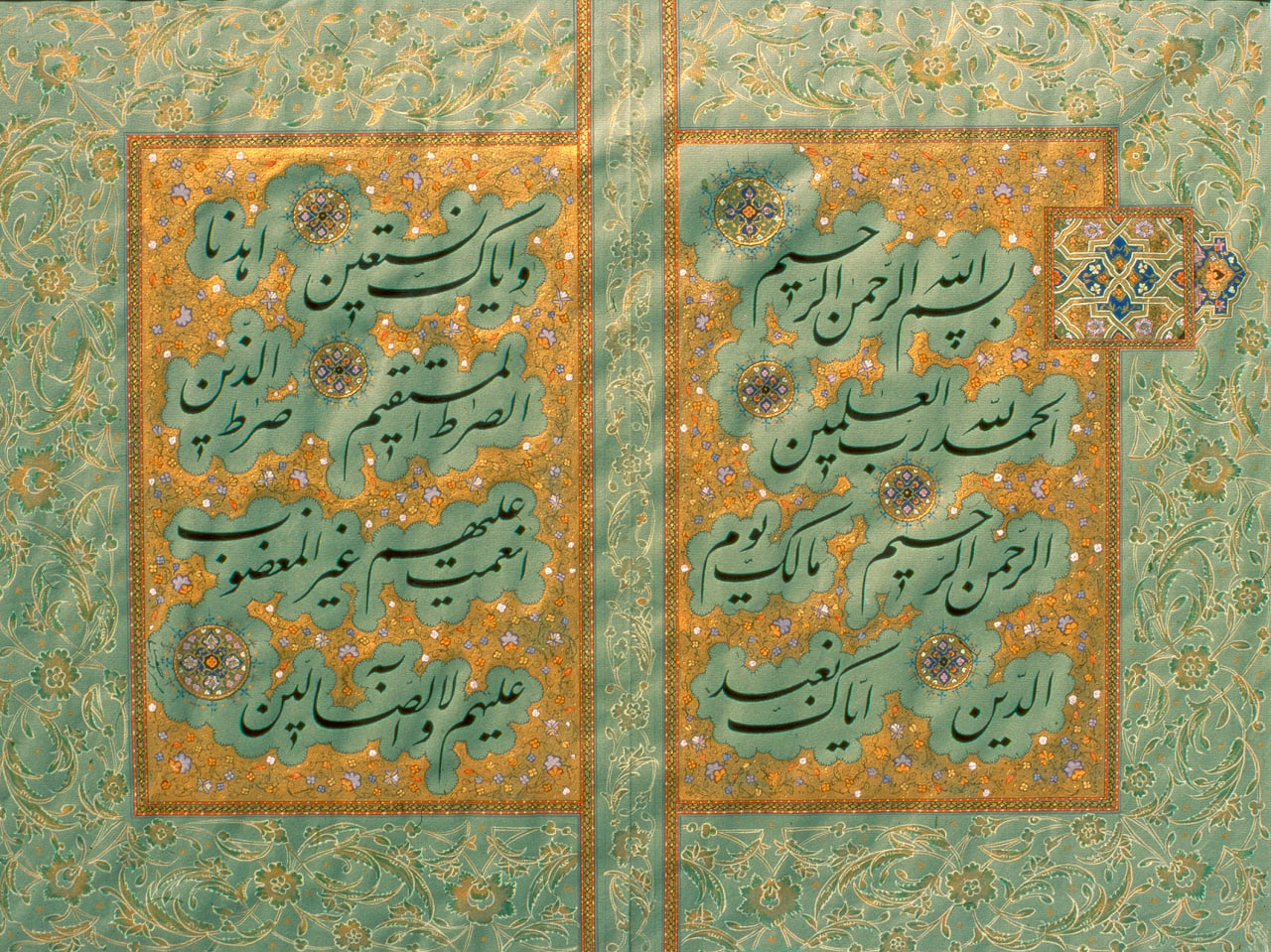

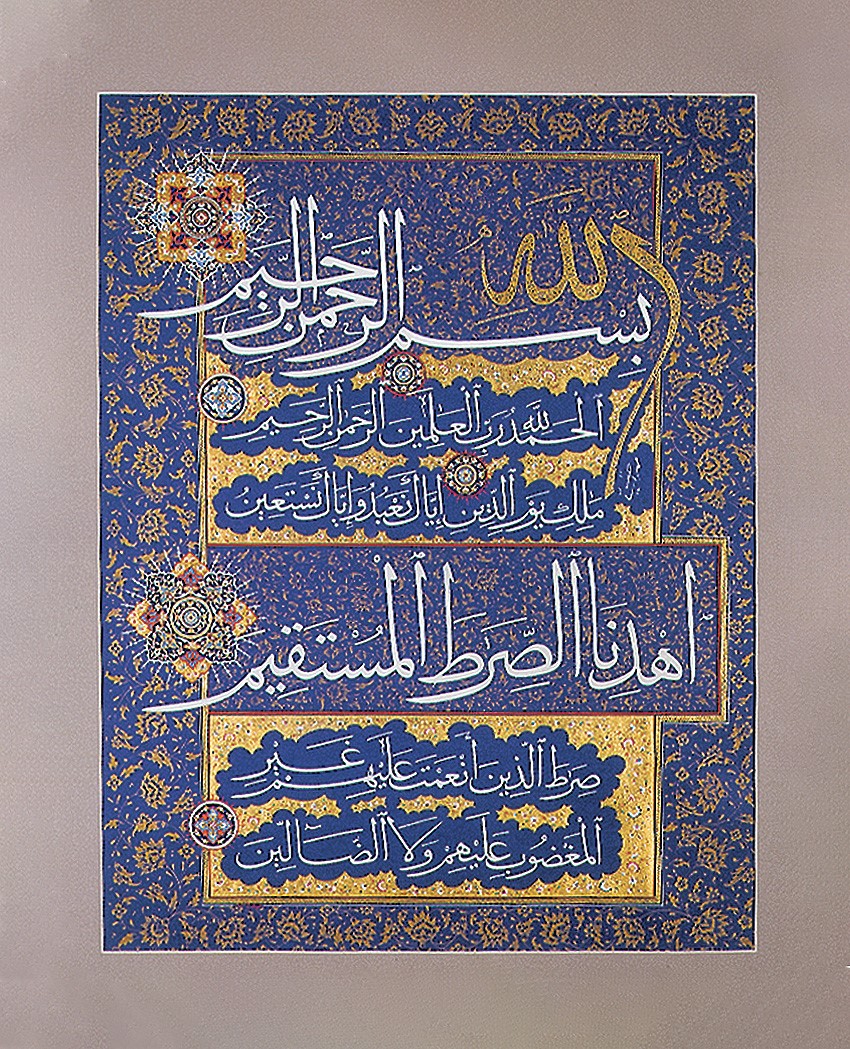

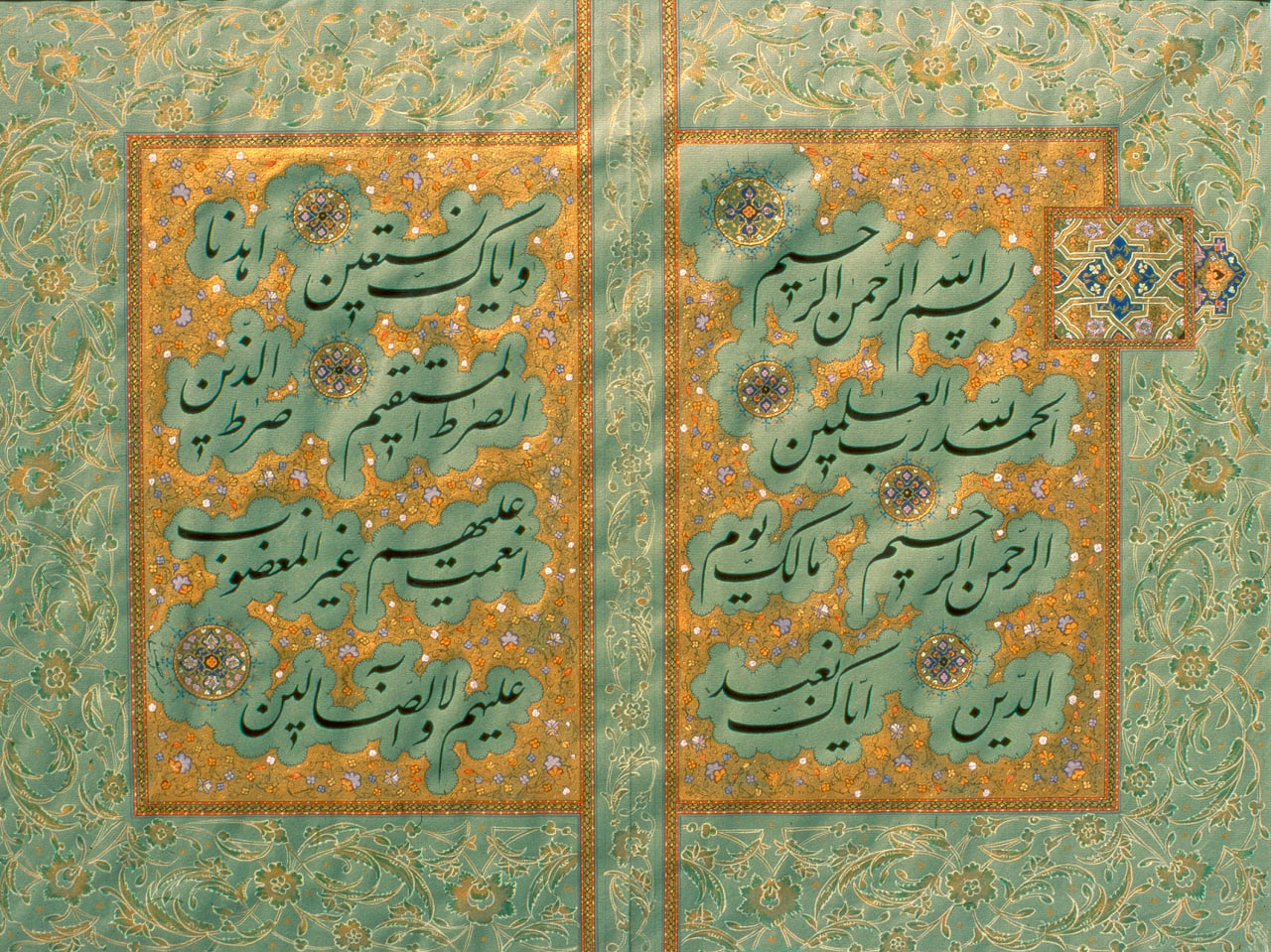

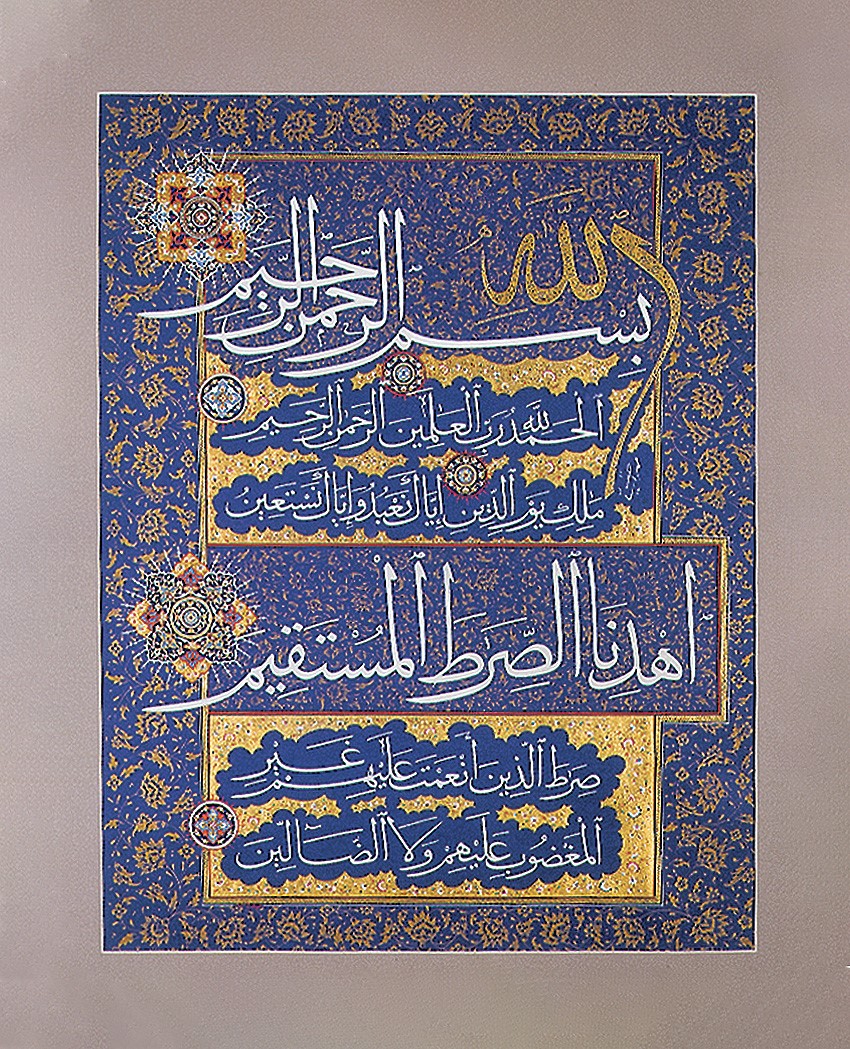

Seyed Mohammad Ehsaei, as he himself has acknowledged, began his artistic journey in the field of calligraphy by copying the works of Mir Emad and Emad al-Ketab. He later studied under Master Hassan Mirkhani and became deeply drawn to inscriptions and the expressive qualities of Thuluth, Reyhan, and Mohaqqeq scripts. Although he briefly studied Nastaʿlīq script under Seyed Hossein Mirkhani, his more serious reference point in calligraphy remains Mir Emad, with a stronger focus on Mirza Gholamreza Esfahani and the calligraphic style of the late Qajar period.

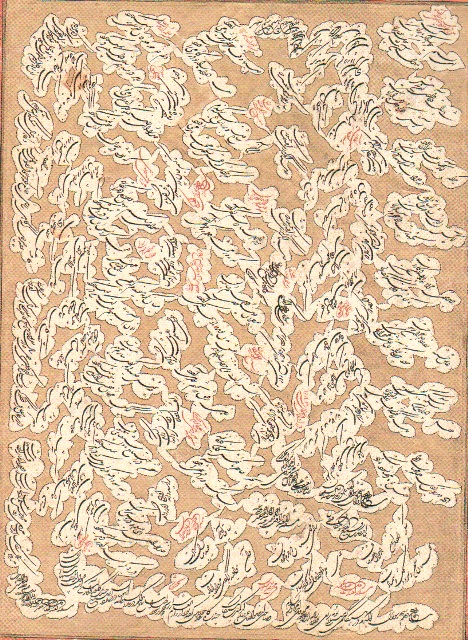

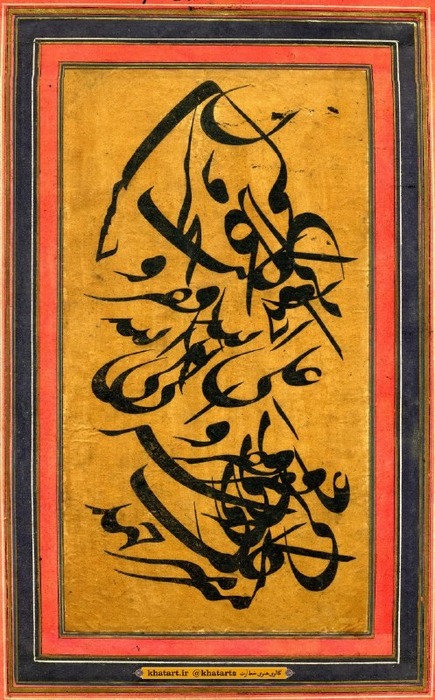

"Eternal Alphabet (Alefbā-ye Azalī)", 1975

It should be noted that despite all of Ehsaei’s efforts to follow the style of Mirza and certain other Qajar-era calligraphers, his style in nastaliq is by no means free from the influence of Emad al-Ketab. From an aesthetic point of view, Emad al-Ketab’s calligraphy possesses a reserved and modest character, influenced by the ketabat (book-writing) tradition. This stands in direct contrast to the passionate spontaneity and informality of Mirza Gholamreza Esfahani’s work, which stems from the siah-mashq (black practice sheet) tradition. This sense of restraint is quite evident in Ehsaei calligraphy as well, and it seems to represent a personal dimension that has also permeated his overall approach to calligraphy in the mohaqqeq, reiḥan, and thuluth scripts. With remarkable mastery and self-confidence, Ehsaei largely taught himself and became proficient in numerous calligraphic styles, without direct mentorship from a master. He had a deep understanding of the traditional rules and principles of calligraphy and was equally skilled in the graphic techniques and craftsmanship associated with them. Thus, guided by a distinctive sensibility and an innovative spirit rooted in the Persian calligraphic tradition, he experimented across many styles of calligraphy and produced flawless works. His siah-mashqs, chelipas (diagonal compositions), and other calligraphic panels stand as clear testimony to this claim.

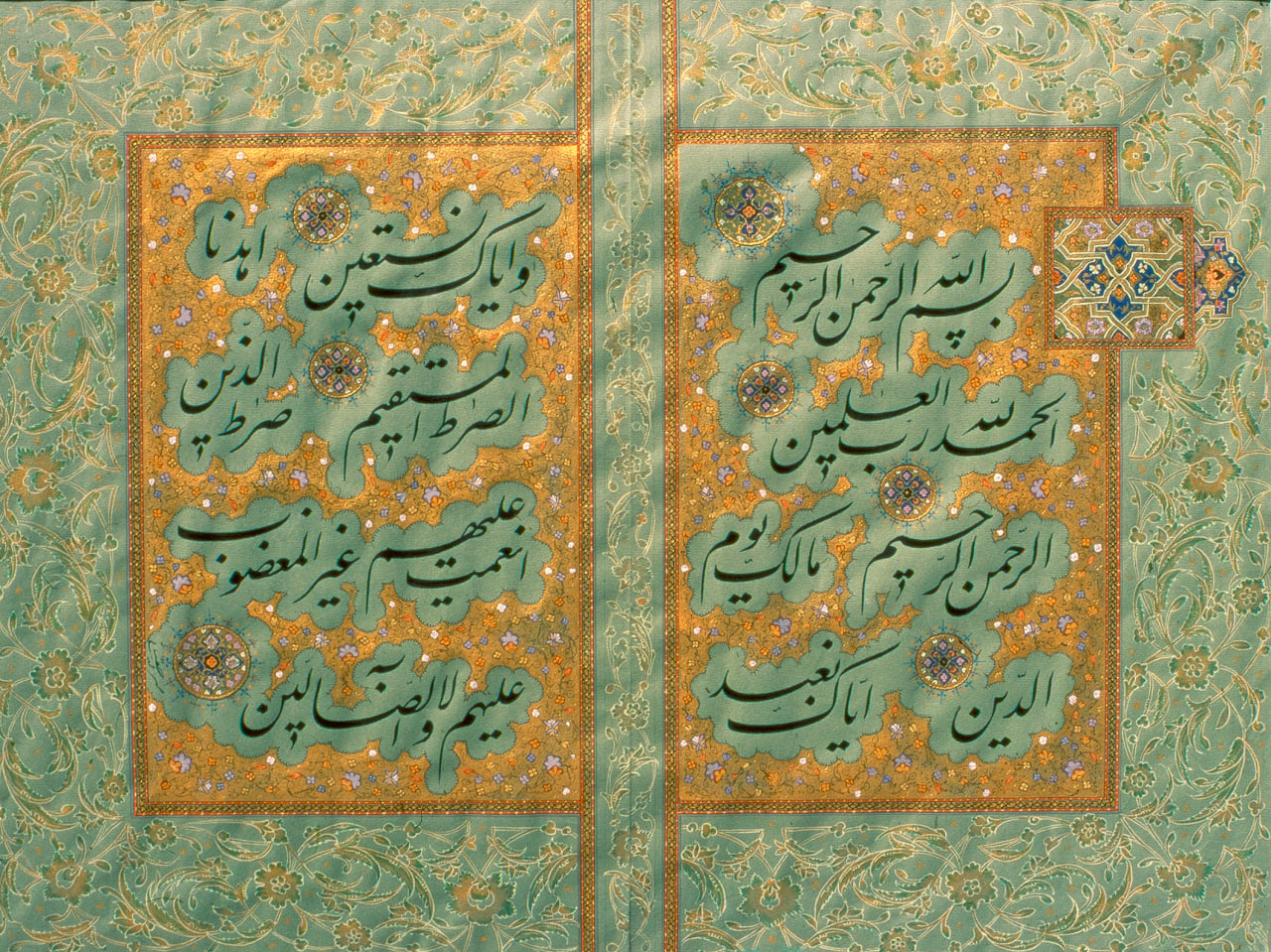

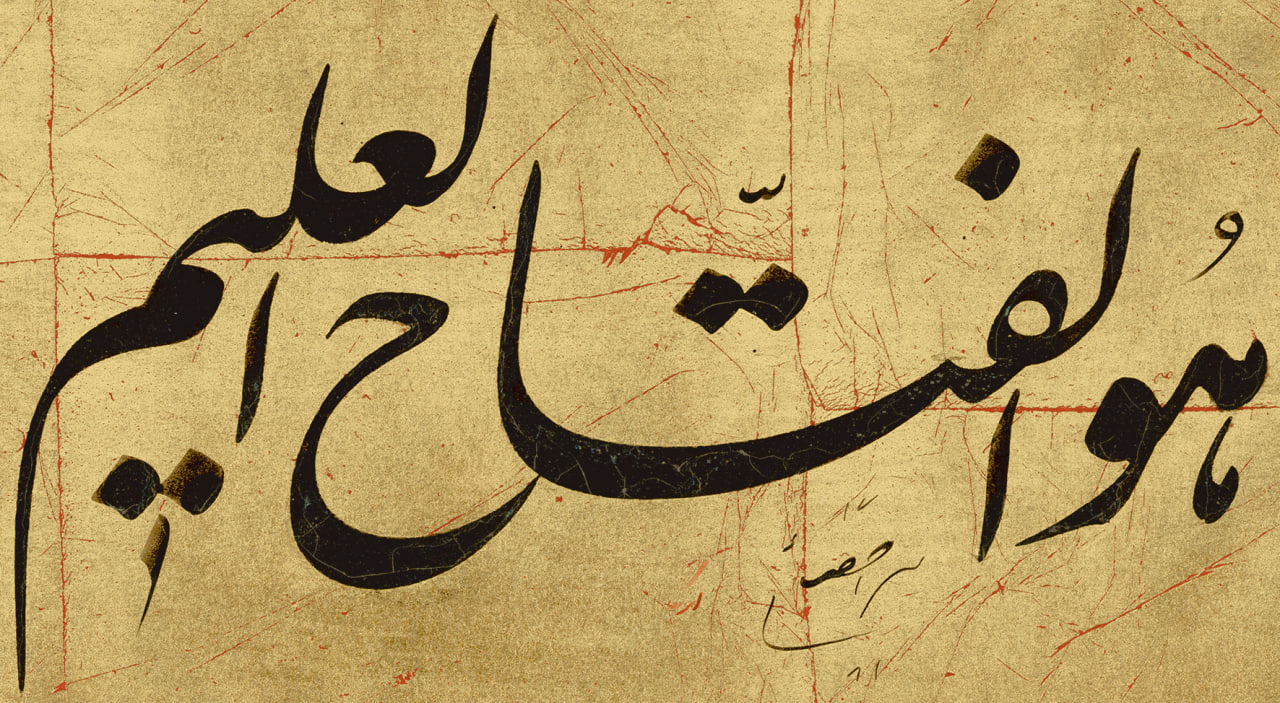

Ehsaei also paid full attention to the conceptual essence of calligraphy in relation to his chosen format. He is an artist emerging from tradition who also mastered modern graphic art, intertwining the discourse and craftsmanship of classical calligraphy with the modern visual language of art. Although Ehsaei does not identify himself as one of the so-called Saqqa-khaneh artists in Iran, his art and aesthetic discourse affirm his affinity with that movement. Ehsaei was among the first artists to bring calligraphic painting (naqashi-khat) from the traditional into the modern era. He organized his calligraphic paintings in the same disciplined manner as his classical works, adhering to all the principles and rules of calligraphy. One of the most striking characteristics of Ehsaei’s art is his inclination toward liberation. In a broad sense, it can be said that Seyed Mohammad Ehsaei, in his classical calligraphy, sought to move from form to formlessness—from structure to expression. Beyond the Persian scripts such as nastaliq and shekasteh, Ehsaei also devoted special attention to thuluth, mohaqqeq, and reiḥan. In these scripts as well, he demonstrated a profound understanding of the history of calligraphy and achieved a unique, synthesizing style.

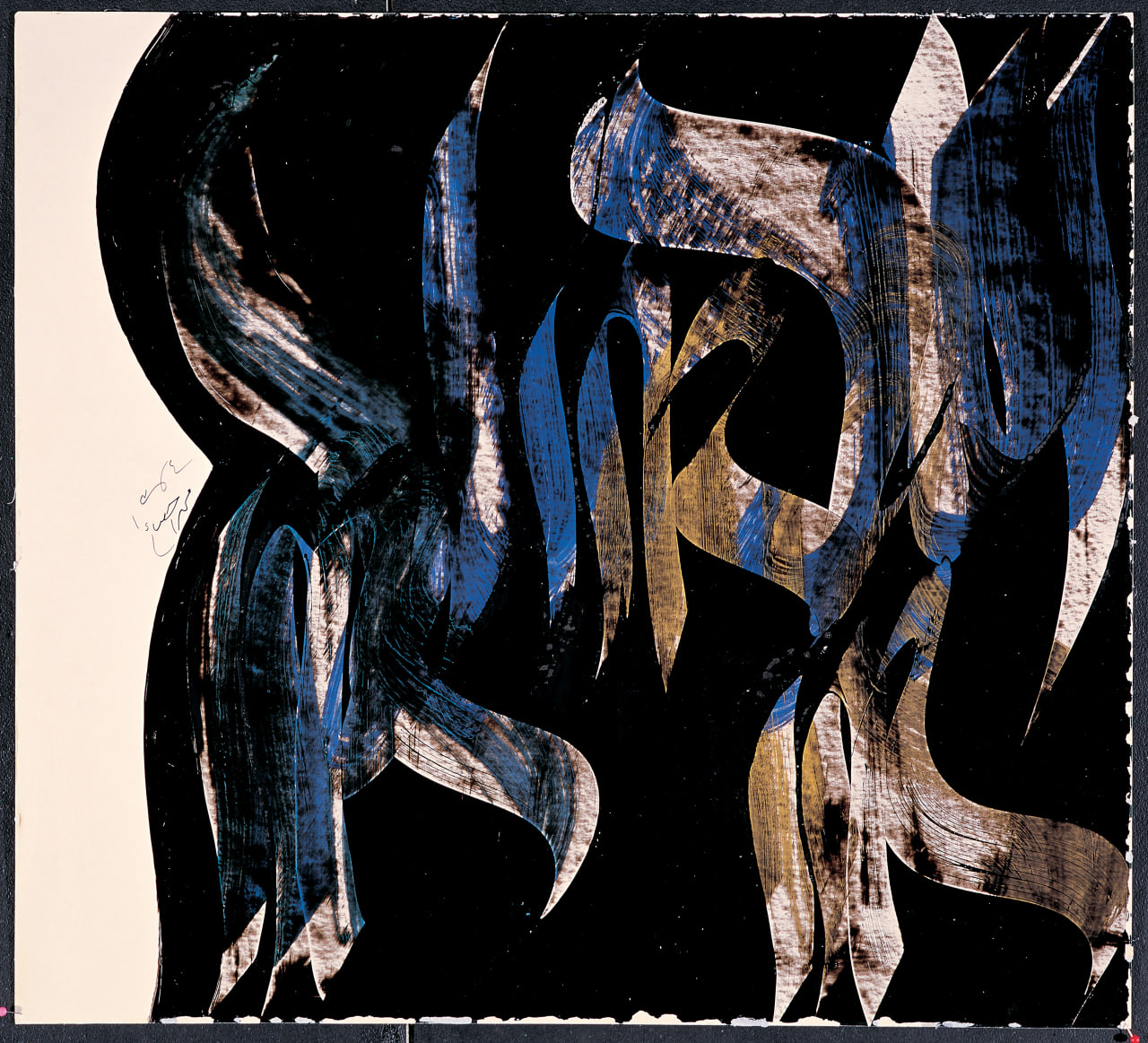

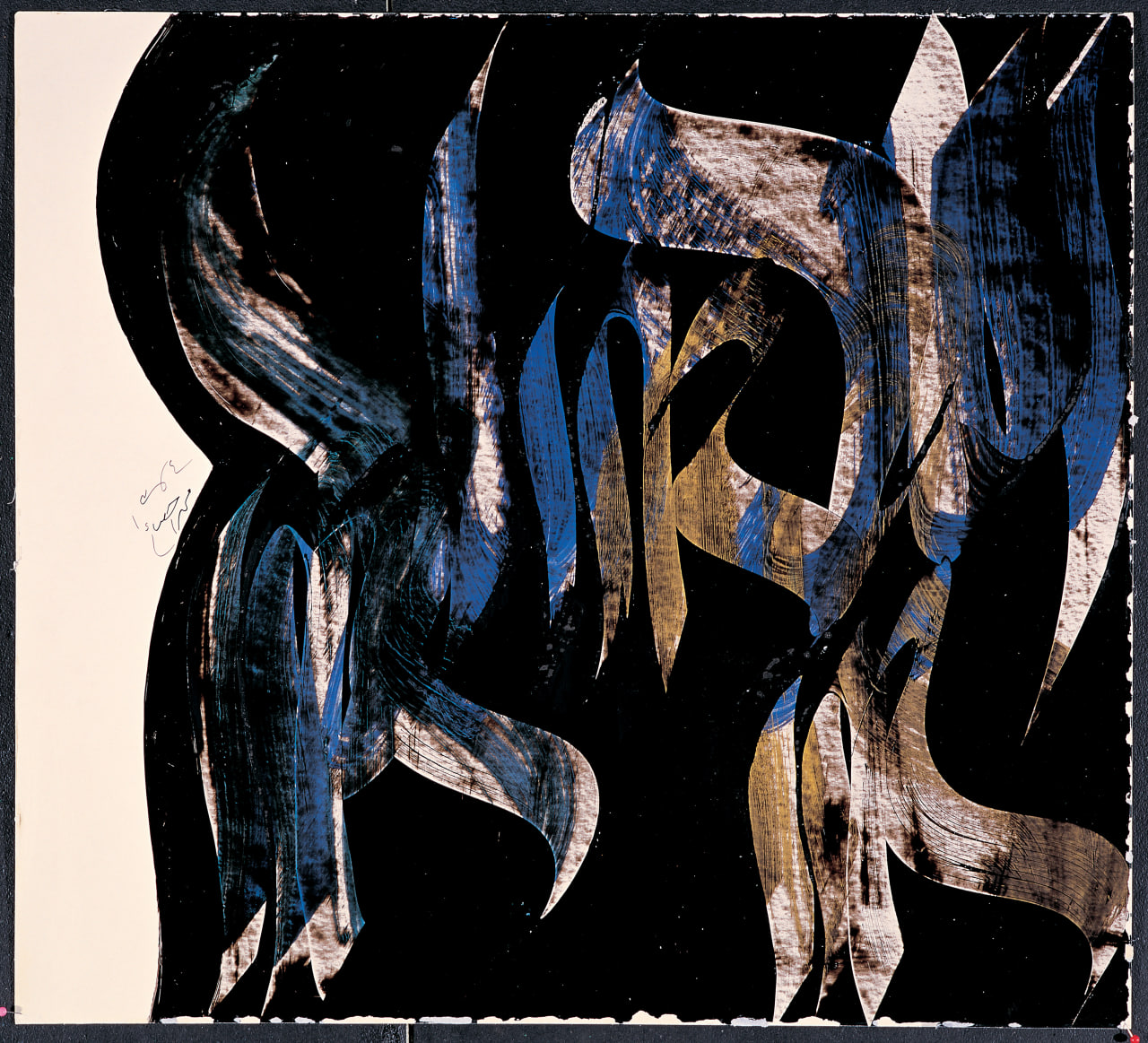

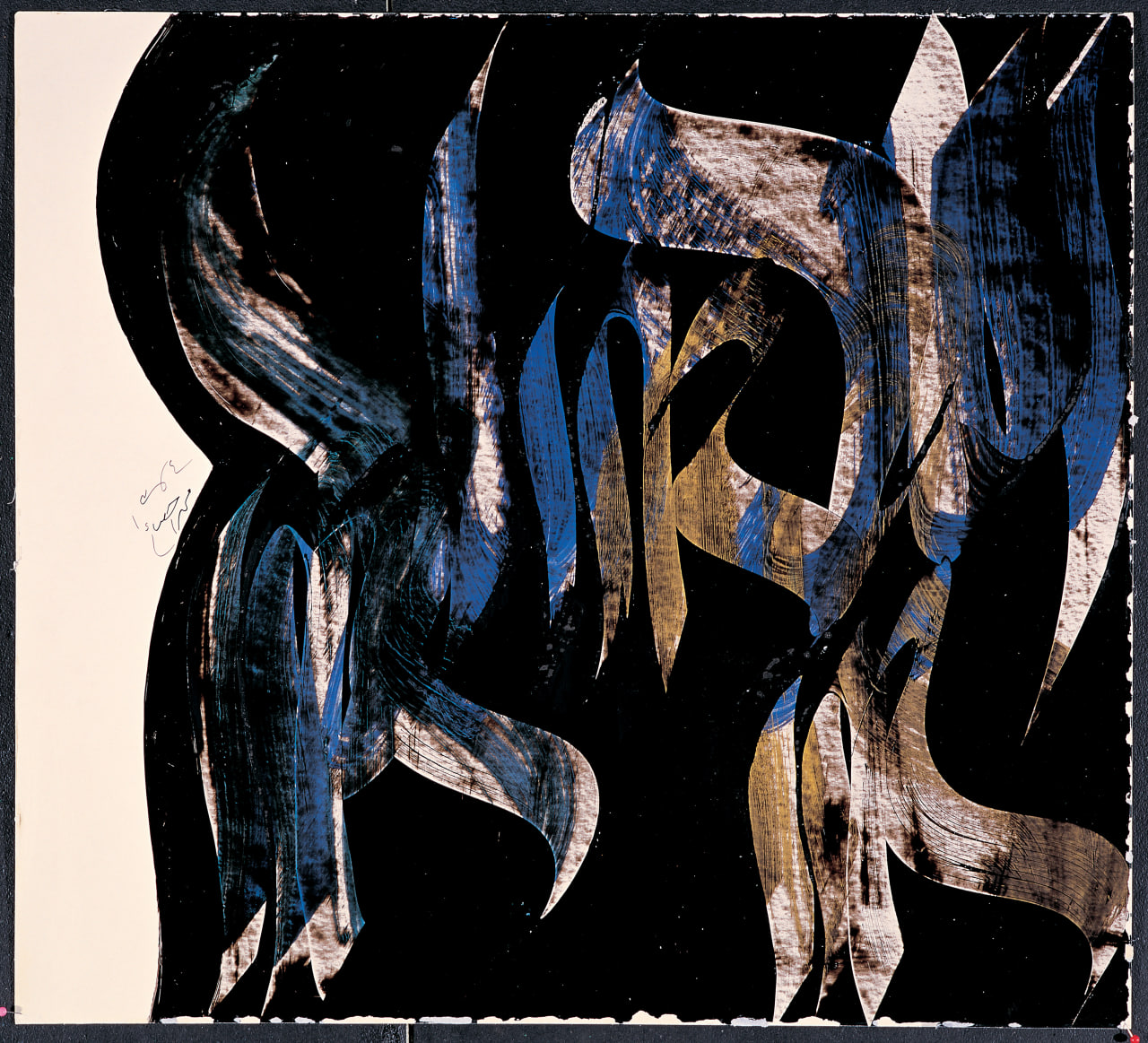

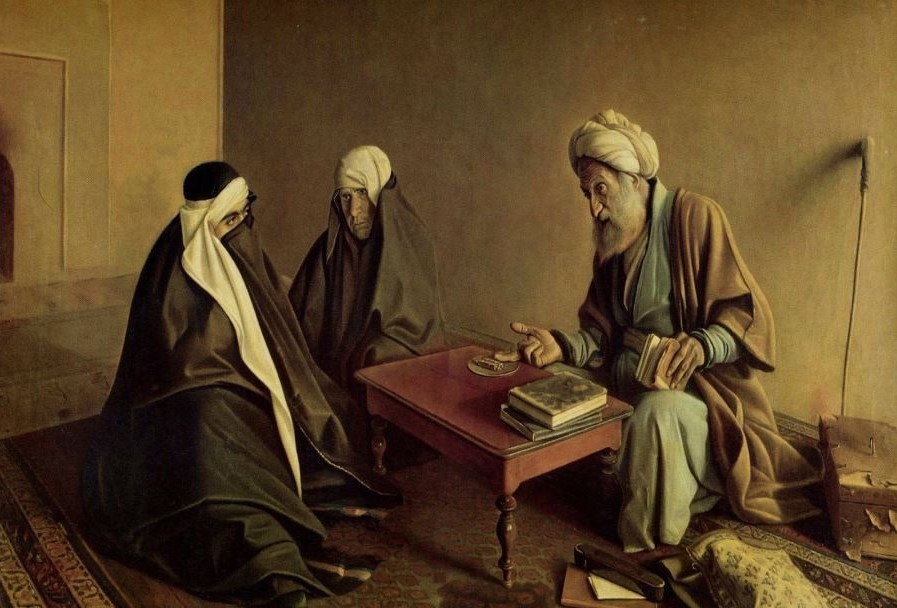

Echo of the Word,” oil on canvas, 1988, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art

Echo of the Word,” oil on canvas, 1988, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art

In relation to the Thuluth script, it should be said that Ehsaei is not particularly mannerist in his approach; without a doubt, he can be described as a pragmatic reviver of the Aqlām-e Setteh (the six classical styles of Islamic calligraphy). To enrich his artistic expression, he drew upon the entire visual and structural potential of Islamic calligraphy. He made use of various scripts, formats, and materials, thereby creating a truly distinctive form of art.. Ehsaei mastered multiple calligraphic styles, and his approach to contemporary calligraphy was largely self-taught. He also experimented with less conventional compositions within traditional forms, such as Chelipa (diagonal compositions) and Ketabat ( manuscript writing). However, Seyed Mohammad Ehsaei’s greatest fame stems from the unique innovation he introduced to Iranian Naqqashi-Khat (calligraphic painting). He is widely recognized as a pioneer in using words as a medium for personal artistic expression; his 1968 work ‘Knot of Khayyam’ (Gerehaye Khayyam) is often cited as a landmark piece. A skilled calligrapher by training, Ehsaei considered himself closer to the traditions, scripts, and essence of calligraphy than to the painters of the Saqqa-khaneh movement. He attributed this closeness to his faithfulness to the authentic traditions of calligraphy and his connection to the true form of letters. In this sense, Ehsaei’s artistic journey was a movement from calligraphy toward painting, integrating the visual and conceptual elements of painting into his calligraphic works. This approach,His movement, which emerged a few years after the Saqqa-khaneh painters, was initially met with resistance but later inspired a wave of imitation among calligraphers. Ehsai demonstrated greater perseverance and dedication than any of his contemporaries in advancing and defining Naqqashi-Khat as a distinct artistic discipline. To this day, he continues to gain recognition through his diverse and innovative works.

“Surah Al-Hamd,” Nasta‘liq script, 1998

Ehsaei the Painter

Ehsaei’s entry into the circle of painters and graphic artists took place in the early 1960s at the Pars Institute, where he became acquainted with the new environment and the field of modern art. Yet, although Ehsaei created modern works, However, his mindset never fully embraced modernism in the strict sense of the term. This marks one of the key distinctions between him and certain other Iranian modernists. Ehsaei was a spiritual seeker, consistently bound to meaning — but a meaning rooted in traditional spirituality, not the abstract mysticism that preoccupied theorists of abstract art. One of the most important aspects of Ehsaei's modern works — which should be evaluated within the context of Iranian modern painting — is the fluid presence of geometry, a strong and dynamic element that seems to keep Ehsaei grounded as a calligrapher. The influence of classical calligraphy in his paintings can thus be interpreted from this perspective. The geometry in Ehsaei’s works is alive and mobile, finding room to move within a firm structure. Even when painting, Ehsaei remains a calligrapher experimenting with new experiences. His paintings should be understood as a continuation of his calligraphic consciousness, for he never breaks free from the dominance of letters and words. In some of his works, his technique approaches that of Chinese calligraphy. The letters in Ehsaei’s art are not reduced to mere visual elements — they constitute the very essence of the work. Although his paintings make effective use of color and form to enhance expression and completeness — qualities worthy of contemplation in their own right — these are not the intrinsic elements of his art. Undoubtedly, Ehsaei’s thoughtful use of color and form has played a vital role in giving his works a transcultural identity, making his artistic language more accessible to a global audience.

“Flower, Hyacinth, Nowruz,” oil on canvas, 2015

A Reflection on Ehsaei’s Artistic Style and Approach

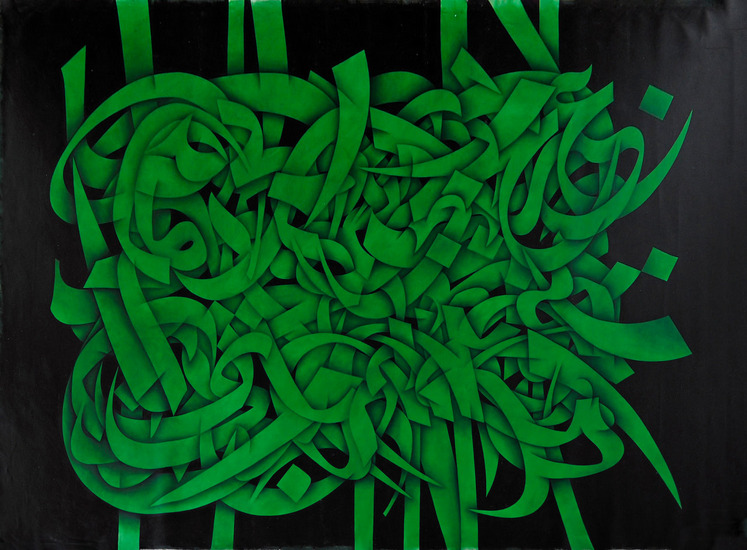

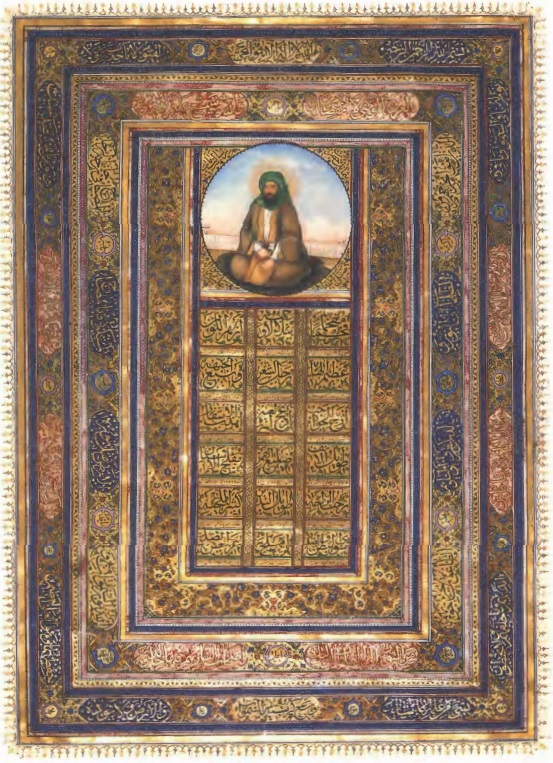

The works of Seyed Mohammad Ehsaei can be broadly divided into two main tendencies: traditional calligraphy and modern calligraphic expression. He is an artist who spent many years training in calligraphy within the traditional educational system, yet his artistic maturity and creative flourishing occurred during the modern art period. In creating traditional works, Ehsaei shows no inferiority to the great masters before him, skillfully reviving many classical calligraphic forms. However, his art never stagnated in repetition; rather, it became the foundation for innovative works that invite the viewer into a world rich with the beauty and originality of Naqqashi-Khat (calligraphic painting). Throughout his artistic life, Ehsaei devoted a period to traditional calligraphy, producing works within its classical structures. After this phase, his artistic journey transitioned into a modern period, during which he began creating compositions resembling knots and interwoven clusters of letters. In these works, Ehsaei presented a creative structure of calligraphic painting, employing visual elements to convey the spiritual and semantic essence of words, letters, hadiths, Quranic verses, and similar sacred expressions. Beginning in 1975, Ehsaei produced canvases often centered on the divine name ‘Allah’ or the phrase ‘La ilaha illallah (“There is no god but God”). These works marked a significant evolution in his career, uniting spiritual meaning and modern visual expression within a uniquely Iranian artistic language.

.

“La ilaha illallah” (There is no god but God), offset print.

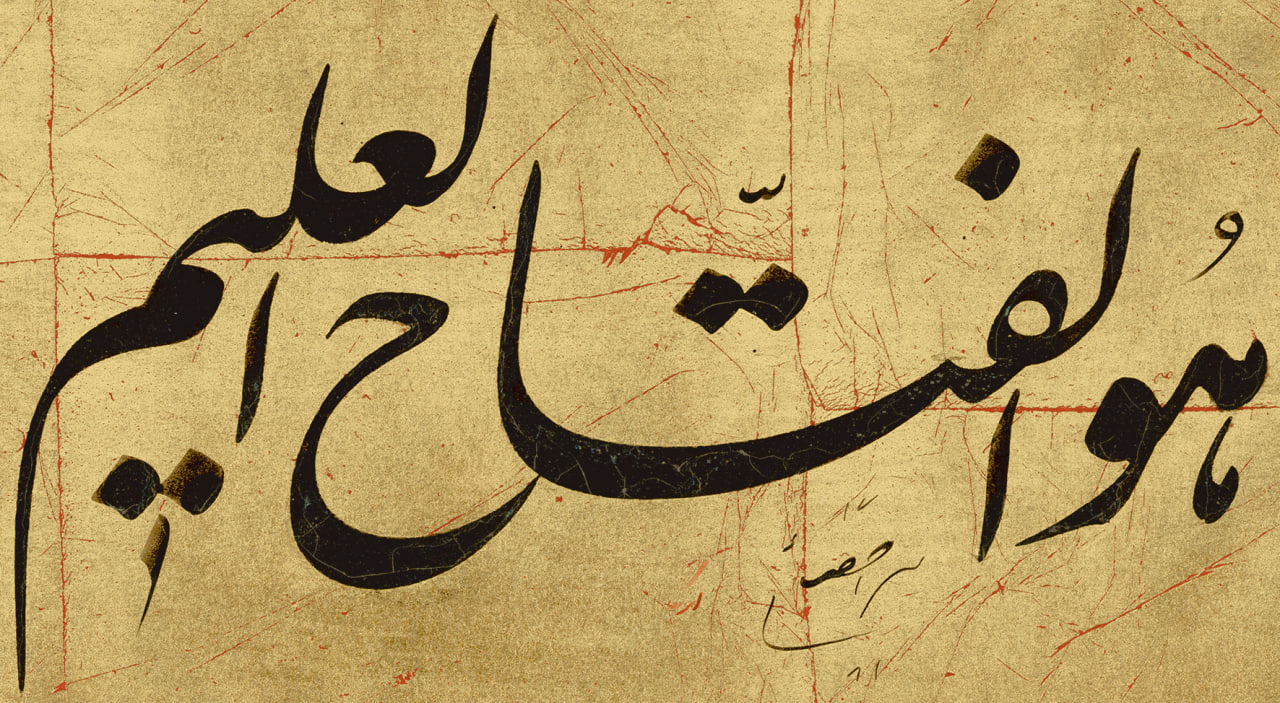

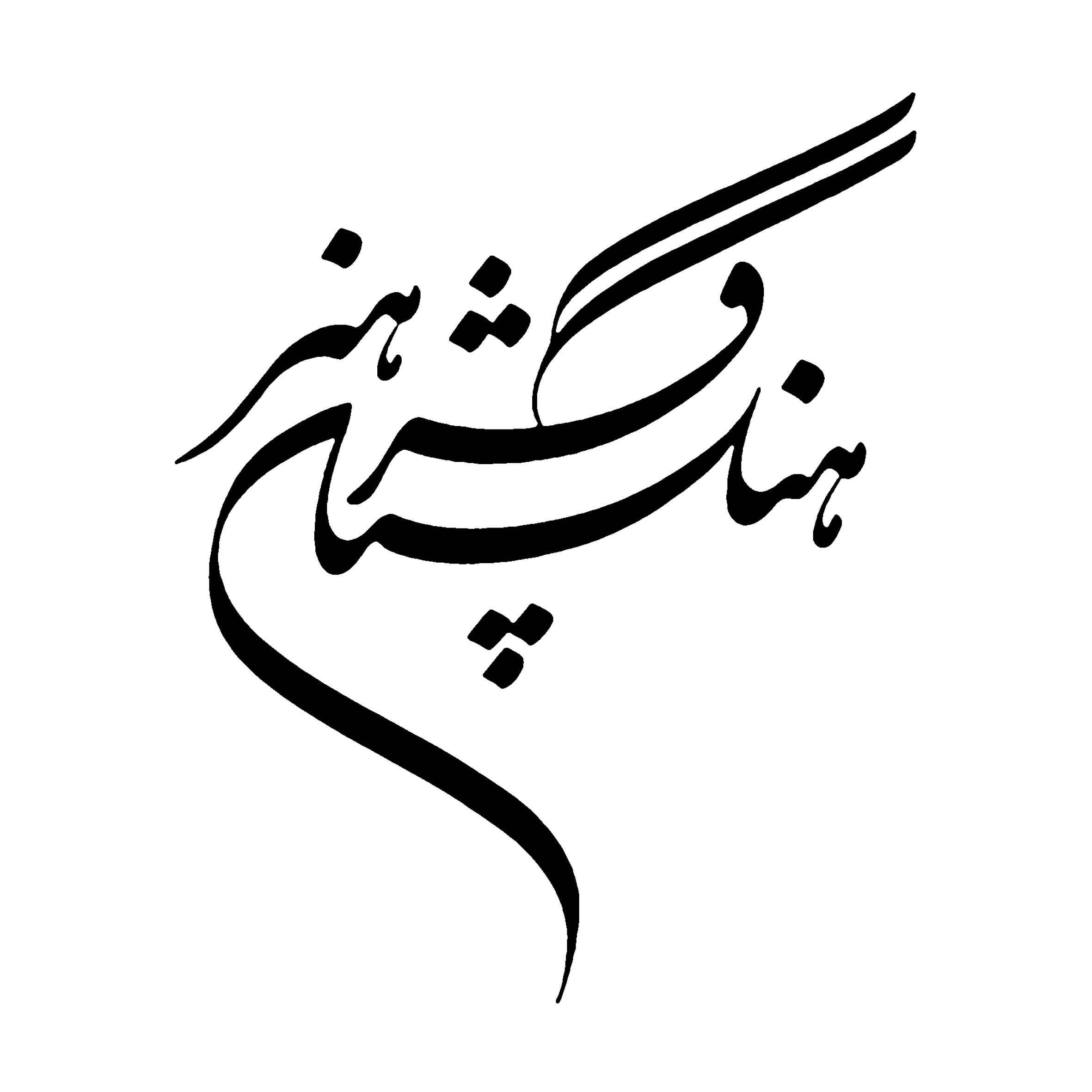

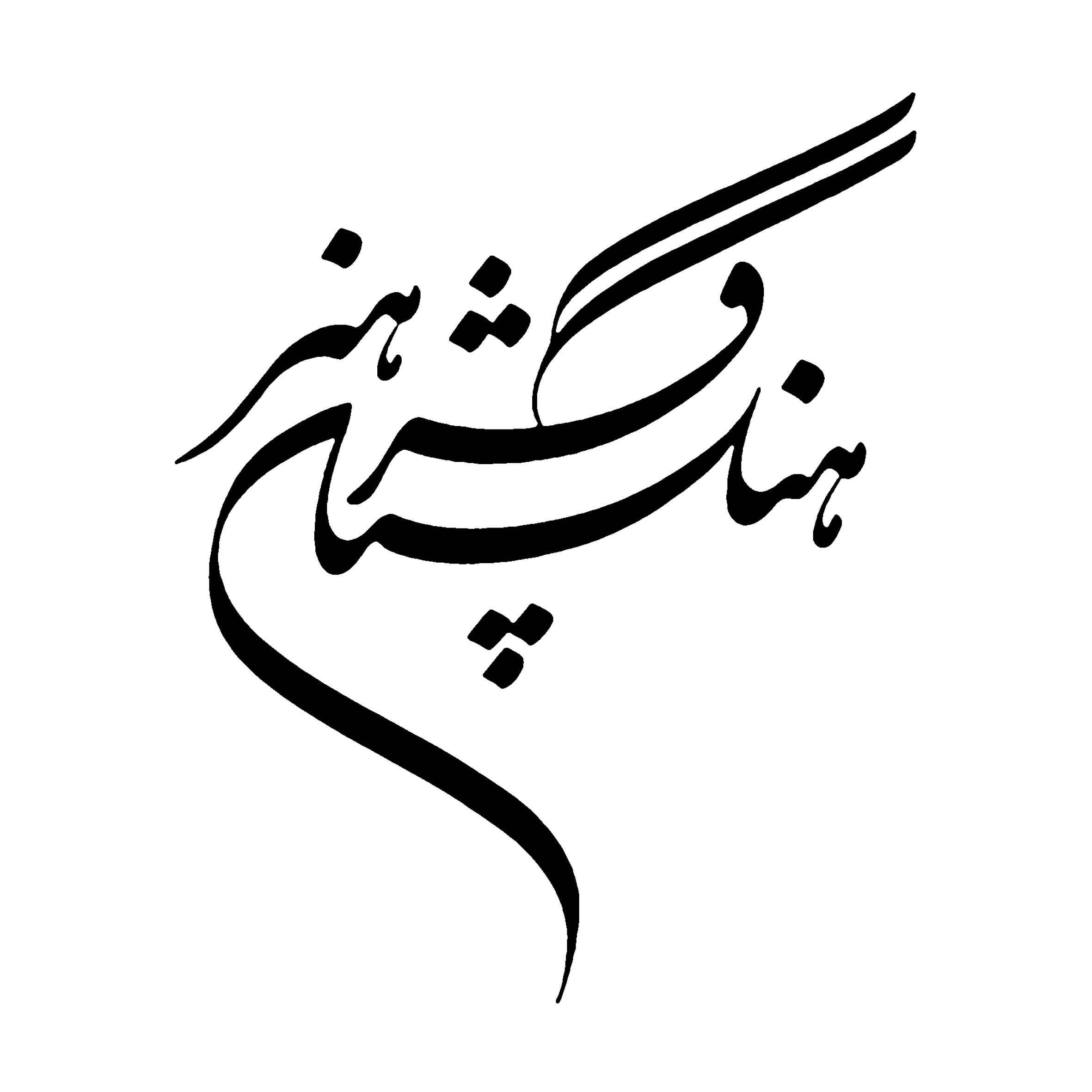

According to the artist, these works function as a visual zikr of “Allah” and serve as an expression of Islamic mysticism and Sufism. Ehsaei has created these works — commonly referred to as the “Allah” series — multiple times. In one of his latest achievements, he completely eliminated color, exploring whiteness on whiteness and blackness on blackness, both of which are manifestations of light, thereby creating a novel visual composition. This approach has also become known as the “Eternal Alphabet” (Alfabaye Azali). In the “Eternal Alphabet” series, through the dance of letters and the creative use of positive and negative spaces inherent in Thuluth and Reyhan scripts, Ehsaei reflects spiritual concepts through calligraphic forms. This collection can be considered a visual dhikr, in which conventional calligraphic rules and traditional geometric frameworks are deliberately set aside. In creating the series, Ehsaei focused on writing and structuring the divine word “Allah”, channeling the energy and passion of his pen onto the canvas and thereby recording varied yet interconnected experiences across different textures. “The series features rotational compositions of the sacred word Allah, as well as single-word, dual-word, and four-word arrangements, rendered on diverse backgrounds often dominated by black hues. These works reflect Ehsaei’s engagement with modern art while remaining deeply rooted in traditional concepts. Leveraging his graphic design knowledge and experience, Ehsaei also achieved a logo-like clarity in the presentation of each piece within the “Eternal Alphabet” series. Initiated in the mid-1970s, he has continued this work into recent years, maintaining the same stylistic approach, consistently exploiting the Thuluth pen, whose rhythm and dynamism. Among his other notable innovative works are the logo designs for the Nahj al-Balagha Foundation, Niavaran Cultural Center, Academy of Arts, Organization for Textbooks, Iran Graphic Museum, as well as the titles of numerous Iranian newspapers over the past three decades.

Logo of the Academy of Arts, 1998

Seyed Mohammad Ehsai has participated in numerous solo and group exhibitions, both within Iran and abroad. He has participated in major international exhibitions, including the Venice Biennale (60th edition), the Annual Art Exhibition in Basel, and shows in Bologna, Hangzhou, and at the Asia Society in New York. Ehsaei’s work in graphic design carries a distinctly calligraphic quality. From posters to logos, all of his creations begin with letters and structural games, carefully composed, and ultimately serve a graphic function. By blending tradition with innovation, his works establish a strong connection with audiences, which may explain why they have consistently drawn attention in artistic circles. In addition to critical acclaim, Ehsaei has achieved considerable success in the art market, both in Iran and internationally. In April 2008, one of his works sold for $1,180,000 at the Christie’s International Modern and Contemporary Art Auction in Dubai. In subsequent auctions at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in London, Dubai, and Doha, his works sold for $650,000 and $500,000, respectively. In 2020, one of his works sold for 6 billion Iranian tomans at the Iran Contemporary Art Auction. Ehsaei has also created significant relief works, in which calligraphy and the creative manipulation of letters remain the central focus. His most famous and beloved relief is located in the auditorium of the Faculty of Theology at the University of Tehran, executed in 1977. This monumental piece uses letters and the interplay of words to visually convey the essence of Attar’s poetry in The Conference of the Birds, depicting the ascents and descents of the Simurgh. Another notable relief by Ehsaei is at the Iranian Embassy in Abu Dhabi, UAE, where the artistic approach is entirely different from the Tehran University piece. In this work, single-colored letters appear on a seemingly aged, geometric, and abstract background, yet the letters retain the narrative and shared qualities of traditional Iranian calligraphy, such as Thuluth and Mohaqqeq scripts with diacritics, captivating viewers with their elegance and harmony.

Ehsaei’s art can be classified as religious art, insofar as its aim is to evoke a spiritual response in the human soul and guide it toward transcendence and elevation. To understand the religious dimension and its transformation in Ehsaei’s works, it is important to note that religious faith has always been a fundamental premise in his artistic endeavors. With the aim of spiritual elevation and its inherent nature, there is always an impersonal element in the creation of religious art. One of the defining characteristics of this art is the submission of the self to divine power. In Ehsaei’s works, a deep and distinctive process unfolds in the act of creation, through which he approaches the divine essence of the Quranic word, conveying its message according to the capacity of each individual viewer.

Overview of Works

Among the notable works of Seyed Mohammad Ehsaei are: the “Eternal Alphabet” series, Surah Al-Hamd, Surah Yasin, Hu al-Fattah al-‘Alim, Hu wa al-Sami’ al-‘Alim, Hafez Asrar-e Elahi, Three Leaves of Love, That Heart Which You Have Seen, This Flower Comes from a Kindred Soul, O How We Are Not and the World Will Be, Whoever Keeps Faith with the Loyal, Good and Evil in Human Nature, The Foundation of Work Comes from Planning, At the Threshold of the Beloved, If One Can Submit, We Are Beggars of the Tavern of Love, In the Eyes of the Dawn, I Rejoice in That, O Lord, Make the End Auspicious, Since Nothing Exists from What Exists, Sit with Someone Who Knows the Heart, and many others.

Untitled, 2018

In 2023, Seyed Mohammad Ehsaei was recognized as a Living Human Treasure and officially registered in the national list of “Masters of Intangible Cultural Heritage.”

| Name | Seyed Mohammad Ehsai: The Painter with a Refined Sense for Words |

| Country | Iran |

| awards | International,National |

Choose blindless

Red blindless Green blindless Blue blindless Red hard to see Green hard to see Blue hard to see Monochrome Special MonochromeFont size change:

Change word spacing:

Change line height:

Change mouse type:

(7)_1_1.jpg)