Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor and the Revival of Nastaliq Script

Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor and the Revival of Nastaliq Script

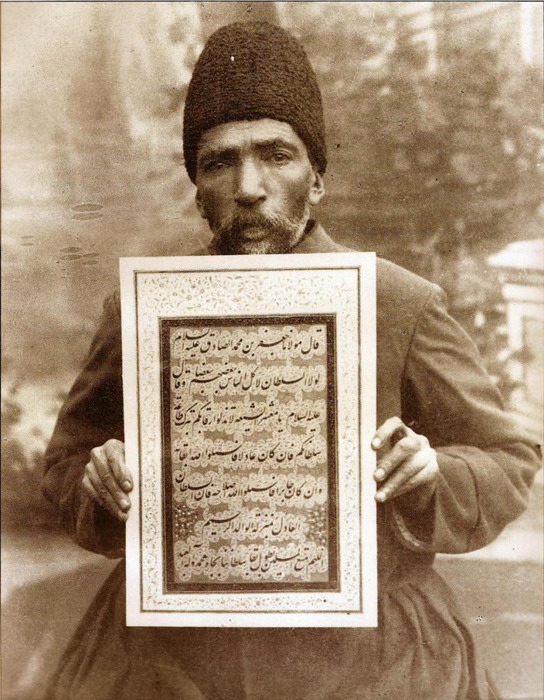

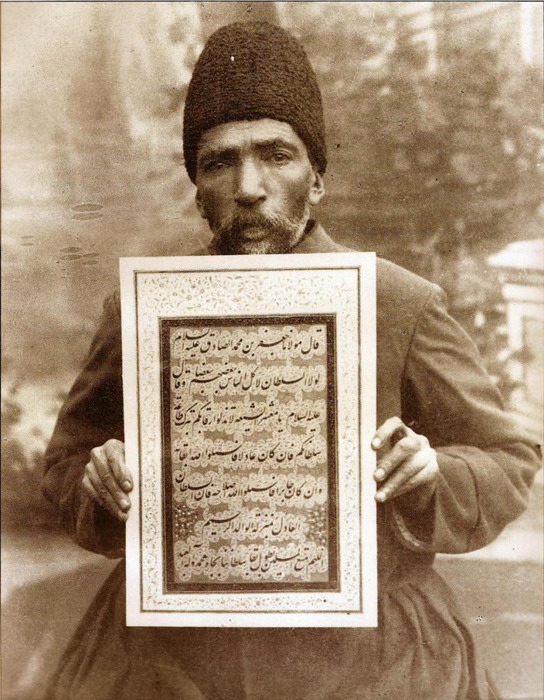

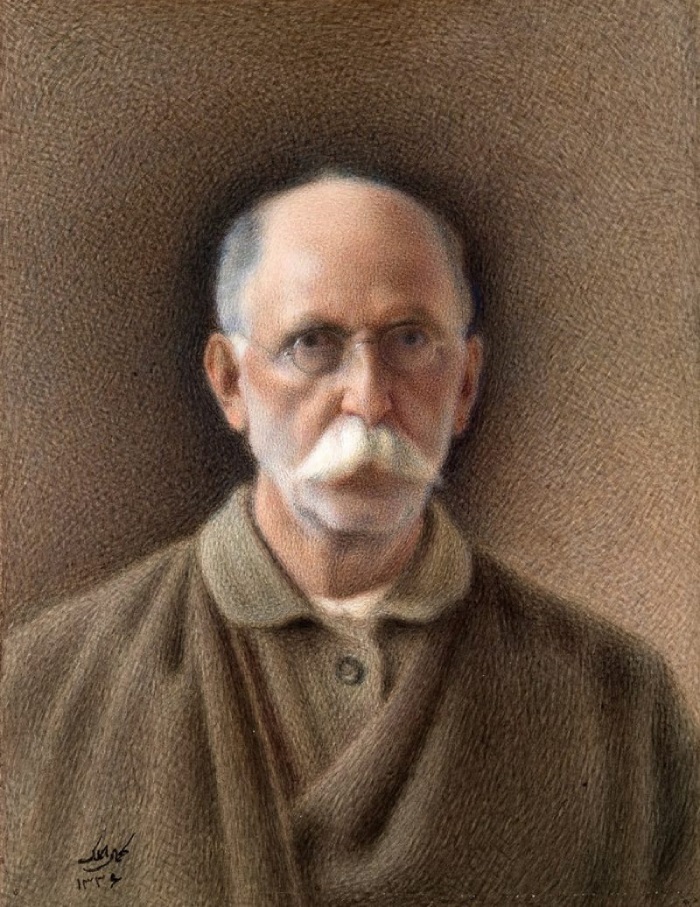

Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor, a renowned master in the field of calligraphy, was born in 1245 AH in the Kalhor tribe of Kermanshah, one of the major tribes settled in the Zagros foothills. His childhood and adolescence were largely devoted to learning martial arts and horseback riding, which resulted in a strong, sturdy, and robust physique. From an early age, the young Mirza showed a profound interest in calligraphy. After migrating to Tehran, he became a student of Mirza Mohammad Khansari, dedicating himself to rigorous practice. From the beginning, he modeled his work on the masterpieces of earlier masters, including Mir Emad, and quickly advanced through the ranks of calligraphic skill. Through his remarkable diligence and perseverance, he eventually surpassed his own teacher. It is said that on some days, Mirza spent up to eighteen hours practicing calligraphy. Dissatisfied with much of his work, he often destroyed it, which is why a significant portion of his surviving manuscripts remains unsigned. Nevertheless, it was not long before Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor became the undisputed master of Nastaʿlīq script of his era, and his fame spread far and wide. So much so that Naser al-Din Shah Qajar summoned him to practice calligraphy in his presence. The Shah also ordered that Mirza work at the Department of Printing (Entebāʿāt). However, since Mirza Mohammad Reza was a man of great ambition, independence, and detachment from worldly matters—dedicated solely to art—he declined the Shah’s proposal. Instead, he agreed only to work under Mohammad Hasan Khan Sanʿi al-Dowleh (Etemad al-Saltaneh) at the Department of Printing whenever he wished and receive his remuneration for it. The only time Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor became officially part of a governmental assignment was in 1300 AH, during Naser al-Din Shah Qajar’s second journey to Khorasan. This was motivated by his deep desire to visit the shrine of Imam Reza. During this trip, a Nastaʿlīq -script newspaper was to be printed lithographically. Etemad al-Saltaneh brought all necessary materials for printing, and the task of writing the original manuscript of the newspaper, named “Ordou-ye Homayoun”, was assigned to Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor. He completed this task with great enthusiasm and skill, producing what is now considered one of the finest surviving examples of his printed calligraphy.

The Advent of Lithography in Iran: A Milestone in the Emergence of Mirza Kalhor’s Genius

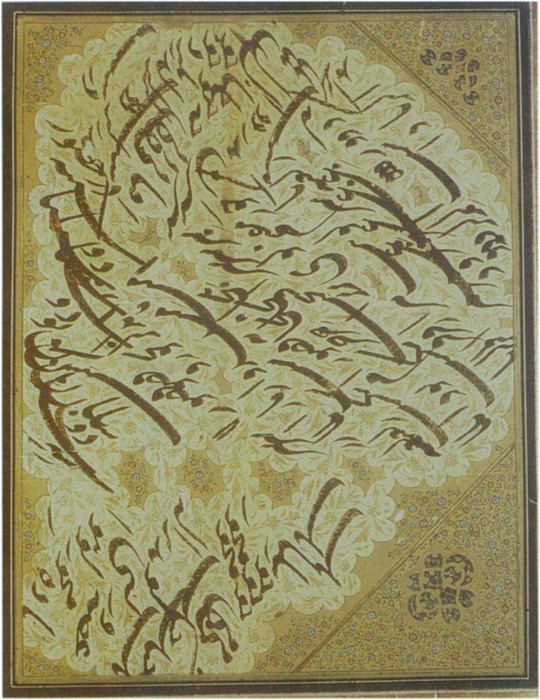

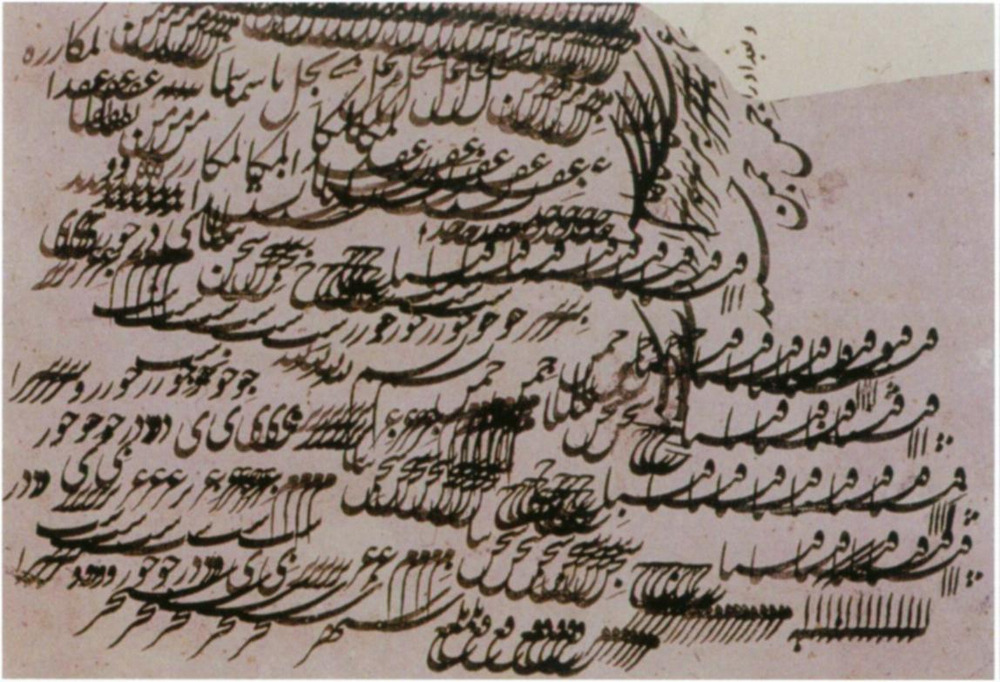

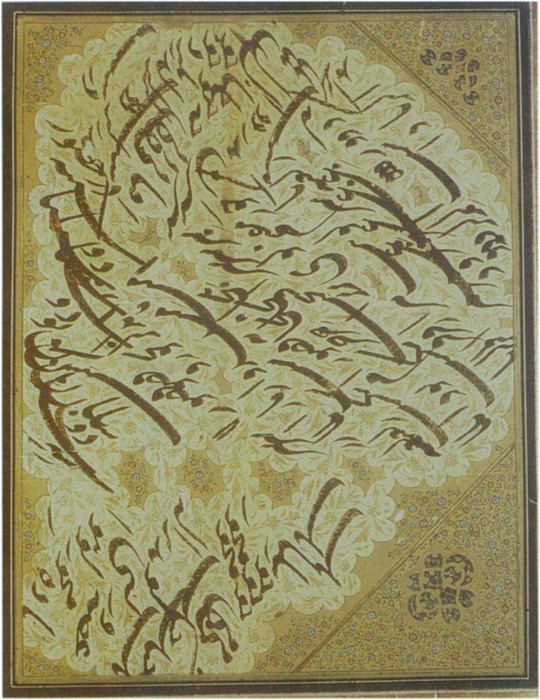

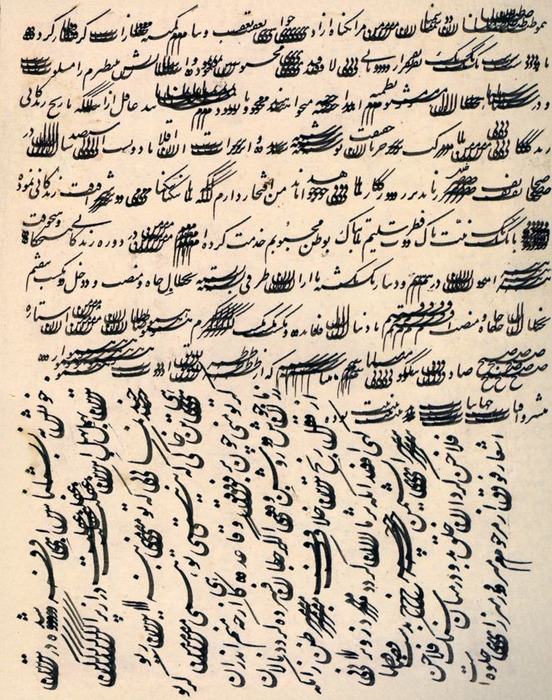

The period of Mirza Mohammad Reza’s calligraphy coincided with a significant and unprecedented development in Iran: the advent of lithographic printing. This major innovation created a fertile ground for the emergence of Mirza Reza’s genius and creativity. As the introduction of printing posed numerous challenges and limitations for reproducing the Nastaʿlīq script, Mirza Kalhor, drawing upon his ingenuity, skill, and innate talent, devised novel solutions to overcome these obstacles. In doing so, he reconciled the flowing elegance of Nastaʿlīq with the technical demands of printing. His adaptation of traditional calligraphy to printing needs led to a new style, now recognized as the school of Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor. He was engaged in stone lithography, preparing designs on the stones for printing, in which the letters appeared bold while the elongated strokes were shortened. Kalhor wrote with such skill that he could form an entire word without lifting the pen from the paper—a technique essential for lithographic printing. Although he was a follower of Mir Emad’s Nastaʿlīq style, he preserved the fundamental principles of the script while introducing subtle, delicate modifications to the traditional method. In doing so, he established his own unique approach, a style that many calligraphers continue to follow today. Throughout his life, Mirza Kalhor trained numerous students, each of whom contributed to the propagation and development of his style. Notable among them were Mirza Zain al-Abidin Qazvini, known as Malik al-Khattatin; Mirza Morteza Najmabadi; Seyyed Morteza Barghani (father of the Mirkhani brothers), Seyyed Mahmoud Sadr al-Kitab; Mirza Abdullah Mostofi, and indirectly, Mohammad Hossein Qazvini, famously known as Emad al-Ketab.

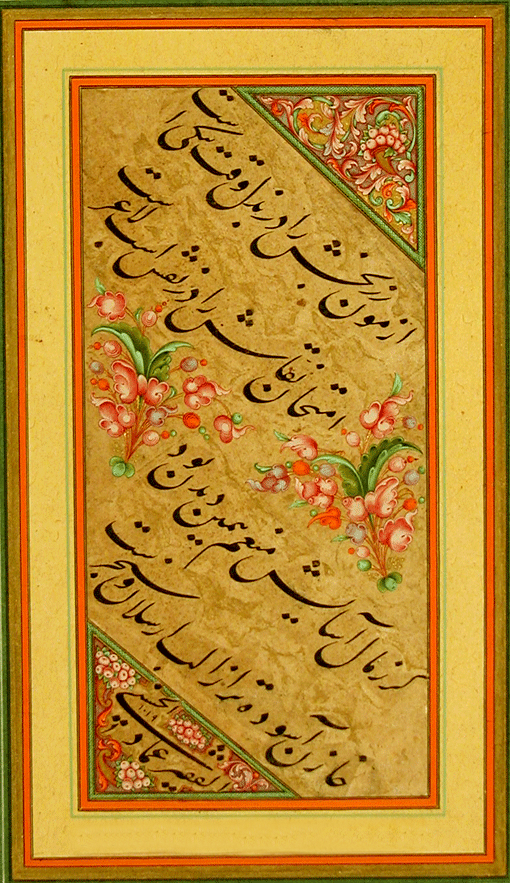

The Style of Mirza Mohammadreza Kalhor

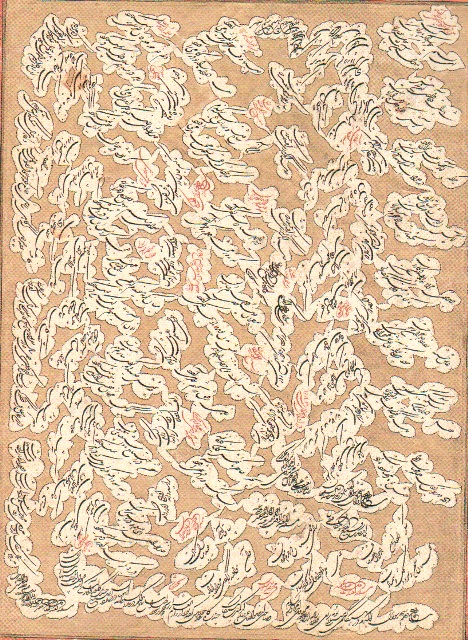

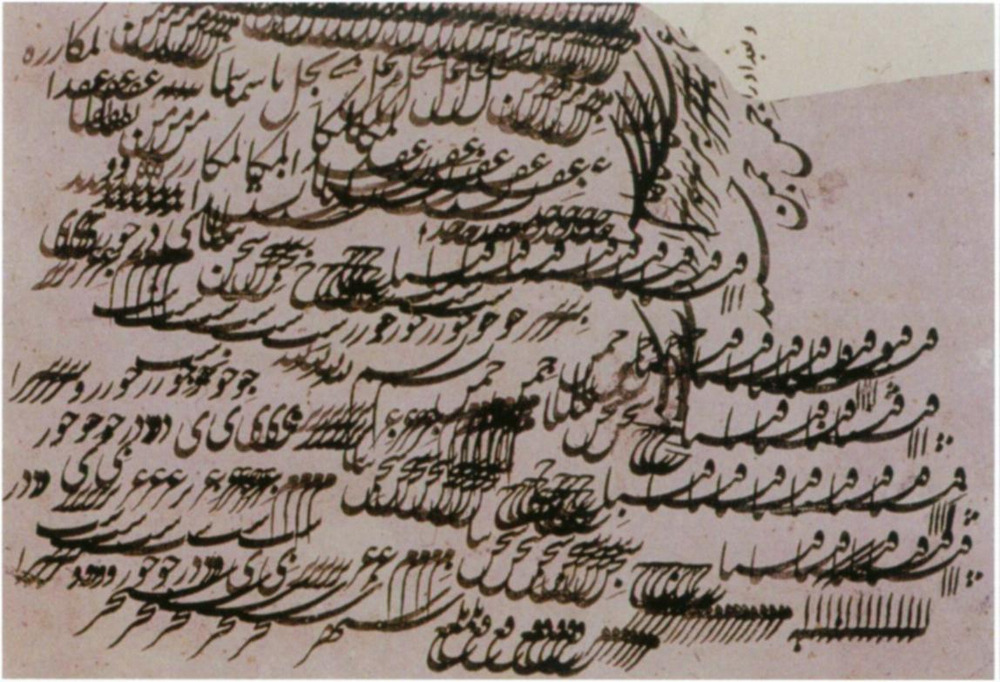

Mirza Kalhor’s distinctive calligraphic style emerged after 1286 AH and became more clearly defined. While adhering to the principles of Mir Emad, he introduced remarkable innovations and noticeable changes in Nastaʿlīq script. The widespread acceptance of this new approach was not easy, as most contemporary calligraphers, who wrote in Mir Emad’s style, opposed Kalhor’s innovations. Nevertheless, he remained undeterred by criticism and mockery, pursuing his novel style with persistence and dedication. Eventually, he refined this approach to a level that it now serves as a model for many Nastaʿlīq calligraphers, marking a significant transformation in the history of Iranian calligraphy. Kalhor emphasized ease and simplicity in writing, transforming the previously rigid order of Nastaʿlīq into a flowing, elegant script. His style became known as “Sahl va Momtanaʿ” (easy yet sophisticated). The method was designed to facilitate and accelerate writing, making it accessible for students and beginners. Its readability and simplicity also contributed to its popularity among the general public, which, given the social context of the time, played a key role in the dissemination and adoption of his style. One of Mirza Kalhor’s distinctive merits, widely recognized by most masters and experts in the field, is his method of cutting and shaping the pen, which likely stems from his intelligence and extensive experience with lithography. Overall, in Mirza Mohammadreza’s style, the script exhibits greater refinement and maturity compared to Mir Emad’s style. Because it was adapted for practical use in newspapers and magazines, additional editorial rules were applied, which both facilitated writing and increased speed. In conclusion, the greatness of Mirza Mohammadreza Kalhor’s personality and his artistic dimensions is undeniable. Throughout his prolific life, he produced what is now considered one of the finest surviving examples. It is noteworthy that in addition to his mastery of Nastaʿlīq, his primary specialty, he also wrote Shikasteh (broken) script beautifully, examples of which can still be seen in Naser al-Din Shah’s decrees and in the margins of the book Makhzan al-Enshah.

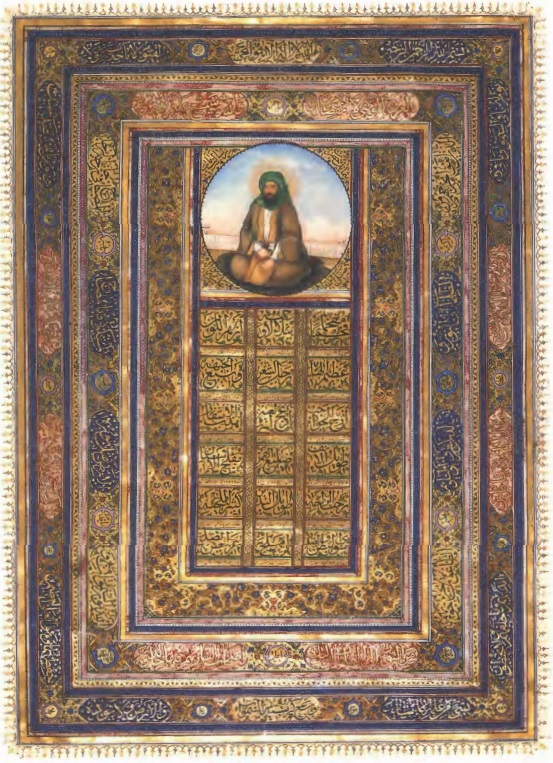

The Astan Quds Razavi Library preserves valuable historical works by Mirza Kalhor in its lithography collection. These works, which are pivotal in tracing the evolution of Nastaʿlīq script during a turbulent period of Mirza’s life, encompass nearly all of the lithographed manuscripts produced by this artist.

Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor finally passed away on Friday, the 25th of Muharram 1310 AH, at the age of 65. Nevertheless, his cohesive and creative style continues to be highly esteemed by calligraphers and remains a dynamic artistic method in the realm of classical Persian calligraphy.

Works of Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor

Among the lasting works of Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor are:Resāleh-ye Ghadiriyeh,Nasāyeh al-Molūk,Munājāt-e Khāja Abdollah Ansārī, the travelogue of Naser al-Din Shah’s second journey to Khorasan, twelve issues of the newspaperOrdū-ye Homāyoun,Makhzan al-Enshah,Feyz al-Domou‘, and others.

| Name | Mirza Mohammad Reza Kalhor and the Revival of Nastaliq Script |

| Country | Iran |

| Type | Calligraphy |

Choose blindless

Red blindless Green blindless Blue blindless Red hard to see Green hard to see Blue hard to see Monochrome Special MonochromeFont size change:

Change word spacing:

Change line height:

Change mouse type:

(7)_1_1.jpg)