Sleeping Two Figures on a Bed in the Presence of Others is a triptych by Francis Bacon and is considered one of his most important works. This piece, due to its homosexual theme, was displayed publicly only once after the Iranian Revolution. However, in 2004 (1383 SH), it was loaned to the Tate Museum in London for exhibition.

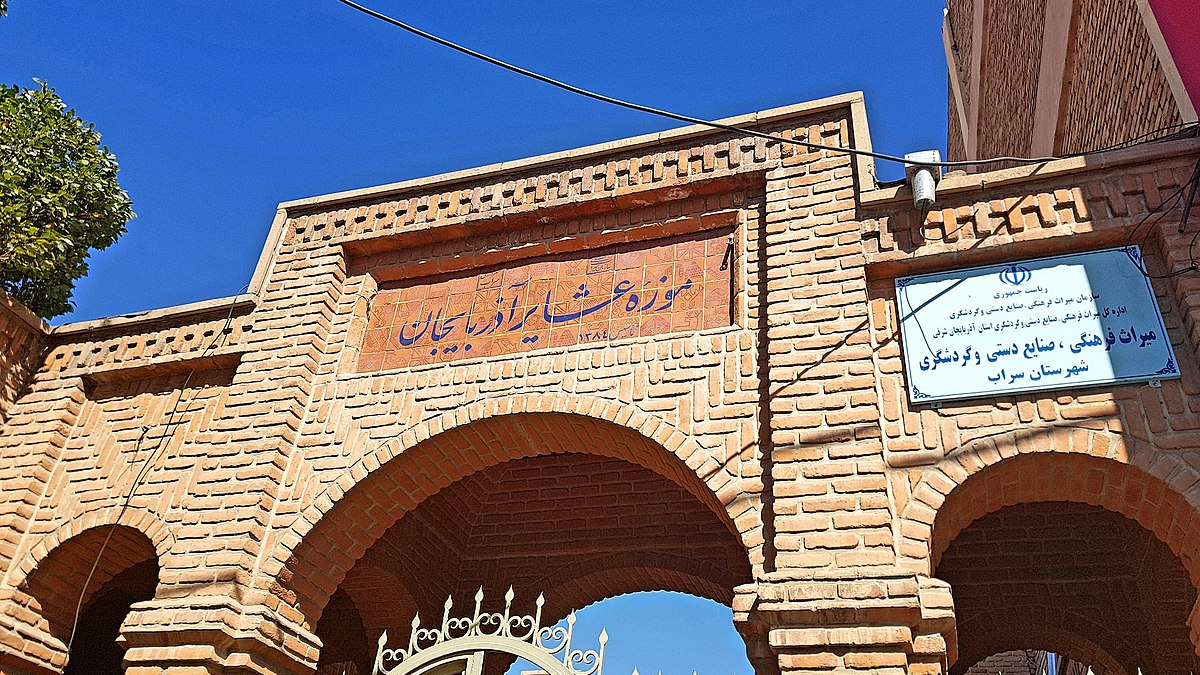

Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art

Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art

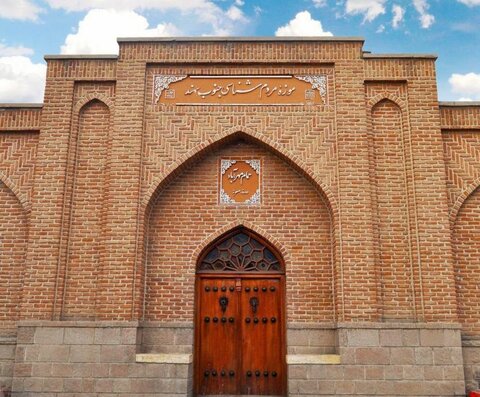

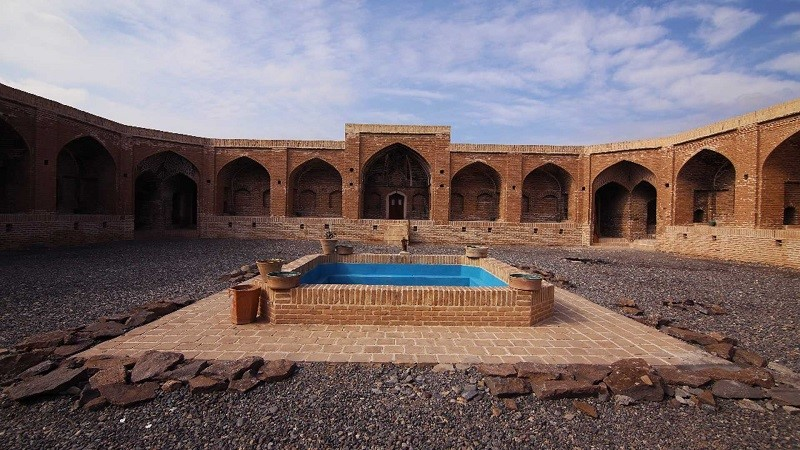

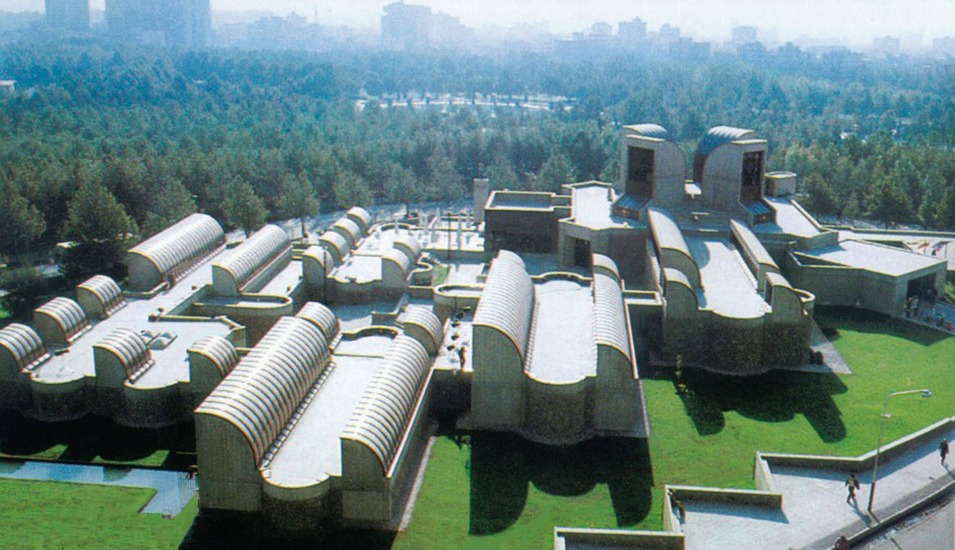

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art is one of the most renowned museums in Iran. It was established in 1977 (22 Mehr 1356 in the Iranian calendar) in the northwestern corner of today’s Laleh Park on North Kargar Street in Tehran. The building was designed by Kamran Diba in a modern architectural style, inspired by the windcatchers of Iran’s desert regions.

The museum houses one of the most comprehensive and important collections of modern art outside Europe and North America, and is considered among the top 5 to 10 neo-modern art collections in the world. Its collection includes major works from movements such as Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, Minimalism, Conceptual Art, and Photorealism. The permanent collection of the museum contains over 3,000 valuable works by masters of visual arts, with nearly 400 considered of exceptional value. Some of the museum’s highlighted works include masterpieces by Gauguin, Renoir, Picasso, Magritte, Ernst, Pollock, Warhol, Léger, and Giacometti. Additionally, the museum possesses a very important and comprehensive collection of modern and contemporary Iranian art, making it a central hub for Iran’s visual arts heritage.

The collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art is considered part of Iran’s public assets, with the total estimated value of its works ranging between $5 to $10 billion. The museum currently operates as one of the units under the Deputy of Artistic Affairs of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance.

The modern and contemporary art movement in Iran began around the 1940s (1320s in the Iranian calendar), following the death of Kamāl-ol-Molk and the opening of the Faculty of Fine Arts at the University of Tehran. With the arrival of Western instructors, such as André Godard, and Iranian art students traveling to Europe to study, Iranian artists gradually became familiar with modern art ideas, including movements like Perceptionism and other contemporary international trends.

The 1320s (1940s in the Gregorian calendar) also witnessed the first modern art exhibitions in Iran, a growing interest in new artistic styles, and the encounter of modernist artists with traditionalists. Pioneering figures such as Mahmoud Javadi-Pour, Hossein Kazemi, and Jalil Zia-Pour played key roles in opening the way for the acceptance of modern art in Iran. Artistic interactions among these artists increased alongside the growth of galleries in Tehran, and the first Iranian art circles—notably the “Rooster” Association (Anjoman-e Khorus-e Jangi)—began their activities, fostering a new cultural and artistic community.

The 1330s (1950s in the Gregorian calendar) saw increased travel of Iranian artists abroad and their exposure to the Minimalist and New York School of Visual Arts. The gradual return of Iranian students from overseas during this decade brought modern artistic ideas to Iran, prompting the first generation of young, prominent artists—including Parviz Tanavoli, Hossein Zenderoudi, and Siah Armajani—to seek a venue to exhibit Iranian artworks. Although the Iranian Biennale took place for five pre-revolution cycles, it was later suspended, and modernist artists began frequenting venues like the Artists’ Club (Bashgah-e Honarmandan). During this period, the government primarily supported traditional Iranian art and works by graduates of the Faculty of Fine Arts. However, with Farah Diba’s marriage to Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, a new faction emerged within the government that backed modernism and contemporary global art. By the mid-1350s (1970s), the activities of the Special Office of the Empress (Farah Pahlavi) had expanded Iran’s cultural connections with international institutions such as UNESCO and the International Council of Museums (ICOM), and led to large-scale acquisitions of contemporary art by government agencies.

After the 1979 Iranian Revolution (1357 Iranian calendar), revolutionaries initially intended to convert the unique building of the museum into a Hosseinieh (religious center), but this plan was not carried out. Nevertheless, unlike many other museums in Iran, the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art experienced only a short closure. According to experts, what happened to the museum during the events leading up to and following the revolution—which coincided with the new Islamic government’s efforts to remove the remnants of the Pahlavi dynasty—was exceptional compared to other similar institutions. Following the February 1979 events, which led to the overthrow of the monarchy, the museum was closed for two weeks. It then continued operating behind closed doors for six months with its main staff, until new artistic institutions were established and management changed, after which the museum reopened to the public. From that point onward, many Western artworks in the museum were labeled “not for display” and hidden from public view. Some works, particularly those depicting nudity, provoked reactions from the officials of the Islamic Republic government. However, in the 1990s (1370s Iranian calendar), a number of these artworks were sent to Western museums for exhibition.

In the early years after the revolution, various exhibitions were held at the museum to commemorate the anniversary of the revolution. These exhibitions featured works by revolutionary artists as well as traditional arts, such as calligraphy and miniature painting. This practice continued for several years until the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art began organizing regular biennial and triennial exhibitions. The first Iranian Painting Biennale was held in autumn 1991 (1370 Iranian calendar, 12 years after the revolution), organized by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance at the museum. According to its catalogs, the aim of the exhibition was to improve the quantity and quality of painting, create a competitive space for artists, and discover and support young talent. Most of the selected works reflected Iranian–Islamic themes, and a section of the exhibition was even titled “Palestine”. During the first biennale, the museum also held a conference focused on “cultural and artistic identity”. Although cultural and artistic identity had been discussed before the revolution, this conference emphasized the revolutionary, Islamic, and traditional aspects of culture, with officials hoping to promote Islamic art. In 1993 (1372 Iranian calendar), the second biennale was held with a slightly less strict focus on purely Islamic art. From that point onward, a separate biennale was dedicated to miniature painting, highlighting this traditional art form.

Up to 15 years after the revolution, the museum had seen nearly 15 different directors, and its focus shifted toward exhibiting modern art serving ideological or political propaganda purposes. According to experts, during this period, the museum had effectively become a gallery for war-related artworks, particularly pieces depicting the Iran–Iraq War, images of the war dead, and works by revolutionary Palestinian and Mexican artists. This era in the history of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art is often referred to as the “Revolutionary Values Period.” Directors during this time were appointed by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, and most lacked formal artistic education or experience.After the 1997 elections (1376 Iranian calendar), the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art became the most important center for visual arts under the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance. From that time, the museum actively and systematically organized seminars, exhibitions, and biennials. Neo-traditionalist artists and some of the key figures of the Saqqakhaneh movement, including Hossein Zenderoudi, Masoud Arabshahi, Mohsen Vaziri-Moghaddam, Mansoureh Hosseini, Behjat Sadr, and Parviz Tanavoli—some of whom had distanced themselves from Iran’s artistic community after the revolution—were now invited to hold exhibitions or participate in seminars, and their works were showcased in the “Pioneers of Modern Iranian Art” series. During this period, the museum also expanded its international activities, organizing exhibitions in Europe, the U.S., and Asia. By exhibiting works in painting, graphic design, and sculpture, the museum broadened its audience, and renowned international Iranian artists such as Abbas Kiarostami, Aydin Aghdashloo, and Farah Osuli held exhibitions alongside younger artists.

Twenty-two years after the revolution, a significant portion of the museum’s Western collection was displayed in several exhibitions over five years, focusing on Pop Art, Impressionism, and Minimalism. In 2005 (approximately 27 years after the revolution), a major exhibition of previously restricted works from the collection was organized exclusively for art specialists. However, some famous pieces—such as Renoir’s Gabriel with Open Shirt and Jasper Johns’ Passage 2—were not included. Additionally, when authorities deemed the middle panel of Francis Bacon’s triptych, Two Figures Lying in Bed in the Presence of Others, as potentially depicting homosexual themes, a formal request was sent to the museum organizer to remove that panel from the display. This exhibition, titled “The Modern Art Movement,” was realized through the efforts of museum officials and with direct support from President Khatami, marking the first time since the revolution that works by Andy Warhol, Vincent van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Salvador Dalí were shown publicly. Sami’ Azar succeeded in convincing government officials to allow the full display of the collection to domestic and international art specialists. The exhibition lasted five months and was very well received. However, after Mahmoud Ahmadinejad came to power, Sami’ Azar resigned, and the artworks were once again stored in the museum’s basement.

With the end of Sami’ Azar’s tenure and a shift in cultural policies, Habibollah Sadeghi, a revolutionary painter, was appointed director of the museum, and ideological trends aligned with the early revolution dominated its programming. After him, Mahmoud Shalouei assumed leadership of the museum. Simultaneously serving as Director General of Visual Arts at the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, he enforced strict regulatory policies on artistic activities. This period was marked by weak and sometimes irrelevant exhibitions in contemporary art, leading to a decline in museum visitors.

In December 2015, the United States returned 14 artworks to Iran by artists such as Peter Eisenman, Michael Graves, and Robert Stern, which had been purchased by the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in 1978, one year before the 1979 Revolution.

Architecture

The building of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art is considered a notable example of modern architecture in Iran. The design incorporates traditional Iranian architectural elements and philosophical concepts alongside modern features. The architect, Kamran Diba, integrated traditional Iranian elements such as hashti (entrance vestibule), chaharsu (cross-shaped central hall), and passageways into the design. According to Diba, there is no comparable museum architecture in any Arab or Muslim country, including Egypt and Turkey. Diba drew inspiration from Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright for the overall design and also looked at the Museum of Modern Art in New York when planning its interior and exhibition spaces. He additionally employed ideas from Josep Lluís Sert, such as the Fondation Maeght, and Louis Kahn, whose works embody a deep sense of mysticism. A number of bronze sculptures by Parviz Tanavoli were commissioned by Diba specifically for the museum and installed around its exterior. Diba designed the museum’s interior spaces to enhance interactions among people and their activities. The open areas and gently curving corridors leading to the galleries effectively create this intended sense of connection.

The museum building is constructed of stone and concrete, and overall—including its surrounding gardens—it covers an area of 8,500 square meters. The total wall surface of the museum measures approximately 2,500 square meters. The museum itself spans more than 5,000 square meters, and its construction took nine years to complete. The museum grounds have two entrances: one, considered a service entrance, opens toward Laleh Park, and the other, the main entrance, faces Kargar Street to the west. The museum building is located at the southern part of the site, while the sculpture garden, a large grassed area, extends to the north of the building.

The exterior of the building is inspired by the windcatchers of the desert-edge regions of Iran. According to Dibā, since he did not have the budget to visit museums around the world, his attention gradually turned to finding a style in local Iranian architecture, and he found the best examples in the mud rooftops and domes of desert cities. The traditional village arches and light wells derived from desert windcatchers act as guides, channeling exterior light into the interior spaces. Although in the past, the windows at the end of these “windcatcher” arches functioned for air circulation and ventilation, today they no longer open and only serve to illuminate the interior. The building is rotated 45 degrees relative to the main street, and apart from four skylights above the entrance, all other light wells face northeast.

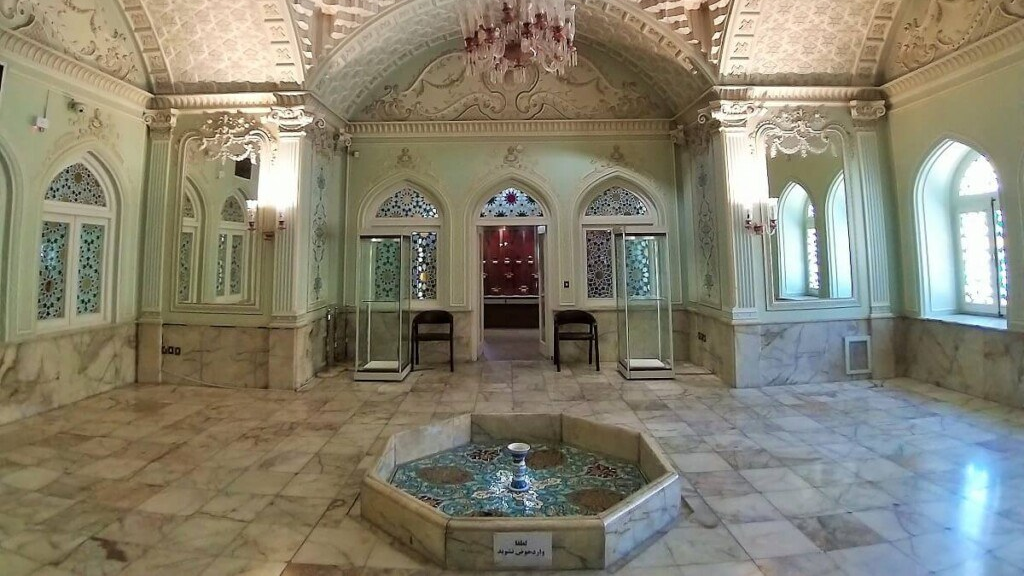

The museum building consists of two main parts: a series of enclosed spaces and a central courtyard. Inside the enclosed area, a spiral pathway is designed, gently sloping downward to guide visitors. This internal spiral contrasts with the exterior facade, giving it a completely modern appearance. The spiral includes seven main spaces or galleries. The first space is the main hall of the building, called Gallery One. This gallery gradually connects to the next gallery, leading visitors downward into the interior. The galleries generally follow similar designs, but Galleries One and Five, which form the main axis of the museum, differ from the others. Each gallery connects to the next via a gentle sloped passage, harmoniously integrated with the gallery layout.

The enclosed spaces are designed so that Gallery One, or the main hall, serves as both the starting and ending point for visitors. This hall is based on a semi-regular octagon with a high vaulted ceiling, and above it sits a large skylight with four windcatchers. In designing this hall, Dība placed great emphasis on the central space and its connections—to the entrance, to the chain of other galleries, and also to the museum’s bookstore and restaurant. The connection between the main hall and the lowest level of the museum is formed through the central void and the slope of the spiral pathway. At the bottom of the spiral, within the hastī (entry vestibule), there is a modern artwork by the Japanese artist Noriyuki Haraguchi titled Matter and Thought. Made in Iran, this piece combines oil and steel and evokes the feeling of traditional Iranian waterhouses (ḥowzkhāneh). Due to the reflective quality of the materials, visitors see it as a large mirror-like surface.

The open spaces and central courtyard of the museum have an irregular shape. The central courtyard stretches along a north–south axis, perpendicular to the museum’s entrance, and its form reflects the protrusions and recesses of the gallery volumes. Galleries One and Five each have a glass door opening onto this courtyard. Since the galleries gradually descend, the courtyard itself has multiple levels, with uneven platforms connected by stairs. At the center of the platforms and stairs lies a square pool, aligned with the main axis of the courtyard.

The walls of the museum building are mostly solid with few openings, creating a fortress-like appearance composed of heavy, compact volumes. The materials used for the façade include orange wind-cut stone and concrete. These wind-cut stones were chosen to give the exterior a solid, traditional, and historical look. The circular sections of the skylights are covered with copper sheets, and the glass at the ends of these skylights is dark-colored. The stone walls are framed with concrete, and the cream-toned concrete combined with the rubble stones gives the building a color and ambiance reminiscent of the mud-brick architecture of Iran’s desert regions.

"The curved towers present in the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art have absolutely no connection to traditional windcatchers. Unfortunately, the museum is a copy; some parts are taken from the Miró Museum in Spain. In my opinion, the curved shape of the building is only for lighting purposes and has nothing to do with wind. Fundamentally, this architecture lacks original innovation to be truly considered Iranian. Even the curved connecting space in the center of the building is copied from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York."

Renovation

On April 29, 2018 (9 Ordibehesht 1397), the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art was closed for major renovation works, with a promised reopening in the summer of the same year. However, due to complexities that emerged after the start of the project, issues related to the security and preservation of the collection, and the COVID-19 pandemic, the renovation process lasted 30 months. The museum reopened to the public in mid-February 2021 (Baham 1399) with a display of part of its collection. The renovation was carried out in two phases: In the first phase, a temporary collection space was created and the collection was moved there. Renovation work included insulating the roof and floor, cleaning sewage wells, upgrading the ventilation system, insulating windows, laminating glass, installing new lighting, and enhancing security systems. In the second phase, infrastructure systems and fire-fighting systems (manual and automated) were updated, and some changes in use increased the collection storage space by 20%. The budget for the renovation was reported as 16.5 billion Iranian Tomans.

Visual Identity Controversy

In the final stages of renovation and restoration, a new visual identity and logo for the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art was designed and introduced by Reza Abedini. The unveiling of this new identity sparked negative reactions from many artists and graphic designers, with many defending the original logo designed by Javad Pouyan, which had both a strong connection to the museum’s architecture and had become an integral part of the museum’s identity over the years. Some critics also pointed out weaknesses in Abedini’s design. Ultimately, after several days of debate, the museum authorities announced that the logo would not change, and the new design was discarded.

Museum Facilities

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art has nine galleries. Three of these galleries are dedicated to exhibiting works by international painters and artists from the museum’s permanent collection, which includes highly valuable pieces by Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, René Magritte, Andy Warhol, and others. The remaining six galleries host temporary and seasonal exhibitions, allowing for a dynamic presentation of artworks. The galleries are arranged sequentially along the visitor pathways, making it easy for visitors to view all the artworks in a smooth and organized manner.

Specialized Library

The specialized library of the museum is located at the end of the sloped pathway leading to the administrative and artistic sections. Its collection includes nearly 5,000 books in Persian and other languages, covering a wide range of art-related topics such as architecture, painting, design, visual communication, photography, cinema, and more. The library uses the Library of Congress (LC) classification system, and access is restricted to registered members. Membership is specifically for art students and researchers. The periodicals section holds domestic and selected foreign cultural and artistic journals related to the museum’s fields of interest. Other specialized facilities of the museum include architecture centers and new media hubs, providing additional resources for research and creative activities.

Ancillary Sections

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art also includes several ancillary sections, notably a cinematheque, a specialized bookstore, and a restaurant. The cinematheque began operations in Mehr 1377 (September–October 1998). Its primary goal is to screen significant works of Iranian and world cinema and to provide critical analysis of the films to enhance the audience’s appreciation and understanding. The cinematheque also hosts discussion sessions, seminars, and opening/closing events for exhibitions. The cinematheque has a fixed seating capacity of 200, and its screen measures 6 × 8 meters, allowing the display of both films and slides. Membership is limited, with new members accepted at the beginning of each year. Members enjoy a one-year access to cinematheque programs, as well as other programs offered by the museum and its specialized library.

Art Collection

The museum’s art collection is divided into three main groups: works in the repository (permanent collection), works displayed in the indoor galleries, and sculptures in the outdoor areas.

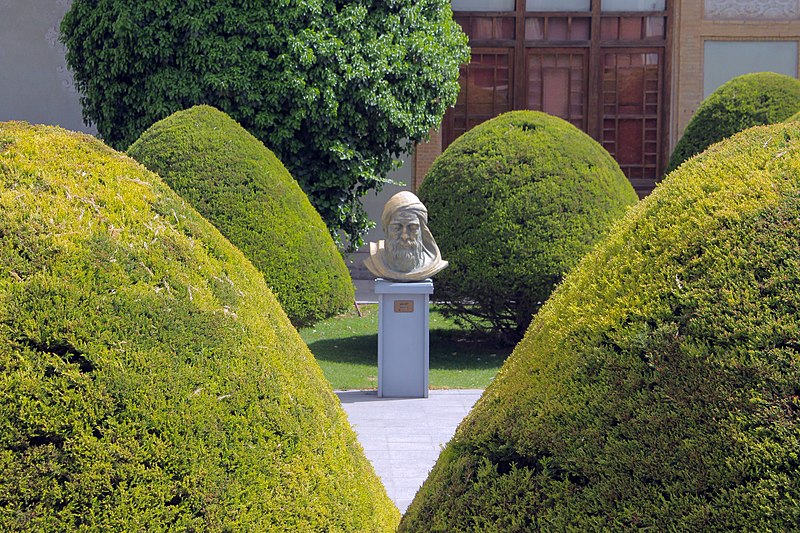

The Sculpture Garden is a green space located north of the museum building. It features works by Max Ernst, Parviz Tanavoli, Henry Moore, Max Bill, and others. During the museum’s construction, Dibā commissioned Tanavoli to create a sculpture called The Passerby for the front entrance. The sculpture depicts a weary man sitting on a bench amidst the outside crowd. Dibā intended the sculpture to connect the people outside with the museum’s interior. Tanavoli based the sculpture’s clothing and face on Dibā himself. The sculpture was confiscated during the revolution and later disappeared.

Some of the sculptures located in the museum grounds include:

Collection

The permanent collection of the museum houses over 3,000 valuable and unique works by leading visual artists from Iran and around the world, nearly 400 of which are considered exceptionally important. In 2004 and 2005, this collection was fully exhibited in a show called The Modern Art Movement. According to the museum director in 2014, most of the works stored in the museum’s basement have not been exposed to outdoor air due to being kept from display, so they have suffered little damage, and none have been seriously harmed. Some art experts consider the works in this collection “unparalleled,” noting that their acquisition reflects the Pahlavi government’s extensive efforts to purchase modern art from the U.S. and Europe to present a progressive image of the regime. Empress Farah Pahlavi, in a 2012 interview with The Guardian, referred to the museum’s works as a “national treasure” and expressed hope that the Iranian people would take good care of the collection.

The Museum of Contemporary Art houses one of the most complete collections of Abstract Expressionism in the world; among the major modern artists, perhaps only Manet, Cézanne, and Mondrian are not represented. According to former museum director Ali-Reza Sami Azar, the museum’s collection is exceptional globally because it encompasses all the artistic movements of the 19th and 20th centuries in one place—a feat unmatched in Japan, the Far East, Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, South America, Asia, or anywhere else. The monetary value of some of these works is so high that they “serve as a backing for Iran’s currency, much like royal jewels.”

In a 2012 report, Fars News Agency assessed the current value of the museum’s artworks. Although these works have never been officially appraised by recognized international experts, their estimated total value exceeds $2.5 billion. Specifically, three pieces that were recently loaned out and required professional appraisal for insurance purposes were valued as follows:

-

Mural on Red Ground, Jackson Pollock – $250 million (estimate by Christie's Foundation)

-

Painter and His Model, Pablo Picasso – $100 million (estimate by foreign official institutions and a group of Iranian experts)

-

Trinidad Fernandez, Kees van Dongen – $60 million (estimate by Dutch experts)

-

No. 2 (Yellow Center) (1954), Mark Rothko – $60–70 million

-

Still Life and Japanese Print, Paul Gauguin – $55 million

Among other works in this museum is the painting Woman III by Willem de Kooning, which in 1994 (1373 SH) was quietly taken out of Iran and swapped with the remaining pages of the Shahnameh of Tahmasbi — which were in the possession of David Geffen, an American billionaire — a trade carried out because the painting was considered “not displayable” in Iran. In 2006 (1385 SH), this painting was sold for $137.5 million, becoming the second most expensive painting sold worldwide at that time. Painter and His Model by Picasso is among the most famous works of this artist and, according to The Guardian, is valued between £25–30 million. The Wall Street Journal also considers it one of Picasso’s finest works. This painting is not displayed publicly in Iran and is kept in the museum’s underground storage opposite a painting of Ruhollah Khomeini.

The works of Andy Warhol in this museum are among his most renowned pieces. Warhol had a good relationship with the royal family and painted portraits of them, including Farah and Ashraf Pahlavi. His painting Suicide (Purple Jumping Man) (1963) was purchased in 1975. Tony Shafrazi, a New York-based art dealer, estimates the current value of the painting at $70 million. Other Warhol works in the museum include paintings of Mao Zedong and portraits of a Native American, Mick Jagger, and Marilyn Monroe.

Among other notable pop art works in the museum is Bratatat (1962), one of Roy Lichtenstein’s most prominent pieces. The museum’s collection also includes more than 10 acrylic and oil works by the Israeli artist Yaacov Agam, which, according to Agam’s son, are among his most valuable pieces. These works were purchased during Farah Pahlavi’s visit to Paris, selected by her personally. Agam, along with his son, traveled to Iran in the summer of 1977, shortly before the museum’s opening, at Farah Pahlavi’s invitation.

Among the works of conceptual sculptors, the museum holds pieces by Donald Judd (Untitled, 1965), Eduardo Chillida (Homage to Pablo Neruda, 1974), Dan Flavin (Untitled, 1966–1971), Sol LeWitt (Cubic Structure, 1976), and Henry Moore (Oval with Points).

Some of the other prominent works in the museum include:

-

Claude Monet; Suburbs of Giverny (1883)

-

Vincent van Gogh; At the Gate of Eternity (lithograph, 1882)

-

Camille Pissarro; Houses at Cernouillet

-

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec; Girl with Accroche-Coeur Hairstyle (1889)

-

James Ensor; Entry of Christ into Brussels in 1889 (etching & watercolor, 1888), The Cathedral, The Marriage of Masks

-

Edvard Munch; Self-Portrait (lithograph)

-

Francis Bacon; Reclining Man with Sculpture (1960–1961)

-

Henri Matisse; The Return from Tahiti (lithograph, 1930)

-

Pablo Picasso; Woman’s Head II, Weeping Woman, Open Window onto Pantheon Street (1920), Monkey and Baby Monkey (sculpture), Jacqueline Reading

-

Marcel Duchamp; For the Large Glass

-

René Magritte; Path of the Sky (1957)

-

Max Ernst; Natural History (1923), Moon Madness (sculpture)

-

Georges Braque; Guitar, Fruit and Pitcher (1927), Five Bronze Pieces (sculpture)

-

Joan Miró; Cave Birds, Bullfighter (color etching, 1969)

-

Alexander Calder; Orange Fish (mobile sculpture, painted metal)

-

David Alfaro Siqueiros; Zapata (lithograph, 1930)

-

Wassily Kandinsky; Bright Extensions (1937)

-

Willem de Kooning; Light in August (formerly with Woman III)

-

Mark Rothko; Orange-Red on Brown, No. 2 (Yellow Center) (1954)

-

Hans Hartung; T973 E13 (1973)

-

Roy Lichtenstein; Melody, Still Life

-

Robert Rauschenberg; Sealing, Framework, Farewell

-

Jasper Johns; Trap, Passage 1, Passage 2 (1966), Gear (lithograph)

The Iranian modern and contemporary art collection of the museum includes a rare compilation of works by pioneers of modern and contemporary Iranian art, which began to be assembled before the revolution and continued afterward, comprising most of the museum’s acquisitions; according to Habibollah Sadeghi—the first director of the museum after the revolution—many of these works were formerly owned by relatives of the previous regime and were confiscated, now making up nearly one-third of the museum’s collection. Among these works are the following:

-

Hossein Zenderoudi; Untitled (Acrylic on Paper, 1962), Untitled (Oil on Canvas, 1967)

-

Sadegh Tabrizi; Two Lovers (1977)

-

Aydin Aghdashloo; Identity: In Praise of Sandro Botticelli (1975)

-

Mansour Qandriz; Untitled (1964)

-

Parviz Tanavoli; Poet and the Nightingale’s Cage (1975)

-

Mohammad Ehsai; Calligraphic Painting (1974)

-

Faramarz Pilaram; Calligraphy (1969)

-

Lili Matin-Daftari; Portrait of Nasrin (1966)

-

Mohsen Vaziri-Moghaddam; Scratches on the Earth (1963)

-

Sohrab Sepehri; Trees (1971)

-

Marko Grigorian; Untitled (1976)

The Museum of Contemporary Art also holds 118 folios from the Shahnameh of Tahmasb, which, although not considered contemporary, came into the museum’s possession due to an exchange in 1994 with one of the museum’s modern works. Some of the illustrations in this collection include:

-

In Praise of God and Wisdom (the opening of the Shahnameh)

-

The snakes of King Zahhak

-

Kaveh casts Zahhak’s court underfoot

-

The sons of Fereydun with the daughters of King Sarv

-

Fereydun receives a letter from Salm and Tur

-

Tur reprimands Qobad

-

Manuchehr kills Salm

-

The birth of Zal

photo collection

The photo collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art includes at least 120 works by foreign photographers such as Henry Fox Talbot, Nadar, August Sander, Alfred Stieglitz, Ansel Adams, Julia Margaret Cameron, Edward Steichen, Lewis Hine, Man Ray, Margaret Bourke-White, and Walker Evans.

The photographs were acquired during Kamran Diba’s management and were exhibited before the revolution in a show called “Creative Photography.” After the revolution, they were not displayed for thirty years until February 2008, when they were shown in an exhibition titled “The Inner Eye.” The oldest photograph in the collection dates back to 1835.

In 2020 (1399 SH), Jamshid Naseri, following the will of his wife Monir Mir’Amadi, donated their art collection—comprising 705 works by contemporary Iranian artists—to the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. This collection includes works by Hossein Zenderoudi, Jazeh Tabatabai, Ghasem Hajizadeh, Ali-Akbar Sadeghi, Mohammad Ehsai, Reza Mafi, Farideh Lashai, and Abbas Kiarostami.

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art collaborates with artists and other contemporary art museums worldwide, engaging in cultural exchanges. These collaborations include organizing periodic exhibitions of foreign artists’ works or lending the museum’s valuable pieces to other cultural institutions. According to Majid Melanorouzi, Director General of the Visual Arts Office at Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, the museum seeks, through such lending programs, to showcase Iranian contemporary art abroad, while ensuring that part of the revenue from ticket sales of these exhibitions overseas returns to the museum. After lending the famous Jackson Pollock painting to Japan, the museum announced its intention to permanently retain that painting and several other unique works in its collection, avoiding future loans of these pieces.

Other collaborations of the museum include lending Trinidad Fernandez’s painting to the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, Netherlands, in 2010, and lending Picasso’s Painter and Model to the Kunsthaus Zürich in October 2010, following a visit and request by Livia Levi-Augusti, the former Swiss ambassador to Iran.

Reflection

The opening of the museum and the acquisition of valuable Western artworks initially drew criticism from some Iranian activists. Leftist groups, such as the Tudeh Party, condemned the purchase of “lowbrow” Western, especially American, art, arguing that during the Cold War, a Picasso painting could not “hold meaning for an Iranian child in the street.” A few Western critics also voiced concerns: for instance, the Herald Tribune criticized the Iranian government’s collection of Western art and suggested focusing on native Iranian art instead. Additionally, Kosie van Brouchen, wife of American sculptor Claes Oldenburg, launched a campaign urging artists not to sell their works to the Iranian monarchy. In 1981 (1360 SH), when many art dealers sought to trade pieces from the museum, Art magazine published an article implying that Iranians were not capable of fully appreciating such a collection, describing it as “an imported device that Iranians do not know how to utilize.”Most of the criticism of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, however, has occurred after the revolution and has focused on the lack of public display of its valuable artworks. These criticisms have come both from art enthusiasts and activists within Iran and from art experts abroad, who have seen the non-exhibition of the works as a sign of Iran’s cultural isolation and of “burying” its artistic heritage. Museum officials, however, have repeatedly explained that the works are not displayed due to limited space for permanent exhibitions and in anticipation of the completion of a building called the “National Museum of Art,” to which the artworks are eventually intended to be transferred.

After the Iranian Revolution, some of the museum’s artworks were not exhibited, and access to the museum’s underground collection was allowed only for a limited number of visits by art experts and students. Following the “Modern Art Movement” exhibition in 2005 (1384), when the full collection was shown to art specialists, some critics questioned the objections of certain government officials regarding the incompatibility of the museum’s works with Islamic norms, noting that only two or three pieces from the entire collection were deemed unexhibitable.

After the revolution, the official museum catalogs also did not mention its founders or its architect, Kamran Diba. Although printed guides refer to the building’s architecture as “unique and excellent,” the omission of Diba’s name in the museum may be due to his familial connection to Iran’s former royal family.

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art has also been criticized for not acquiring notable contemporary works beyond those in its original collection over past decades. Although the museum purchased works by Iranian artists—including miniature painters—after the revolution, some experts believe that these newly acquired works, as presented in exhibitions, have largely lost their “contemporary” character. While a number of foreign artworks were donated to the museum through cultural exchanges, none were purchased, limiting the museum’s connection to global contemporary art. The significant changes in contemporary art worldwide since the post-revolution period, and their absence in displayed or stored works, have led some to argue that the museum has lost the justification for its name, “Museum of Contemporary Art.”

The exchange of Willem de Kooning’s painting Woman III in 1994 (1373 SH) sparked a wave of criticism in Iran. The swap was carried out secretly, without prior announcement, and the news agencies only learned of it after it had taken place. That same year, the Iranian Parliament passed a bill legalizing the sale of artworks from Iranian museums—including the Museum of Contemporary Art—that could not be exhibited domestically. Although this bill was later rejected by the Guardian Council, its timing alongside the Woman III exchange fueled criticism in Iran. Kamran Diba strongly protested the exchange through an article in Kayhan International, warning against the beginning of the museum’s collection being sold. He also objected to the criteria used in the swap between a Western painting and pages from the Iranian Shahnameh, arguing that the assigned values for the two were disproportionate. However, some Iranian art experts supported the exchange; for instance, Aydin Aghdashloo published an article praising the swap, noting that acquiring 118 pages of the valuable Shahnameh of Tahmasp was an achievement that secured “the title deed of Iranian book arts and painting.”

In 2015 (1394 SH), several artworks that had previously been removed from the Museum of Contemporary Art and stored in the warehouse of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance’s Art Department were sold by a property custodian. Following an investigation by the Iranian police, it was revealed that since winter 2014 (1393 SH), he had gradually removed 27 works from the Iranian contemporary art collection, including pieces by Bahman Mohasses, Reza Mafi, Fereydeh Lashai, Hossein Zenderoudi, and Ardeshir Mohasses. However, once the sales were discovered, all the artworks were recovered and returned to the museum’s collection.

Social Impacts

Management changes and the orientation of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, especially after the election of the Khatami government, gave Iranian artists more space to present works inclined toward “the West.” At the 6th Iranian Contemporary Art Biennale in 2002, many works reflected the gap between Iran’s religious government and its artistic community: Unveiled women, a reworked image of the Mona Lisa, and increasing references to Western art in this biennale indicated a striking shift in Iranian society’s post-revolutionary perspective on revolutionary ideals. With the start of the reform era, museum officials made delicate efforts to open up space while not displeasing conservative groups in Iran. Alongside exhibiting works by Western artists and inviting them to Iran, exhibitions of modern Iranian art were also held to prevent criticism from traditionalists that Western artworks were being excessively displayed.

The Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art was able to reintroduce Iranian artists, whose opportunities had been limited due to their affiliations or connections with the previous government, back into society. Among these artists was Parviz Tanavoli, who had been resented by some factions within the Islamic Republic due to his close ties with the Pahlavi court. However, his works were for the first time widely and publicly exhibited after the revolution in the winter of 2003 (1382), as part of a series of exhibitions titled “Pioneers of Modern Iranian Art.” The enthusiastic reception of young people to the Tanavoli exhibition can be seen as the result of the museum’s efforts to reconnect the fragmented generations of Iranian artists.

| Name | Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art |

| Country | Iran |

| State | Tehran |

| City | Tehran |

| Type | Artistic |

| https://www.instagram.com/tehran.moca/ |

_980812202444151.jpg)

_2.jpg)

_980812202444151.jpg)

_2.jpg)

Choose blindless

Red blindless Green blindless Blue blindless Red hard to see Green hard to see Blue hard to see Monochrome Special MonochromeFont size change:

Change word spacing:

Change line height:

Change mouse type:

_crop_1.png)